Ginkgo biloba

Ginkgo biloba, commonly known as ginkgo or gingko[4] (both pronounced /ˈɡɪŋkoʊ/), also known as the maidenhair tree,[5] is the only living species in the division Ginkgophyta, all others being extinct. It is found in fossils dating back 270 million years. Native to China,[2] the tree is widely cultivated, and was cultivated early in human history. It has various uses in traditional medicine and as a source of food.

| Ginkgo biloba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mature tree | |

Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Ginkgophyta |

| Class: | Ginkgoopsida |

| Order: | Ginkgoales |

| Family: | Ginkgoaceae |

| Genus: | Ginkgo |

| Species: | G. biloba |

| Binomial name | |

| Ginkgo biloba L. | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

Etymology

The genus name Ginkgo is regarded as a misspelling of the Japanese gin kyo, "silver apricot",[6] which is derived from the Chinese 銀杏 used in Chinese herbalism literature such as Shaoxing Bencao (紹興本草) and Compendium of Materia Medica.

Engelbert Kaempfer first introduced the spelling ginkgo in his book Amoenitatum Exoticarum.[7] It is considered that he may have misspelled "Ginkjo" as "Ginkgo". This misspelling was included by Carl Linnaeus in his book Mantissa plantarum II and has become the name of the tree's genus.

Since the spelling may be confusing to pronounce, ginkgo is sometimes purposely misspelled as "gingko".

Description

Ginkgos are large trees, normally reaching a height of 20–35 m (66–115 ft), with some specimens in China being over 50 m (160 ft). The tree has an angular crown and long, somewhat erratic branches, and is usually deep rooted and resistant to wind and snow damage. Young trees are often tall and slender, and sparsely branched; the crown becomes broader as the tree ages. During autumn, the leaves turn a bright yellow, then fall, sometimes within a short space of time (one to 15 days). A combination of resistance to disease, insect-resistant wood and the ability to form aerial roots and sprouts makes ginkgos long-lived, with some specimens claimed to be more than 2,500 years old.

Ginkgo is a relatively shade-intolerant species that (at least in cultivation) grows best in environments that are well-watered and well-drained. The species shows a preference for disturbed sites; in the "semiwild" stands at Tianmu Mountains, many specimens are found along stream banks, rocky slopes, and cliff edges. Accordingly, ginkgo retains a prodigious capacity for vegetative growth. It is capable of sprouting from embedded buds near the base of the trunk (lignotubers, or basal chichi) in response to disturbances, such as soil erosion. Old individuals are also capable of producing aerial roots on the undersides of large branches in response to disturbances such as crown damage; these roots can lead to successful clonal reproduction upon contacting the soil. These strategies are evidently important in the persistence of ginkgo; in a survey of the "semiwild" stands remaining in Tianmushan, 40% of the specimens surveyed were multistemmed, and few saplings were present.[8]:86–87

Phytochemicals

Extracts of ginkgo leaves contain phenolic acids, proanthocyanidins, flavonoid glycosides, such as myricetin, kaempferol, isorhamnetin and quercetin, and the terpene trilactones, ginkgolides and bilobalides.[9][10] The leaves also contain unique ginkgo biflavones, as well as alkylphenols and polyprenols.[10]

Branches

Ginkgo branches grow in length by growth of shoots with regularly spaced leaves, as seen on most trees. From the axils of these leaves, "spur shoots" (also known as short shoots) develop on second-year growth. Short shoots have very short internodes (so they may grow only one or two centimeters in several years) and their leaves are usually unlobed. They are short and knobby, and are arranged regularly on the branches except on first-year growth. Because of the short internodes, leaves appear to be clustered at the tips of short shoots, and reproductive structures are formed only on them (see pictures below – seeds and leaves are visible on short shoots). In ginkgos, as in other plants that possess them, short shoots allow the formation of new leaves in the older parts of the crown. After a number of years, a short shoot may change into a long (ordinary) shoot, or vice versa.

Leaves

The leaves are unique among seed plants, being fan-shaped with veins radiating out into the leaf blade, sometimes bifurcating (splitting), but never anastomosing to form a network.[11] Two veins enter the leaf blade at the base and fork repeatedly in two; this is known as dichotomous venation. The leaves are usually 5–10 cm (2.0–3.9 in), but sometimes up to 15 cm (5.9 in) long. The old popular name "maidenhair tree" is because the leaves resemble some of the pinnae of the maidenhair fern, Adiantum capillus-veneris. Ginkgos are prized for their autumn foliage, which is a deep saffron yellow.

Leaves of long shoots are usually notched or lobed, but only from the outer surface, between the veins. They are borne both on the more rapidly growing branch tips, where they are alternate and spaced out, and also on the short, stubby spur shoots, where they are clustered at the tips. Leaves are green both on the top and bottom[12] and have stomata on both sides.[13]

Reproduction

Ginkgos are dioecious, with separate sexes, some trees being female and others being male. Male plants produce small pollen cones with sporophylls, each bearing two microsporangia spirally arranged around a central axis.

Female plants do not produce cones. Two ovules are formed at the end of a stalk, and after pollination, one or both develop into seeds. The seed is 1.5–2 cm long. Its fleshy outer layer (the sarcotesta) is light yellow-brown, soft, and fruit-like. It is attractive in appearance, but contains butyric acid[14] (also known as butanoic acid) and smells like rancid butter or vomit[15] when fallen. Beneath the sarcotesta is the hard sclerotesta (the "shell" of the seed) and a papery endotesta, with the nucellus surrounding the female gametophyte at the center.[16]

The fertilization of ginkgo seeds occurs via motile sperm, as in cycads, ferns, mosses and algae. The sperm are large (about 70–90 micrometres)[17] and are similar to the sperm of cycads, which are slightly larger. Ginkgo sperm were first discovered by the Japanese botanist Sakugoro Hirase in 1896.[18] The sperm have a complex multi-layered structure, which is a continuous belt of basal bodies that form the base of several thousand flagella which actually have a cilia-like motion. The flagella/cilia apparatus pulls the body of the sperm forwards. The sperm have only a tiny distance to travel to the archegonia, of which there are usually two or three. Two sperm are produced, one of which successfully fertilizes the ovule. Although it is widely held that fertilization of ginkgo seeds occurs just before or after they fall in early autumn,[11][16] embryos ordinarily occur in seeds just before and after they drop from the tree.[19]

Genome

Chinese scientists published a draft genome of Ginkgo biloba in 2016.[20] The tree has a large genome of 10.6 billion DNA nucleobase "letters" (the human genome has three billion) and about 41,840 predicted genes[21] which enable a considerable number of antibacterial and chemical defense mechanisms.[20]

Taxonomy

Carl Linnaeus described the species in 1771, the specific epithet biloba derived from the Latin bis, "two" and loba, "lobed", referring to the shape of the leaves.[22] Two names for the species recognise the botanist Richard Salisbury, a placement by Nelson as Pterophyllus salisburiensis and the earlier Salisburia adiantifolia proposed by James Edward Smith. The epithet of the latter may have been intended to denote a characteristic resembling Adiantum, the genus of maidenhair ferns.[23]

The scientific name Ginkgo is the result of a spelling error that occurred three centuries ago. Kanji typically have multiple pronunciations in Japanese, and the characters 銀杏 used for ginnan can also be pronounced ginkyō. Engelbert Kaempfer, the first Westerner to investigate the species in 1690, wrote down this pronunciation in the notes that he later used for the Amoenitates Exoticae (1712) with the "awkward" spelling "ginkgo".[24] This appears to be a simple error of Kaempfer; taking his spelling of other Japanese words containing the syllable "kyō" into account, a more precise romanization following his writing habits would have been "ginkio" or "ginkjo".[25] Linnaeus, who relied on Kaempfer when dealing with Japanese plants, adopted the spelling given in Kaempfer's "Flora Japonica" (Amoenitates Exoticae, p. 811).

Despite its complicated spelling, which is due to an exceptionally complicated etymology including a transcription error, "ginkgo" is usually pronounced /ˈɡɪŋkoʊ/,[4] which has given rise to the common other spelling "gingko". The spelling pronunciation /ˈɡɪŋkɡoʊ/ is also documented in some dictionaries.[26][27]

Classification

The relationship of ginkgo to other plant groups remains uncertain. It has been placed loosely in the divisions Spermatophyta and Pinophyta, but no consensus has been reached. Since its seeds are not protected by an ovary wall, it can morphologically be considered a gymnosperm. The apricot-like structures produced by female ginkgo trees are technically not fruits, but are seeds that have a shell consisting of a soft and fleshy section (the sarcotesta), and a hard section (the sclerotesta). The sarcotesta has a strong smell that most people find unpleasant.

The ginkgo is classified in its own division, the Ginkgophyta, comprising the single class Ginkgoopsida, order Ginkgoales, family Ginkgoaceae, genus Ginkgo and is the only extant species within this group. It is one of the best-known examples of a living fossil, because Ginkgoales other than G. biloba are not known from the fossil record after the Pliocene.[28][29]

Distribution and habitat

Although Ginkgo biloba and other species of the genus were once widespread throughout the world, its range shrank until by two million years ago, it was restricted to a small area of China.

For centuries, it was thought to be extinct in the wild, but is now known to grow in at least two small areas in Zhejiang province in eastern China, in the Tianmushan Reserve. However, high genetic uniformity exists among ginkgo trees from these areas, arguing against a natural origin of these populations and suggesting the ginkgo trees in these areas may have been planted and preserved by Chinese monks over a period of about 1,000 years.[31] This study demonstrates a greater genetic diversity in Southwestern China populations, supporting glacial refugia in mountains surrounding eastern Tibetan Plateau, where several old-growth candidates for wild populations have been reported.[31][32] Whether native ginkgo populations still exist has not been demonstrated unequivocally, but evidence grows favouring these Southwestern populations as wild, from genetic data but also from history of those territories, with bigger Ginkgo biloba trees being older than surrounding human settlements.[31]

Where it occurs in the wild, it is found infrequently in deciduous forests and valleys on acidic loess (i.e. fine, silty soil) with good drainage. The soil it inhabits is typically in the pH range of 5.0 to 5.5.[33]

In many areas of China, it has been long cultivated, and it is common in the southern third of the country.[33] It has also been commonly cultivated in North America for over 200 years and in Europe for close to 300, but during that time, it has never become significantly naturalized.[34]

Uses

Horticulture

Ginkgos are popular subjects for growing as penjing and bonsai;[35] they can be kept artificially small and tended over centuries. Furthermore, the trees are easy to propagate from seed.

Cooking

The nut-like gametophytes inside the seeds are particularly esteemed in Asia, and are a traditional Chinese food. Ginkgo nuts are used in congee, and are often served at special occasions such as weddings and the Chinese New Year (as part of the vegetarian dish called Buddha's delight). In Chinese culture, they are believed to have health benefits; some also consider them to have aphrodisiac qualities. Japanese cooks add ginkgo seeds (called ginnan) to dishes such as chawanmushi, and cooked seeds are often eaten along with other dishes.

When eaten in large quantities or over a long period, the gametophyte (meat) of the seed can cause poisoning by 4'-O-methylpyridoxine (MPN). MPN is heat-stable and not destroyed by cooking.[36] Studies have demonstrated the convulsions caused by MPN can be prevented or treated successfully with pyridoxine (vitamin B6).

Some people are sensitive to the chemicals in the sarcotesta, the outer fleshy coating. These people should handle the seeds with care when preparing the seeds for consumption, wearing disposable gloves. The symptoms are allergic contact dermatitis[37][38] or blisters similar to that caused by contact with poison ivy.

Traditional medicine

The first use as a medicine is recorded in the late 15th century in China; among western countries, its first registered medicinal use was in Germany in 1965. Despite use, controlled studies do not support the extract's efficacy for most of the indicated conditions.[39]

Dietary supplement

Although extracts of Ginkgo biloba leaf sold as dietary supplements may be marketed as being beneficial for cognitive function,[40] there is no evidence for effects on memory or attention in healthy people.[41][42] Gingko extract has also been studied in Alzheimer's disease, but there is no good evidence that it has any effect.[42][43][44]

Systematic reviews have shown there is no evidence for effectiveness of ginkgo in treating high blood pressure,[45] menopause-related cognitive decline,[46] tinnitus,[47] post-stroke recovery,[48] peripheral arterial disease,[49] macular degeneration,[50] or altitude sickness.[51][52]

Adverse effects

The use of Ginkgo biloba leaf extracts may have undesirable effects, especially for individuals with blood circulation disorders and those taking anticoagulants, such as aspirin or warfarin, although studies have found ginkgo has little or no effect on the anticoagulant properties or pharmacodynamics of warfarin in healthy subjects.[53][54] Additional side effects include increased risk of bleeding, gastrointestinal discomfort, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, dizziness, heart palpitations, and restlessness.[54][55][56]

According to a systemic review, the effects of ginkgo on pregnant women may include increased bleeding time, and it should be avoided during lactation because of inadequate safety evidence.[57]

Ginkgo biloba leaves and sarcotesta also contain ginkgolic acids,[58] which are highly allergenic, long-chain alkylphenols such as bilobol or adipostatin A[59] (bilobol is a substance related to anacardic acid from cashew nut shells and urushiols present in poison ivy and other Toxicodendron spp.)[38] Individuals with a history of strong allergic reactions to poison ivy, mangoes, cashews and other alkylphenol-producing plants are more likely to experience allergic reaction when consuming non-standardized ginkgo-containing preparations, combinations, or extracts thereof. The level of these allergens in standardized pharmaceutical preparations from Ginkgo biloba was restricted to 5 ppm by the Commission E of the former Federal German Health Authority. Overconsumption of seeds from Gingko biloba can deplete vitamin B6.[60][61]

History

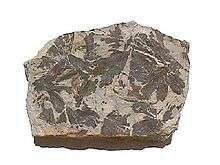

The ginkgo is a living fossil, with fossils recognisably related to modern ginkgo from the Permian, dating back 270 million years. The most plausible ancestral group for the order Ginkgoales is the Pteridospermatophyta, also known as the "seed ferns"; specifically the order Peltaspermales. The closest living relatives of the clade are the cycads,[8]:84 which share with the extant G. biloba the characteristic of motile sperm.

Fossil plants with leaves that have more than four veins per segment have customarily been assigned to the taxon Ginkgo, while the taxon Baiera is used to classify those with fewer than four veins per segment. Sphenobaiera has been used for plants with a broadly wedge-shaped leaf that lacks a distinct leaf stem.

Rise and decline

Fossils attributable to the genus Ginkgo first appeared in the Early Jurassic. One of the earliest fossils ascribed to the Ginkgophyta is Trichopitys, distinguished by having multiple-forked leaves with cylindrical (not flattened), thread-like ultimate divisions. The genus Ginkgo diversified and spread throughout Laurasia during the middle Jurassic and Early Cretaceous.

The Ginkgophyta declined in diversity as the Cretaceous progressed, and by the Paleocene, Ginkgo adiantoides was the only Ginkgo species left in the Northern Hemisphere, while a markedly different (and poorly documented) form persisted in the Southern Hemisphere. Along with that of ferns, cycads, and cycadeoids, the species diversity in the genus Ginkgo drops through the Cretaceous, at the same time the flowering plants were on the rise; this supports the hypothesis that, over time, flowering plants with better adaptations to disturbance displaced Ginkgo and its associates.[8]:93

At the end of the Pliocene, Ginkgo fossils disappeared from the fossil record everywhere except in a small area of central China, where the modern species survived.

Limited number of species

It is doubtful whether the Northern Hemisphere fossil species of Ginkgo can be reliably distinguished. Given the slow pace of evolution and morphological similarity between members of the genus, there may have been only one or two species existing in the Northern Hemisphere through the entirety of the Cenozoic: present-day G. biloba (including G. adiantoides) and G. gardneri from the Paleocene of Scotland.[8]:85

At least morphologically, G. gardneri and the Southern Hemisphere species are the only known post-Jurassic taxa that can be unequivocally recognised. The remainder may have been ecotypes or subspecies. The implications would be that G. biloba had occurred over an extremely wide range, had remarkable genetic flexibility and, though evolving genetically, never showed much speciation.

While it may seem improbable that a single species may exist as a contiguous entity for many millions of years, many of the ginkgo's life-history parameters fit: Extreme longevity; slow reproduction rate; (in Cenozoic and later times) a wide, apparently contiguous, but steadily contracting distribution; and (as far as can be demonstrated from the fossil record) extreme ecological conservatism (restriction to disturbed streamside environments).[8]:91

Adaptation to a single environment

Given the slow rate of evolution of the genus, Ginkgo possibly represents a pre-angiosperm strategy for survival in disturbed streamside environments. Ginkgo evolved in an era before flowering plants, when ferns, cycads, and cycadeoids dominated disturbed streamside environments, forming low, open, shrubby canopies. Ginkgo's large seeds and habit of "bolting" – growing to a height of 10 meters before elongating its side branches – may be adaptions to such an environment.

Modern-day G. biloba grows best in environments that are well-watered and drained,[8]:87 and the extremely similar fossil Ginkgo favored similar environments: The sediment record at the majority of fossil Ginkgo localities indicates it grew primarily in disturbed environments, along streams and levees.[8] Ginkgo, therefore, presents an "ecological paradox" because while it possesses some favorable traits for living in disturbed environments (clonal reproduction) many of its other life-history traits are the opposite of those exhibited by modern plants that thrive in disturbed settings (slow growth, large seed size, late reproductive maturity).[8]:92

Naming

The older Chinese name for this plant is 銀果, meaning "silver fruit", pronounced yínguǒ in Mandarin or Ngan-gwo in Cantonese. The most usual names today are 白果 (bái guǒ), meaning "white fruit", and 銀杏 (yínxìng), meaning "silver apricot". The name 銀杏 was borrowed in Japanese ぎんなん (ginnan) and Korean 은행 (eunhaeng), when the tree was introduced from China.

Cultivation

Ginkgo has long been cultivated in China; some planted trees at temples are believed to be over 1,500 years old. The first record of Europeans encountering it is in 1690 in Japanese temple gardens, where the tree was seen by the German botanist Engelbert Kaempfer. Because of its status in Buddhism and Confucianism, the ginkgo is also widely planted in Korea and parts of Japan; in both areas, some naturalization has occurred, with ginkgos seeding into natural forests.

In some areas, most intentionally planted ginkgos are male cultivars grafted onto plants propagated from seed, because the male trees will not produce the malodorous seeds. The popular cultivar ‘Autumn Gold’ is a clone of a male plant.

The disadvantage of male Ginkgo biloba trees is that they are highly allergenic. They have an OPALS allergy scale rating of 7 (out of 10), whereas female trees, which can produce no pollen, have an OPALS allergy scale rating of 2.[62]

Female cultivars include ‘Liberty Splendor’, ‘Santa Cruz’, and ‘Golden Girl’, the latter so named because of the striking yellow color of its leaves in the fall; all female cultivars release zero pollen.[62]

Many cultivars are listed in the literature in the UK, of which the compact ‘Troll’ has gained the Royal Horticultural Society’s Award of Garden Merit.[63][64]

Ginkgos adapt well to the urban environment, tolerating pollution and confined soil spaces.[65] They rarely suffer disease problems, even in urban conditions, and are attacked by few insects.[66][67]

Society and culture

The ginkgo leaf is the symbol of the Urasenke school of Japanese tea ceremony. The tree is the official tree of the Japanese capital of Tokyo, and the symbol of Tokyo is a ginkgo leaf. The logo of Osaka University has been a simplified ginkgo leaf since 1991 when designer Ikko Tanaka created it for the university's sixtieth anniversary.[68]

Hiroshima

Extreme examples of the ginkgo's tenacity may be seen in Hiroshima, Japan, where six trees growing between 1–2 kilometres (0.62–1.24 mi) from the 1945 atom bomb explosion were among the few living things in the area to survive the blast. Although almost all other plants (and animals) in the area were killed, the ginkgos, though charred, survived and were soon healthy again, among other hibakujumoku (trees that survived the blast).

The six trees are still alive: They are marked with signs at Housenbou (報専坊) temple (planted in 1850), Shukkei-en (planted about 1740), Jōsei-ji (planted 1900), at the former site of Senda Elementary School near Miyukibashi, at the Myōjōin temple, and an Edo period-cutting at Anraku-ji temple.[69]

1000-year-old ginkgo at Tsurugaoka Hachimangū

The ginkgo tree that had stood next to Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū's stone stairway approximately from the Shinto shrine's foundation in 1063, and which appears in almost every old depiction of the shrine, was completely uprooted and irreparably damaged on March 10, 2010.[70] According to an expert who analyzed the tree, the fall was likely due to rot.

Later, both the stump of the severed tree and a replanted section of the trunk sprouted leaves. The shrine is in the city of Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

The tree was nicknamed kakure-ichō (hiding ginkgo), deriving from an Edo period urban legend which told of the assassination of Minamoto no Sanetomo by his nephew, Kugyō, who had been hiding behind the tree.[70]

Gallery

Trunk bark

Trunk bark- Ginkgo pollen-bearing cones

Bud in spring

Bud in spring Ovules ready for fertilization

Ovules ready for fertilization Female gametophyte, dissected from a seed freshly shed from the tree, containing a well-developed embryo

Female gametophyte, dissected from a seed freshly shed from the tree, containing a well-developed embryo Immature ginkgo ovules and leaves

Immature ginkgo ovules and leaves Autumn leaves and fallen seeds

Autumn leaves and fallen seeds A forest of saplings sprout among last year's seeds

A forest of saplings sprout among last year's seeds Ginkgo tree in autumn

Ginkgo tree in autumn- Seeds on tree

Ginkgo biloba leaves

Ginkgo biloba leaves

See also

References

- Mustoe, G.E. (2002). "Eocene Ginkgo leaf fossils from the Pacific Northwest". Canadian Journal of Botany. 80 (10): 1078–1087. doi:10.1139/b02-097.

- "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- "Ginkgo biloba", World Checklist of Selected Plant Families, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, retrieved 8 June 2017

- Company, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing. "The American Heritage Dictionary entry: ginkgo". www.ahdictionary.com.

- "Ginkgo biloba". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- Coombes, Allen J. (1994), Dictionary of Plant Names, London: Hamlyn Books, ISBN 978-0-600-58187-1

- Wolfgang Michel (2011) [2005], On Engelbert Kaempfer's "Ginkgo" (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016

- Royer, Dana L.; Hickey, Leo J.; Wing, Scott L. (2003). "Ecological conservatism in the 'living fossil' Ginkgo". Paleobiology. 29 (1): 84–104. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2003)029<0084:ECITLF>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0094-8373.

- van Beek TA (2002). "Chemical analysis of Ginkgo biloba leaves and extracts". Journal of Chromatography A. 967 (1): 21–55. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(02)00172-3. PMID 12219929.

- van Beek TA, Montoro P (2009). "Chemical analysis and quality control of Ginkgo biloba leaves, extracts, and phytopharmaceuticals". J Chromatogr A. 1216 (11): 2002–2032. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2009.01.013. PMID 19195661.

- "More on Morphology of the Ginkgoales". www.ucmp.berkeley.edu.

- "Ginkgo Tree". www.bio.brandeis.edu. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- "Ginkgo Tree". prezi.com. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- Raven, Peter H.; Ray F. Evert; Susan E. Eichhorn (2005). Biology of Plants (7th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. pp. 429–430. ISBN 978-0-7167-1007-3.

- Plotnik, Arthur (2000). The Urban Tree Book: An Uncommon Field Guide for City and Town (1st ed.). New York: Three Rivers Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-8129-3103-7.

- Laboratory IX – Ginkgo, Cordaites, and the Conifers

- Vanbeek, A. (2000). Ginkgo Biloba (Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: Industrial Profiles). CRC Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-90-5702-488-7.

- Ogura, Y. (1967). "History of Discovery of Spermatozoids In Ginkgo biloba and Cycas revoluta". Phytomorphology. 17: 109–114. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015.

- Holt, B. F.; Rothwell, G. W. (1997). "Is Ginkgo biloba (Ginkgoaceae) Really an Oviparous Plant?". American Journal of Botany. 84 (6): 870–872. doi:10.2307/2445823. JSTOR 2445823.

- Guan, Rui; Zhao, Yunpeng; Zhang, He; Fan, Guangyi; Liu, Xin; Zhou, Wenbin; Shi, Chengcheng; Wang, Jiahao; Liu, Weiqing (1 January 2016). "Draft genome of the living fossil Ginkgo biloba". GigaScience. 5 (1): 49. doi:10.1186/s13742-016-0154-1. ISSN 2047-217X. PMC 5118899. PMID 27871309.

- "Ginkgo 'living fossil' genome decoded". BBC News. 21 November 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- Simpson DP (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5 ed.). London: Cassell Ltd. p. 883. ISBN 978-0-304-52257-6.

- Chandler, Brian (2000). "Ginkgo – origins". Ginkgo pages. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Engelbert Kaempfer (1721). Amoenitates exoticae politico-physico-medicae (in Latin). Lengoviae: Meyer.

- Michel, Wolfgang (2011) [2005]. "On Engelbert Kaempfer's 'Ginkgo'" (PDF). Kyushu University. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "ginkgo". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press.

- "Ginkgo". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- Zhou, Zhiyan; Zheng, Shaolin (2003). "Palaeobiology: The missing link in Ginkgo evolution". Nature. 423 (6942): 821–822. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..821Z. doi:10.1038/423821a. PMID 12815417.

- Julie Jalalpour; Matt Malkin; Peter Poon; Liz Rehrmann; Jerry Yu (1997). "Ginkgoales: Fossil Record". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- Approximate reconstructions by B. M. Begović Bego and Z. Zhou, 2010/2011. Source: B.M. Begović Bego, (2011). Nature's Miracle Ginkgo biloba, Book 1, Vols. 1–2, pp. 60–61.

- Shen, L; Chen, X-Y; Zhang, X; Li, Y-Y; Fu, C-X; Qiu, Y-X (2004). "Genetic variation of Ginkgo biloba L. (Ginkgoaceae) based on cpDNA PCR-RFLPs: inference of glacial refugia". Heredity. 94 (4): 396–401. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800616. PMID 15536482.

- Tang, CQ; al, et (2012). "Evidence for the persistence of wild Ginkgo biloba (Ginkgoaceae) populations in the Dalou Mountains, southwestern China". American Journal of Botany. 99 (8): 1408–1414. doi:10.3732/ajb.1200168. PMID 22847538.

- Fu, Liguo; Li, Nan; Mill, Robert R. (1999). "Ginkgo biloba". In Wu, Z. Y.; Raven, P.H.; Hong, D.Y. (ed.). Flora of China. 4. Beijing: Science Press; St. Louis: Missouri Botanical Garden Press. p. 8.

- Whetstone, R. David (2006). "Ginkgo biloba". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993+ (ed.). Flora of North America. 2. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- D'Cruz, Mark. "Ma-Ke Bonsai Care Guide for Ginkgo biloba". Ma-Ke Bonsai. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- Kajiyama, Y.; Fujii, K.; Takeuchi, H.; Manabe, Y. (2 February 2002). "Ginkgo seed poisoning". Pediatrics. 109 (2): 325–327. doi:10.1542/peds.109.2.325. PMID 11826216.

- Lepoittevin, J. -P.; Benezra, C.; Asakawa, Y. (1989). "Allergic contact dermatitis to Ginkgo biloba L.: relationship with urushiol". Archives of Dermatological Research. 281 (4): 227–30. doi:10.1007/BF00431055. PMID 2774654.

- Schötz, Karl (2004). "Quantification of allergenic urushiols in extracts ofGinkgo biloba leaves, in simple one-step extracts and refined manufactured material(EGb 761)". Phytochemical Analysis. 15 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1002/pca.733. PMID 14979519.

- Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products. "Assessment report on Ginkgo biloba L., folium" (PDF). European Medicines Agency.

- Tewari, D.; Stankiewicz, A. M.; Mocan, A.; Sah, A. N.; Tzvetkov, N. T.; Huminiecki, L.; Horbańczuk, J. O.; Atanasov, A. G. (2018). "Ethnopharmacological Approaches for Dementia Therapy and Significance of Natural Products and Herbal Drugs". Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 10: 3. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2018.00003. PMC 5816049. PMID 29483867.

- Laws KR, Sweetnam H, Kondel TK (November 2012). "Is Ginkgo biloba a cognitive enhancer in healthy individuals? A meta-analysis". Hum Psychopharmacol (Meta-analysis). 27 (6): 527–533. doi:10.1002/hup.2259. PMID 23001963.

- "Ginkgo". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, US National Institutes of Health. 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- Birks, J; Grimley Evans, J (21 January 2009). "Ginkgo biloba for cognitive impairment and dementia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Systematic review) (1): CD003120. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003120.pub3. PMID 19160216.

- Cooper, C; Li, R; Lyketsos, C; Livingston, G (September 2013). "Treatment for mild cognitive impairment: systematic review". British Journal of Psychiatry (Systematic review). 203 (3): 255–264. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.113.127811. PMC 3943830. PMID 24085737.

- Xiong XJ, Liu W, Yang XC, et al. (September 2014). "Ginkgo biloba extract for essential hypertension: A systemic review". Phytomedicine (Systematic review). 21 (10): 1131–1136. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2014.04.024. PMID 24877716.

- Clement, YN; Onakpoya, I; Hung, SK; Ernst, E (March 2011). "Effects of herbal and dietary supplements on cognition in menopause: a systematic review". Maturitas (Systematic review). 68 (3): 256–263. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.12.005. PMID 21237589.

- Hilton, MP; Zimmermann, EF; Hunt, WT (28 March 2013). "Ginkgo biloba for tinnitus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Systematic review). 3 (3): CD003852. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003852.pub3. PMID 23543524.

- Zeng X, Liu M, Yang Y, Li Y, Asplund K (2005). "Ginkgo biloba for acute ischaemic stroke". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Systematic review) (4): CD003691. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003691.pub2. PMID 16235335.

- Nicolaï SP, Kruidenier LM, Bendermacher BL, et al. (2013). "Ginkgo biloba for intermittent claudication". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Systematic review). 6 (6): CD006888. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006888.pub3. PMID 23744597.

- Evans, JR (31 January 2013). "Ginkgo biloba extract for age-related macular degeneration" (PDF). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Systematic review). 1 (1): CD001775. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001775.pub2. PMID 23440785.

- Gertsch JH, Basnyat B, Johnson EW, Onopa J, Holck PS (3 April 2004). "Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled comparison of ginkgo biloba and acetazolamide for prevention of acute mountain sickness among Himalayan trekkers: The prevention of high altitude illness trial (PHAIT)". BMJ. 328 (7443): 797. doi:10.1136/bmj.38043.501690.7C. PMC 383373. PMID 15070635.

- Seupaul, RA; Welch, JL; Malka, ST; Emmett, TW (April 2012). "Pharmacologic prophylaxis for acute mountain sickness: A systematic shortcut review". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 59 (4): 307–317.e1. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.10.015. PMID 22153998.

- Jiang X, Williams KM, Liauw WS, Ammit AJ, Roufogalis BD, Duke CC, Day RO, McLachlan AJ (April 2005). "Effect of ginkgo and ginger on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of warfarin in healthy subjects". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 59 (4): 425–432. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02322.x. PMC 1884814. PMID 15801937.

- "MedlinePlus Herbs and Supplements: Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba L.)". National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

- "Ginkgo biloba". University of Maryland Medical Center. Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

- "Ginkgo Uses, Benefits & Dosage – Drugs.com Herbal Database".

- Dugoua, J. J.; Mills, E.; Perri, D.; Koren, G. (2006). "Safety and efficacy of ginkgo (ginkgo biloba) during pregnancy and lactation". Can J Clin Pharmacol. 13 (3): e277–e284. PMID 17085776. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- Xian-guo; et al. (2000). "High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Electrospray Ionization-Mass Spectrometry Study of Ginkgolic Acid in the Leaves and Fruits of the Ginkgo Tree (Ginkgo biloba)". Journal of Chromatographic Science. 38 (4): 169–173. doi:10.1093/chromsci/38.4.169. PMID 10766484.

- Tanaka, A; Arai, Y; Kim, SN; Ham, J; Usuki, T (2011). "Synthesis and biological evaluation of bilobol and adipostatin A". Journal of Asian Natural Products Research. 13 (4): 290–296. doi:10.1080/10286020.2011.554828. PMID 21462031.

- Kobayashi, Daisuke (2019). "Food poisoning by Ginkgo seeds through vitamin B6 depletion (article in Japanese)". Yakugaku Zasshi. 139 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1248/yakushi.18-00136. ISSN 0031-6903. PMID 30606915.

- Wada, Keiji; Ishigaki, Seikou; Ueda, Kaori; Sakata, Masakatsu; Haga, Masanobu (1985). "An antivitamin B6, 4'-methoxypyridoxine, from the seed of Ginkgo biloba L.". Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 33 (8): 3555–3557. doi:10.1248/cpb.33.3555. ISSN 0009-2363. PMID 4085085.

- Ogren, Thomas Leo (2000). Allergy-Free Gardening. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-58008-166-5.

- "RHS Plantfinder - Ginkgo biloba 'Troll'". Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- "AGM Plants - Ornamental" (PDF). Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 43. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- Gilman, Edward F.; Dennis G. Watson (1993). "Ginkgo biloba 'Autumn Gold'" (PDF). US Forest Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- Boland, Timothy; Laura E. Coit; Marty Hair (2002). Michigan Gardener's Guide. Cool Springs Press. ISBN 978-1-930604-20-9.

- "Examples of Plants with Insect and Disease Tolerance". SULIS - Sustainable Urban Landscape Information Series. University of Minnesota. Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- "The official logo of Osaka University". Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- "A-bombed Ginkgo trees in Hiroshima, Japan". The Ginkgo Pages.

- "10-The Great Ginkgo大銀杏". Tsurugaoka Hachimangu. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- Huxley, Anthony (9 August 1987). "He Gave Us the Gingko". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Ginkgo biloba |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ginkgo biloba. |

.jpg)