Fetal warfarin syndrome

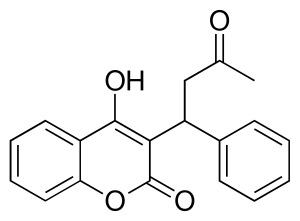

Fetal warfarin syndrome is a disorder of the embryo which occurs in a child whose mother took the medication warfarin (brand name: Coumadin) during pregnancy. Resulting abnormalities include low birth weight, slower growth, mental retardation, deafness, small head size, and malformed bones, cartilage, and joints.[1]

| Fetal warfarin syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Warfarin | |

| Specialty | Teratology |

| Usual onset | Embryo |

| Causes | Maternal warfarin administration |

| Diagnostic method | Observation of key symptoms |

| Prevention | Avoid administration of warfarin during pregnancy |

| Treatment | Administer Vitamin K and plasma with clotting factors. Surgical correction |

Warfarin is an oral anticoagulant drug (blood thinner) used to reduce blood clots, deep vein thrombosis, and embolism in people with prosthetic heart valves, atrial fibrillation, or those who have suffered ischemic stroke.[2] Warfarin blocks the action of vitamin K, causing an inhibition of blood clotting factors and the pro-bone-building hormone osteocalcin.

Warfarin is a teratogen which can cross from the mother to the developing fetus. The inhibition of clotting factors can lead to internal bleeding of the fetus while the inhibition of osteocalcin causes lower bone growth. As well as birth defects, warfarin can induce spontaneous abortion or stillbirth.[3] Because of this, warfarin is contraindicated during pregnancy.

Signs and symptoms

The key symptoms, visible at birth, vary between individuals exposed to warfarin in utero. The severity and occurrence of symptoms is dose dependent with higher doses (>5 mg warfarin daily) more likely to cause immediately noticeable defects.[4]

The period of pregnancy in which warfarin is administered can affect the category of defects which develop. Warfarin taken in the first trimester of pregnancy is more likely to result in physical abnormalities while warfarin taken in the second and third trimester more commonly causes abnormalities of the central nervous system. The more extreme symptoms such as severe mental retardation, blindness and deafness occur more often when warfarin is used throughout all three trimesters.[3]

Growth

Babies born with fetal warfarin syndrome may have a below-average birth weight and do continue to grow at a reduced rate.[5]

Facial features

Children with fetal warfarin syndrome show many otolaryngological abnormalities consistent with abnormal bone and cartilage growth. Children may present with hypoplasia of the nasal ridge and a deep groove at the midline of the nose,[3] thinned or absent nasal septum,[6] choanal atresia; a narrowing the airway at the posterior nasal cavity, cleft lip and laryngomalacia;[3] large soft protrusions into the larynx. These facial defects and narrowing of the airways often lead to respiratory distress, noisy breathing and later; speech defects. Narrow airways often widen with age and allow for easier breathing.[3] Dental problems are also seen with abnormally large dental buds and late eruption of deciduous teeth.[6]

Development of the eyes is also affected by warfarin. Microphthalmia; abnormally small eyes, telecanthus; abnormally far apart eyes and strabismus; misaligned or crossed eyes are common signs of fetal warfarin syndrome.[6] The appearance of an ectopic lacrimal duct, where the tear duct protrudes laterally onto the eye has also been noted.[6]

Bodily features

Whole body skeletal abnormalities are common in fetal warfarin syndrome. A generalized reduction in bone size causes rhizomelia; disproportionally short limbs, brachydactyly; short fingers and toes,[3] a shorter neck,[6] short trunk, scoliosis; abnormal curvature of the spine and stippled epiphyses; malformation of joints. Abnormalities of the chest: either pectus carinatum;[3] a protruding sternum, or pectus excavatum;[6] a sunken sternum form an immediately recognizable sign of fetal warfarin syndrome.

Congenital heart defects such as a thinned atrial septum, coarctation of the aorta, patent ductus arteriosus; a connection between the pulmonary artery and aorta occur in 8% of fetal warfarin syndrome patients. Situs inversus totalis, the complete left-right mirroring of thoracic organs, has also been observed

CNS

Defects of the central nervous system can lead to profound mental challenges. Fetal warfarin syndrome can lead to microcephaly; an abnormally small head, hydrocephaly; increased ventricle size and CSF volume, and agenesis of the corpus callosum. These defects contribute to the appearance of significant mental retardation in 31% of fetal warfarin syndrome cases.[3] Hypotonia, whole body muscle relaxation, can appear in newborns with severe nervous deficits. Atrophy of the optic nerve can also cause blindness in fetal warfarin syndrome.[7]

Physiological

Inhibition of coagulation and resultant internal bleeding can cause too few red blood cells to be present in the bloodstream and low blood pressure in newborns with fetal warfarin syndrome.[5] Low hemoglobin levels can lead to partial oxygen starvation, a high level of lactic acid in the bloodstream, and acidosis. Prolonged oozing of fluid from the stump of the cut umbilical cord is common.

Cause

Fetal warfarin syndrome appears in greater than 6% of children whose mothers took warfarin during pregnancy.[3] Warfarin has a low molecular weight so can pass from the maternal to fetal bloodstream through the tight filter-like junctions of the placental barrier.

As the teratogenic effects of warfarin are well known, the medication is rarely prescribed to pregnant women. However, for some patients, the risks associated with discontinuing warfarin use may outweigh the risk of embryopathy. Patients with prosthetic heart valves carry a particularly high risk of thrombus formation due to the inorganic surface and turbulent blood flow generated by a mechanical prosthesis. The risk of blood clotting is further increased by generalized hypercoagulability as concentrations of clotting factors rise during pregnancy.[8] This increased chance of blood clots leads to an increased risk of potentially fatal pulmonary or systemic emboli cutting of blood flow and oxygen to critical organs. Thus, some patients may continue taking warfarin throughout the pregnancy despite the risks to the developing child.

Mechanism

Warfarin’s ability to cause fetal warfarin syndrome in utero stems from its ability to limit vitamin K activation.[3] Warfarin binds to and blocks the enzyme Vitamin K epoxide reductase which is usually responsible for activating vitamin K during vitamin K recycling. Vitamin K, once activated, is able to add a carboxylic acid group to glutamate residues of certain proteins which assists in correct protein folding.[9] Without active vitamin K, a fetus exposed to warfarin is unable to produce large quantities of clotting and bone growth factors.

Without vitamin K, clotting factors II, VII, IX and X are unable to be produced. Without these vital parts of the coagulation cascade a durable fibrin plug cannot form to block fluid escaping from damaged or permeable vasculature.[2] Anemia is common in fetuses exposed to warfarin as blood constantly seeps into the interstitial fluid or amniotic cavity.[5] High doses of warfarin and heavy bleeding lead to abortion and stillbirth.

Osteocalcin is another protein dependent on vitamin K for correct folding and function. Osteocalcin is normally secreted by osteoblast cells and plays a role in aiding correct bone mineralization and bone maturation.[10] In the presence of warfarin and subsequent absence of vitamin K and active osteocalcin, bone mineralization and growth are stunted.

Prevention

Fetal warfarin syndrome is prevented by withholding prescription to pregnant women or those trying to conceive. As warfarin can remain in the mother’s body for up to five days,[11] warfarin should not be administered in the days leading up to conception. Doctors must take care to ensure women of reproductive age are aware of the risks to the baby should they get pregnant, before prescribing warfarin.

For some women, such as those with prosthetic heart valves, anticoagulation medication cannot be suspended during pregnancy as the risk of thrombus and emboli is too high. In such cases an alternate anticoagulant, which cannot pass through the placental barrier to the fetus, is proscribed in place of warfarin. Heparin is one such anticoagulant medication, although its efficacy in patients with prosthetic heart valves is not well established.[12] New anticoagulant medications, which are efficacious and non-teratogenic such as ximelagatran continue to be developed.[3]

Management

Medication

As well as the routine dose of vitamin K given to newborns after birth, babies born with fetal warfarin syndrome are given additional doses intramuscularly to overcome any remaining warfarin in the circulation and prevent further bleeding. Fresh frozen plasma is also administered to raise concentrations of active blood clotting factors. If the child is anemic from extensive bleeding in-utero, red blood cell concentrate is given to restore oxygen carrying capacity.[5]

Surgical correction

Surgical interventions can be given to improve functionality and correct cosmetic abnormalities. Osteotomy (bone cutting) and zetaplasty surgeries are used to cut away abnormal tissue growths at the piriform aperture around and pharynx to reduce airway obstruction.[6] Rhinoplasty surgery is used to restore normal appearance and function of the nose.[6] Heart surgery may also be required to close a patent ductus arteriosus.

References

- Yurdakök, M. 2012, "Fetal and neonatal effects of anticoagulants used in pregnancy: a review", The Turkish journal of pediatrics, vol. 54, no. 3, pp. 207.

- Reid, A., Forrester, C. & Shwe, K. 2009, "Warfarin", Student BMJ, vol. 17.

- Hou, J. 2004, "Fetal warfarin syndrome", Chang Gung medical journal, vol. 27, no. 9, pp. 691.

- Vitale, N., De Feo, M., De Santo, L.S., Pollice, A., Tedesco, N. & Cotrufo, M. 1999, "Dose-dependent fetal complications of warfarin in pregnant women with mechanical heart valves", Journal of the American College of Cardiology, vol. 33, no. 6, pp. 1637-1641.

- Starling, L.D., Sinha, A., Boyd, D. & Furck, A. 2012, "Fetal warfarin syndrome", BMJ case reports, vol. 2012, no. 1, pp. 1-4

- Silveira, D.B., da Rosa, E.B., de Mattos, V.F., Goetze, T.B., Sleifer, P., Santa Maria, F.D., Rosa, R.C.M., Rosa, R.F.M. & Zen, P.R.G. 2015, "Importance of a multidisciplinary approach and monitoring in fetal warfarin syndrome", American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, vol. 167, no. 6, pp. 1294-1299.

- Raghav, S. & Reutens, D. 2006;2007;, "Neurological sequelae of intrauterine warfarin exposure", Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 99-103.

- Maiello, M., Torella, M., Caserta, L., Caserta, R., Sessa, M., Tagliaferri, A., Bernacchi, M., Napolitano, M., Nappo, C., De Lucia, D. & Panariello, S. 2006, "Hypercoagulability during pregnancy: evidences for a thrombophilic state", Minerva ginecologica, vol. 58, no. 5, pp. 417.

- Danziger, J. 2008, "Vitamin K-dependent Proteins, Warfarin, and Vascular Calcification", Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 1504-1510.

- Yamauchi, M., Yamaguchi, T., Nawata, K., Takaoka, S. & Sugimoto, T. 2010, "Relationships between undercarboxylated osteocalcin and vitamin K intakes, bone turnover, and bone mineral density in healthy women", Clinical Nutrition, vol. 29, no. 6, pp. 761-765.

- Walfisch, A. & Koren, G. 2010, "The "Warfarin Window" in Pregnancy: The Importance of Half-life", Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology Canada, vol. 32, no. 10, pp. 988.

- Loftus, C. (1996). Neurosurgical aspects of pregnancy. Park Ridge, Ill.: American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

External links

| Classification |

|---|