Elbow

The elbow is the visible joint between the upper and lower parts of the arm. It includes prominent landmarks such as the olecranon, the elbow pit, the lateral and medial epicondyles, and the elbow joint. The elbow joint[1] is the synovial hinge joint[2] between the humerus in the upper arm and the radius and ulna in the forearm which allows the forearm and hand to be moved towards and away from the body.[3]

| Elbow | |

|---|---|

| |

Anatomy of the elbow (left). | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | articulatio cubiti |

| MeSH | D004550 |

| TA | A01.1.00.023 |

| FMA | 24901 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Medical Subject Headings defines the elbow specifically for humans and other primates,[4] though the term is frequently used for the anterior joints of other mammals, such as dogs.

The name for the elbow in Latin is cubitus, and so the word cubital is used in some elbow-related terms, as in cubital nodes for example.

Structure

Joint

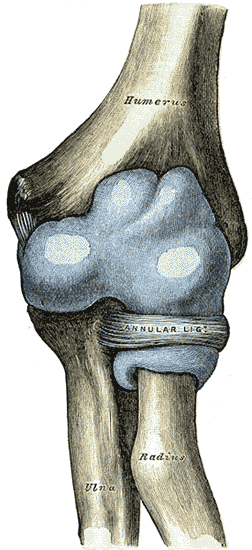

The elbow joint has three different portions surrounded by a common joint capsule. These are joints between the three bones of the elbow, the humerus of the upper arm, and the radius and the ulna of the forearm.

| Joint | From | To | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Humeroulnar joint | trochlear notch of the ulna | trochlea of humerus | Is a simple hinge-joint, and allows for movements of flexion and extension only. |

| Humeroradial joint | head of the radius | capitulum of the humerus | Is a ball-and-socket joint. |

| Proximal radioulnar joint | head of the radius | radial notch of the ulna | In any position of flexion or extension, the radius, carrying the hand with it, can be rotated in it. This movement includes pronation and supination. |

When in anatomical position there are four main bony landmarks of the elbow. At the lower part of the humerus are the medial and lateral epicondyles, on the side closest to the body (medial) and on the side away from the body (lateral) surfaces. The third landmark is the olecranon found at the head of the ulna. These lie on a horizontal line called the Hueter line. When the elbow is flexed, they form an equilateral triangle called the Hueter triangle.[5]

At the surface of the humerus where it faces the joint is the trochlea. The groove running across the trochlea is, in most people, vertical on the anterior side but spirals off on the posterior side. This results in the forearm being aligned to the upper arm during flexion, but forming an angle to the upper arm during extension — an angle known as the carrying angle.[6]

The superior radioulnar joint shares the joint capsule with the elbow joint but plays no functional role at the elbow.[7]

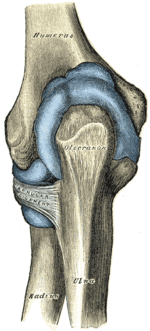

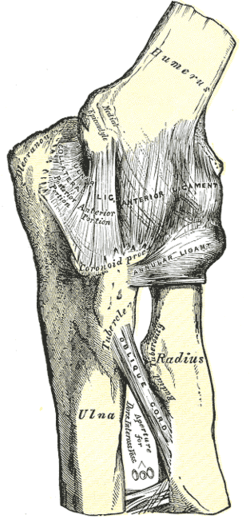

Joint capsule

The elbow joint and the superior radioulnar joint are enclosed by a single fibrous capsule. The capsule is strengthened by ligaments at the sides but relatively weak in front and behind.[8]

On the anterior side the capsule consists mainly of longitudinal fibres. However, some bundles among these fibers run obliquely, thicken and strengthen the capsule, and are referred to as the capsular ligament. Deep fibres of the brachialis muscle insert anteriorly into the capsule and act to pull it and the underlying membrane during flexion in order to prevent them from being pinched.[8]

On the posterior side the capsule is thin and mainly composed of transverse fibres. A few of these fibres stretch across the olecranon fossa without attaching to it and form a transverse band with a free upper border. On the ulnar side, the capsule reaches down to the posterior part of the annular ligament. The posterior capsule is attached to the triceps tendon which prevents the capsule from being pinched during extension.[8]

Synovial membrane

The synovial membrane of the elbow joint is very extensive. On the humerus, it extends up from the articular margins and covers the coronoid and radial fossae anteriorly and the olecranon fossa posteriorly. Distally, it is prolonged down to the neck of the radius and the superior radioulnar joint. It is supported by the quadrate ligament below the annular ligament where it also forms a fold which gives the head of the radius freedom of movement.[8]

Several synovial folds project into the recesses of the joint.[8] These folds or plicae are remnants of normal embryonic development and can be categorized as either anterior (anterior humeral recess) or posterior (olecranon recess).[9] A crescent-shaped fold is commonly present between the head of the radius and the capitulum of the humerus.[8]

On the humerus there are extrasynovial fat pads adjacent to the three articular fossae. These pads fill the radial and coronoid fossa anteriorly during extension, and the olecranon fossa posteriorly during flexion. They are displaced when the fossae are occupied by the bony projections of the ulna and radius.[8]

Ligaments

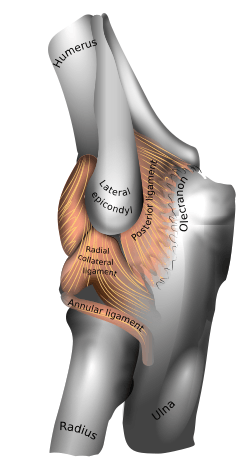

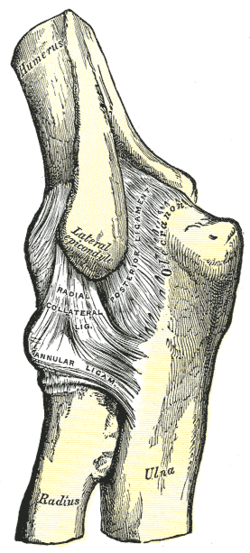

Left: anterior and ulnar collateral ligaments

Right: posterior and radial collateral ligaments

The elbow, like other joints, has ligaments on either side. These are triangular bands which blend with the joint capsule. They are positioned so that they always lie across the transverse joint axis and are, therefore, always relatively tense and impose strict limitations on abduction, adduction, and axial rotation at the elbow.[8]

The ulnar collateral ligament has its apex on the medial epicondyle. Its anterior band stretches from the anterior side of the medial epicondyle to the medial edge of the coronoid process, while the posterior band stretches from posterior side of the medial epicondyle to the medial side of the olecranon. These two bands are separated by a thinner intermediate part and their distal attachments are united by a transverse band below which the synovial membrane protrudes during joint movements. The anterior band is closely associated with the tendon of the superficial flexor muscles of the forearm, even being the origin of flexor digitorum superficialis. The ulnar nerve crosses the intermediate part as it enters the forearm.[8]

The radial collateral ligament is attached to the lateral epicondyle below the common extensor tendon. Less distinct than the ulnar collateral ligament, this ligament blends with the annular ligament of the radius and its margins are attached near the radial notch of the ulna.[8]

Muscles

Flexion

There are three main flexor muscles at the elbow:[10]

- Brachialis acts exclusively as an elbow flexor and is one of the few muscles in the human body with a single function. It originates low on the anterior side of the humerus and is inserted into the tuberosity of the ulna.

- Brachioradialis acts essentially as an elbow flexor but also supinates during extreme pronation and pronates during extreme supination. It originates at the lateral supracondylar ridge distally on the humerus and is inserted distally on the radius at the styloid process.

- Biceps brachii is the main elbow flexor but, as a biarticular muscle, also plays important secondary roles as a stabiliser at the shoulder and as a supinator. It originates on the scapula with two tendons: That of the long head on the supraglenoid tubercle just above the shoulder joint and that of the short head on the coracoid process at the top of the scapula. Its main insertion is at the radial tuberosity on the radius.

Brachialis is the main muscle used when the elbow is flexed slowly. During rapid and forceful flexion all three muscles are brought into action assisted by the superficial forearm flexors originating at the medial side of the elbow.[11] The efficiency of the flexor muscles increases dramatically as the elbow is brought into midflexion (flexed 90°) — biceps reaches its angle of maximum efficiency at 80–90° and brachialis at 100–110°.[10]

Active flexion is limited to 145° by the contact between the anterior muscles of the upper arm and forearm, more so because they are hardened by contraction during flexion. Passive flexion (forearm is pushed against the upper arm with flexors relaxed) is limited to 160° by the bony projections on the radius and ulna as they reach to shallow depressions on the humerus; i.e. the head of radius being pressed against the radial fossa and the coronoid process being pressed against the coronoid fossa. Passive flexion is further limited by tension in the posterior capsular ligament and in triceps brachii.[12]

A small accessory muscle, so called epitrochleoanconeus muscle, may be found on the medial aspect of the elbow running from the medial epicondyle to the olecranon.[13]

Extension

Elbow extension is simply bringing the forearm back to anatomical position.[11] This action is performed by triceps brachii with a negligible assistance from anconeus. Triceps originates with two heads posteriorly on the humerus and with its long head on the scapula just below the shoulder joint. It is inserted posteriorly on the olecranon.[10]

Triceps is maximally efficient with the elbow flexed 20–30°. As the angle of flexion increases, the position of the olecranon approaches the main axis of the humerus which decreases muscle efficiency. In full flexion, however, the triceps tendon is "rolled up" on the olecranon as on a pulley which compensates for the loss of efficiency. Because triceps' long head is biarticular (acts on two joints), its efficiency is also dependent on the position of the shoulder.[10]

Extension is limited by the olecranon reaching the olecranon fossa, tension in the anterior ligament, and resistance in flexor muscles. Forced extension results in a rupture in one of the limiting structures: olecranon fracture, torn capsule and ligaments, and, though the muscles are normally left unaffected, a bruised brachial artery.[12]

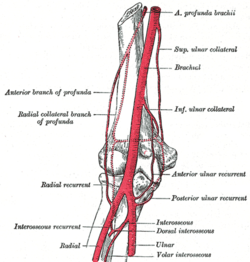

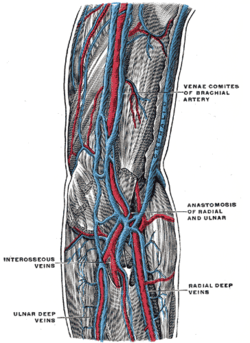

Blood supply

The arteries supplying the joint are derived from an extensive circulatory anastomosis between the brachial artery and its terminal branches. The superior and inferior ulnar collateral branches of the brachial artery and the radial and middle collateral branches of the profunda brachii artery descend from above to reconnect on the joint capsule, where they also connect with the anterior and posterior ulnar recurrent branches of the ulnar artery; the radial recurrent branch of the radial artery; and the interosseous recurrent branch of the common interosseous artery.[14]

The blood is brought back by vessels from the radial, ulnar, and brachial veins. There are two sets of lymphatic nodes at the elbow, normally located above the medial epicondyle — the deep and superficial cubital nodes (also called epitrochlear nodes). The lymphatic drainage at the elbow is through the deep nodes at the bifurcation of the brachial artery, the superficial nodes drain the forearm and the ulnar side of the hand. The efferent lymph vessels from the elbow proceed to the lateral group of axillary lymph nodes.[14][15]

Nerve supply

The elbow is innervated anteriorly by branches from the musculocutaneous, median, and radial nerve, and posteriorly from the ulnar nerve and the branch of the radial nerve to anconeus.[14]

Development

The elbow undergoes dynamic development of ossification centers through infancy and adolescence, with the order of both the appearance and fusion of the apophyseal growth centers being crucial in assessment of the pediatric elbow on radiograph, in order to distinguish a traumatic fracture or apophyseal separation from normal development. The order of appearance can be understood by the mnemonic CRITOE, referring to the capitellum, radial head, internal epicondyle, trochlea, olecranon, and external epicondyle at ages 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 and 11 years. These apophyseal centers then fuse during adolescence, with the internal epicondyle and olecranon fusing last. The ages of fusion are more variable than ossification, but normally occur at 13, 15, 17, 13, 16 and 13 years, respectively.[16] In addition, the presence of a joint effusion can be inferenced by the presence of the fat pad sign, a structure that is normally physiologically present, but pathologic when elevated by fluid, and always pathologic when posterior.[17]

Function

The function of the elbow joint is to extend and flex the arm grasp and reach for objects.[18] The range of movement in the elbow is from 0 degrees of elbow extension to 150 of elbow flexion.[19] Muscles contributing to function are all flexion (biceps brachii, brachialis, and brachioradialis) and extension muscles (triceps and anconeus).

In humans, the main task of the elbow is to properly place the hand in space by shortening and lengthening the upper limb. While the superior radioulnar joint shares joint capsule with the elbow joint, it plays no functional role at the elbow.[7]

With the elbow extended, the long axis of the humerus and that of the ulna coincide. At the same time, the articular surfaces on both bones are located in front of those axes and deviate from them at an angle of 45°. Additionally, the forearm muscles that originate at the elbow are grouped at the sides of the joint in order not to interfere with its movement. The wide angle of flexion at the elbow made possible by this arrangement — almost 180° — allows the bones to be brought almost in parallel to each other.[7]

Carrying angle

When the arm is extended, with the palm facing forward or up, the bones of the upper arm (humerus) and forearm (radius and ulna) are not perfectly aligned. The deviation from a straight line occurs in the direction of the thumb, and is referred to as the "carrying angle" (visible in the right half of the picture, right).

The carrying angle permits the arm to be swung without contacting the hips. Women on average have smaller shoulders and wider hips than men, which tends to produce a larger carrying angle (i.e., larger deviation from a straight line than that in men). There is, however, extensive overlap in the carrying angle between individual men and women, and a sex-bias has not been consistently observed in scientific studies.[20] This could however be attributed to the very small sample sizes in those cited earlier studies. A more recent study based on a sample size of 333 individuals from both sexes concluded that carrying angle is a suitable secondary sexual characteristic.[21]

The angle is greater in the dominant limb than the non-dominant limb of both sexes,[22] suggesting that natural forces acting on the elbow modify the carrying angle. Developmental,[23] aging and possibly racial influences add further to the variability of this parameter.

Pathology

Right: AP X ray of a dislocated right elbow

The types of disease most commonly seen at the elbow are due to injury.

Tendonitis

Two of the most common injuries at the elbow are overuse injuries: tennis elbow and golfer's elbow. Golfer's elbow involves the tendon of the common flexor origin which originates at the medial epicondyle of the humerus (the "inside" of the elbow). Tennis elbow is the equivalent injury, but at the common extensor origin (the lateral epicondyle of the humerus).

Fractures

There are three bones at the elbow joint, and any combination of these bones may be involved in a fracture of the elbow. Patients who are able to fully extend their arm at the elbow are unlikely to have a fracture (98% certainty) and an X-ray is not required as long as an olecranon fracture is ruled out.[24] Acute fractures may not be easily visible on X-ray.

Dislocation

Elbow dislocations constitute 10% to 25% of all injuries to the elbow. The elbow is one of the most commonly dislocated joints in the body, with an average annual incidence of acute dislocation of 6 per 100,000 persons.[26] Among injuries to the upper extremity, dislocation of the elbow is second only to a dislocated shoulder. A full dislocation of the elbow will require expert medical attention to re-align, and recovery can take approximately 8–14 weeks.

Infection

Infection of the elbow joint (septic arthritis) is uncommon. It may occur spontaneously, but may also occur in relation to surgery or infection elsewhere in the body (for example, endocarditis).

Arthritis

Elbow arthritis is usually seen in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis or after fractures that involve the joint itself. When the damage to the joint is severe, fascial arthroplasty or elbow joint replacement may be considered.[27]

Bursitis

Olecranon bursitis, pain in posterior part of elbow, tenderness, warmth, swelling, pain in both flexion and extension, in chronic case extreme flexion is painful

Clinical significance

Elbow pain can occur for a multitude of reasons, including injury, disease, and other conditions. Common conditions include tennis elbow, golfer’s elbow, distal radioulnar joint rheumatoid arthritis, and cubital tunnel syndrome.

Tennis elbow

Tennis elbow is a very common type of overuse injury. It can occur both from chronic repetitive motions of the hand and forearm, and from trauma to the same areas. These repetitions can injure the tendons that connect the extensor supinator muscles (which rotate and extend the forearm) to the olecranon process (also known as “the elbow”). Pain occurs, often radiating from the lateral forearm. Weakness, numbness, and stiffness are also very common, along with tenderness upon touch.[28] A non-invasive treatment for pain management is rest. If achieving rest is an issue, a wrist brace can also be worn. This keeps the wrist in flexion, thereby relieving the extensor muscles and allowing rest. Ice, heat, ultrasound, steroid injections, and compression can also help alleviate pain. After the pain has been reduced, exercise therapy is important to prevent injury in the future. Exercises should be low velocity, and weight should increase progressively.[29] Stretching the flexors and extensors is helpful, as are strengthening exercises. Massage can also be useful, focusing on the extensor trigger points.[30]

Golfer’s elbow

Golfer's elbow is very similar to tennis elbow, but less common. It is caused by overuse and repetitive motions like a golf swing. It can also be caused by trauma. Wrist flexion and pronation (rotating of the forearm) causes irritation to the tendons near the medial epicondyle of the elbow.[31] It can cause pain, stiffness, loss of sensation, and weakness radiating from the inside of the elbow to the fingers. Rest is the primary intervention for this injury. Ice, pain medication, steroid injections, strengthening exercises, and avoiding any aggravating activities can also help. Surgery is a last resort, and rarely used. Exercises should focus on strengthening and stretching the forearm, and utilizing proper form when performing movements.[32]

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic disease that affects joints. It is very common in the wrist, and is most common at the radioulnar joint. It results in pain, stiffness, and deformities. There are many different treatments for rheumatoid arthritis, and there is no one consensus for which methods are best. Most common treatments include wrist splints, surgery, physical and occupational therapy, and antirheumatic medication.[33]

Cubital tunnel syndrome

Cubital tunnel syndrome, more commonly known as ulnar neuropathy, occurs when the ulnar nerve is irritated and becomes inflamed. This can often happen where the ulnar nerve is most superficial, at the elbow. The ulnar nerve passes over the elbow, at the area known as the “funny bone”. Irritation can occur due to constant, repeated stress and pressure at this area, or from a trauma. It can also occur due to bone deformities, and oftentimes from sports.[34] Symptoms include tingling, numbness, and weakness, along with pain. First line pain management techniques include the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory oral medicines. These help to reduce inflammation, pressure, and irritation of the nerve and around the nerve. Other simple fixes include learning more ergonomically friendly habits that can help prevent nerve impingement and irritation in the future. Protective equipment can also be very helpful. Examples of this include a protective elbow pad, and an arm splint. More serious cases often involve surgery, in which the nerve or the surrounding tissue is moved to relieve the pressure. Recovery from surgery can take awhile, but the prognosis is often a good one. Recovery often includes movement restrictions, and range of motion activities, and can last a few months (cubital and radial tunnel syndrome, 2).

Society and culture

The now obsolete length unit ell relates closely to the elbow. This becomes especially visible when considering the Germanic origins of both words, Elle (ell, defined as the length of a male forearm from elbow to fingertips) and Ellbogen (elbow). It is unknown when or why the second "l" was dropped from English usage of the word. The ell as in the English measure could also be taken to come from the letter L, being bent at right angles, as an elbow.[35] The ell as a measure was taken as six handbreadths; three to the elbow and three from the elbow to the shoulder.[36] Another measure was the cubit (from cubital). This was taken to be the length of a man's arm from the elbow to the end of the middle finger.[37]

Other primates

Though the elbow is similarly adapted for stability through a wide range of pronation-supination and flexion-extension in all apes, there are some minor differences. In arboreal apes such as orangutans, the large forearm muscles originating on the epicondyles of the humerus generate significant transverse forces on the elbow joint. The structure to resist these forces is a pronounced keel on the trochlear notch on the ulna, which is more flattened in, for example, humans and gorillas. In knuckle-walkers, on the other hand, the elbow has to deal with large vertical loads passing through extended forearms and the joint is therefore more expanded to provide larger articular surfaces perpendicular to those forces.[38]

Derived traits in catarrhini (apes and Old World monkeys) elbows include the loss of the entepicondylar foramen (a hole in the distal humerus), a non-translatory (rotation-only) humeroulnar joint, and a more robust ulna with a shortened trochlear notch.[39]

The proximal radioulnar joint is similarly derived in higher primates in the location and shape of the radial notch on the ulna; the primitive form being represented by New World monkeys, such as the howler monkey, and by fossil catarrhines, such as Aegyptopithecus. In these taxa, the oval head of the radius lies in front of the ulnar shaft so that the former overlaps the latter by half its width. With this forearm configuration, the ulna supports the radius and maximum stability is achieved when the forearm is fully pronated.[39]

Notes

- "MeSH Browser". meshb.nlm.nih.gov.

- Palastanga & Soames 2012, p. 138

- Kapandji 1982, pp. 74–7

- "MeSH Browser". meshb.nlm.nih.gov.

- Ross & Lamperti 2006, p. 240

- Kapandji 1982, p. 84

- Palastanga & Soames 2012, pp. 127–8

- Palastanga & Soames 2012, pp. 131–2

- Awaya et al. 2001

- Kapandji 1982, pp. 88–91

- Palastanga & Soames 2012, p. 136

- Kapandji 1982, p. 86

- Gervasio, Olga; Zaccone, Claudio (2008). "Surgical Approach to Ulnar Nerve Compression at the Elbow Caused by the Epitrochleoanconeus Muscle and a Prominent Medial Head of the Triceps". Operative Neurosurgery. 62 (suppl_1): 186–193. doi:10.1227/01.neu.0000317392.29551.aa. ISSN 2332-4252. PMID 18424985.

- Palastanga & Soames 2012, p. 133

- "Cubital nodes". Inner Body. Retrieved June 2012. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - Soma, DB (March 2016). "Opening the Black Box: Evaluating the Pediatric Athlete With Elbow Pain". PM&R. 8 (3 Suppl): S101–12. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2016.01.002. PMID 26972259.

- Lee, YJ; Han, D; Koh, YH; Zo, JH; Kim, SH; Kim, DK; Lee, JS; Moon, HJ; Kim, JS; Chun, EJ; Youn, BJ; Lee, CH; Kim, SS (February 2008). "Adult sail sign: radiographic and computed tomographic features". Acta Radiologica (Stockholm, Sweden : 1987). 49 (1): 37–40. doi:10.1080/02841850701675677. PMID 18210313.

- Dimon, T. (2011). The Body of Motion: its Evolution and Design (pp. 39-42). Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

- Thomas, B. P.; Sreekanth, R. (2012). "Distal radioulnar joint injuries". Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 46 (5): 493–504. doi:10.4103/0019-5413.101031. PMC 3491781. PMID 23162140.

- Steel & Tomlinson 1958, pp. 315–7; Van Roy et al. 2005, pp. 1645–56; Zampagni et al. 2008, p. 370

- Ruparelia et al. 2010

- Paraskevas et al. 2004, pp. 19–23; Yilmaz et al. 2005, pp. 1360–3

- Tukenmez et al. 2004, pp. 274–6

- Appelboam et al. 2008

- Earwaker J (1992). "Posttraumatic calcification of the annular ligament of the radius". Skeletal Radiol. 21 (3): 149–54. doi:10.1007/BF00242127. PMID 1604339.

- Blakeney 2010

- Matsen 2012

- Speed, C., Hazleman, B., & Dalton, S. (2006). Fast Facts : Soft Tissue Disorders (2nd Edition). Abingdon, Oxford, GBR: Health Press Limited. Retrieved from http://www.ebrary.com

- MacAuley, D., & Best, T. (Eds.). (2008). Evidence-Based Sports Medicine. Chichester, GBR: John Wiley & Sons. Retrieved from http://www.ebrary.com

- Thomson, B. (2015, January 1). (5) Tennis Elbow Treatment By Trigger Point Massage. Retrieved February 17, 2015, from http://www.easyvigour.net.nz/fitness/hOBP5_TriggerPoint_Tennis_Elbow.htm

- Dhami, S., & Sheikh, A. (2002). At A Glance - Medial Epicondylitis (Golfer's Elbow). Factiva.

- Golfer's elbow. (2012, October 9). Retrieved March 14, 2015, from http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/golfers-elbow/basics/prevention/con-20027964

- Lee, S., & Hausman, M. (2005). Management of the Distal Radioulnar Joint in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Hand Clinics, (21), 577-589.

- Cubital and Radial Tunnel Syndrome: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment. (2014, September 29). Retrieved February 17, 2015, from http://www.webmd.com/pain-management/cubital-radial-tunnel-syndrome

- O.D.E>2nd edition 2005

- O.D.E. 2nd edition 2005,

- O.D.E. 2nd edition 2005

- Drapeau 2008, Abstract

- Richmond et al. 1998, Discussion, p. 267

References

- Appelboam, A; Reuben, A D; Benger, J R; Beech, F; Dutson, J; Haig, S; Higginson, I; Klein, J A; Le Roux, S; Saranga, S S M; Taylor, R; Vickery, J; Powell, R J; Lloyd, G (2008). "Elbow extension test to rule out elbow fracture: multicentre, prospective validation and observational study of diagnostic accuracy in adults and children". BMJ. 337: a2428. doi:10.1136/bmj.a2428. PMC 2600962. PMID 19066257.

- Awaya, Hitomi; Schweitzer, Mark E.; Feng, Sunah A.; Kamishima, Tamotsu; Marone, Phillip J.; Farooki; Shella; Trudell, Debra J.; Haghighi, Parviz; Resnick, Donald L. (December 2001). "Elbow Synovial Fold Syndrome: MR Imaging Findings". American Journal of Roentgenology. 177 (6): 1377–81. doi:10.2214/ajr.177.6.1771377. PMID 11717088.

- Blakeney, W G (January 2010). "Elbow Dislocation". Life in the Fast Lane.

- Drapeau, MS (July 2008). "Articular morphology of the proximal ulna in extant and fossil hominoids and hominins". J Hum Evol. 55 (1): 86–102. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.01.005. PMID 18472143.

- Kapandji, Ibrahim Adalbert (1982). The Physiology of the Joints: Volume One Upper Limb (5th ed.). New York: Churchill Livingstone.

- Matsen, Frederick A. (2012). "Total elbow joint replacement for rheumatoid arthritis: A Patient's Guide" (PDF). UW Medicine.

- Palastanga, Nigel; Soames, Roger (2012). Anatomy and Human Movement: Structure and Function (6th ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 9780702040535.

- Paraskevas, G; Papadopoulos, A; Papaziogas, B; Spanidou, S; Argiriadou, H; Gigis, J (2004). "Study of the carrying angle of the human elbow joint in full extension: a morphometric analysis". Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy. 26 (1): 19–23. doi:10.1007/s00276-003-0185-z. PMID 14648036.

- Richmond, Brian G; Fleagle, John G; Kappelman, John; Swisher, Carl C (1998). "First Hominoid From the Miocene of Ethiopia and the Evolution of the Catarrhine Elbow" (PDF). Am J Phys Anthropol. 105 (3): 257–77. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199803)105:3<257::AID-AJPA1>3.0.CO;2-P. PMID 9545073. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-17.

- Ross, Lawrence M.; Lamperti, Edward D., eds. (2006). Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. Thieme. p. 240. ISBN 978-3131420817.

- Ruparelia, S; Patel, S; Zalawadia, A; Shah, S (2010). "Study Of Carrying Angle And Its Correlation With Various Parameters". NJIRM. 1 (3). ISSN 0975-9840.

- Steel, F; Tomlinson, J (1958). "The 'carrying angle' in man". Journal of Anatomy. 92 (2): 315–7. PMC 1249704. PMID 13525245.

- Tukenmez, M; Demirel, H; Perçin, S; Tezeren, G (2004). "Measurement of the carrying angle of the elbow in 2,000 children at ages six and fourteen years". Acta Orthopaedica et Traumatologica Turcica. 38 (4): 274–6. PMID 15618770.

- Van Roy, P; Baeyens, JP; Fauvart, D; Lanssiers, R; Clarijs, JP (2005). "Arthro-kinematics of the elbow: study of the carrying angle". Ergonomics. 48 (11–14): 1645–56. doi:10.1080/00140130500101361. PMID 16338730.

- Yilmaz, E; Karakurt, L; Belhan, O; Bulut, M; Serin, E; Avci, M (2005). "Variation of carrying angle with age, sex, and special reference to side". Orthopedics. 28 (11): 1360–3. PMID 16295195.

- Zampagni, M; Casino, D; Zaffagnini, S; Visani, AA; Marcacci, M (2008). "Estimating the elbow carrying angle with an electrogoniometer: acquisition of data and reliability of measurements". Orthopedics. 31 (4): 370. doi:10.3928/01477447-20080401-39. PMID 19292279.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Elbows. |

| Look up elbow in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |