Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex

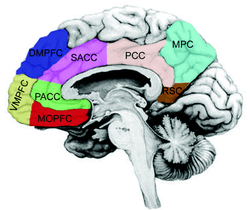

The dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC[1][2] or DMPFC[3][4]) is a section of the prefrontal cortex in some species' brain anatomy. It includes portions of Brodmann areas BA8, BA9, BA10, BA24 and BA32,[5] although some authors identify it specifically with BA8 and BA9[3][6] Some notable sub-components include the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (BA24 and BA32),[1][5] the prelimbic cortex,[1][5] and the infralimbic cortex.[2]

| Dorsomedial Prefrontal Cortex | |

|---|---|

The location of the Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex is marked as "DMPFC" | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Prefrontal Cortex |

| Parts | Anterior cingulate cortex, Prelimbic cortex |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

Functions

Evidence shows that the dmPFC plays several roles in humans. The dmPFC is identified to play roles in processing a sense of self, integrating social impressions, theory of mind, morality judgments, empathy, decision making, altruism, fear and anxiety information processing, and top-down motor cortex inhibition (Gusnard, Akbudak, Shulman, & Raichle2001; Ferrari et al., 2016; Narayanan & Laubach, 2006; Waytz, Zaki, & Mitchell 2012; Mitchell, Banaji, & Macrae, 2005 in Ferrari et al., 2016). The dmPFC also modulates or regulates emotional responses and heart rate in situations of fear or stress and plays a role in long-term memory (Corsi & Christen, 2012; Decety & Batson, 2007). Some argue that the dmPFC is made up of several smaller subregions that are more task-specific (Eickhoff, Laird, Fox, Bzdok, & Hensel, 2016). The dmPFC is attributed with many roles in the brain. Despite this, there is no definitive understanding of the exact role dmPFC plays, and the underlying mechanisms giving rise to its function(s) in the brain remain to be seen.

Identity

The dmPFC is thought to be one component of how people formulate an identity, or a sense of self (Gusnard et al., 2001; Meares, 2012). When actors were tasked with performing a character, fMRI scans showed relative suppression of the dmPFC compared to baseline tasks (Brown, Cockett, & Yuan, 2019). This same deactivation was not seen in the other tasks performed by the actors. The authors theorize that this may be due to the actors actively suppressing their own sense of self in order to portray another character. Similarly, the dmPFC has been shown to be inactive in individuals with psychological disassociation (Meares, 2012).

Social Judgments and Theory of Mind

Mitchell et al. (2005, in Ferrari et al., 2016) indicated that the dmPFC plays a role in creating social impressions. One study showed that by using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to the dmPFC during a social judgment task directly disrupts a person’s ability to form social judgments (Ferrari et al., 2016). Additionally, the dmPFC is active when people are trying to understand the perspectives, beliefs, and thoughts of others; this is known as Theory of Mind (Isoda & Noritake, 2013). The dmPFC has also been shown to play a role in altruism. The amount that a person’s dmPFC was active during a socially-based task predicted how much money that person would later donate to others (Waytz, Zaki, & Mitchell, 2012). Furthermore, the dmPFC has been shown to be play a role in morality decisions (Bzdok et al., 2012).

Emotion

The dmPFC has been shown to be involved in voluntary and involuntary emotional regulation (Ford & Kensinger, 2019; Phillips, Ladouceur, & Drevets, 2008). When recalling negative memories, older adults show activation in the dmPFC. This is believed to act as mechanism that reduces the overall experienced negativity of the event (Ford & Kensinger, 2019). The dmPFC is thought to be impaired in individuals diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder resulting in disrupted emotional regulation (Phillips et al., 2008).

Decision Making

In addition to social judgments, the dmPFC shows increased activation during complex decision making tasks. (Venkatraman, Rosati, Taren, & Huettel, 2009). Other studies have shown increased activation in the dmPFC when a person must decide between two equally-likely outcomes, as well as when a decision is counter to their behavioral tendencies (Pochon et al., 2008 and Paulus et al., 2002 in Venkatraman et al., 2009)

Other species

The DMPFC can also be identified in monkeys.[7] The prelimbic system in mice is believed to be functionally analogous to the dmPFC's emotional regulation function in humans.[8]

Animal Models

In rats, the dmPFC has been shown to exert top-down control over the motor regions, although the exact mechanisms of how this is accomplished remain unknown (Narayanan & Laubach, 2006). Researchers have shown in mice that the dmPFC 5-HT6 receptors play a role in regulating anxiety-like behaviors (Geng et al., 2018). Another study looked at how dopamine receptors in the dmPFC play a role in regulating fear in rats (Stubbendorff, Hale, Cassaday, Bast, & Stevenson, 2019)

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prefrontal cortex. |

- Self-model theory of subjectivity

References

- Corsi, P.S.; Christen, Y. (2012). Epigenetics, Brain and Behavior. Research and Perspectives in Neurosciences. Springer. p. 88. ISBN 978-3-642-27912-6. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- Gamond, L.; Cattaneo, Z. (2016). The Dorsomedial Prefrontal Cortex Plays a Causal Role in Mediating In-group Advantage in Emotion Recognition: A TMS Study. Elsevier.

- Lieberman, M.D. (2013). Social: Why Our Brains are Wired to Connect. OUP Oxford. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-19-964504-6.

- Leary, M.R.; Tangney, J.P. (2012). Handbook of Self and Identity. Guilford Publications. p. 640. ISBN 978-1-4625-0305-6. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Dougherty, D.D.; Rauch, S.L. (2008). Psychiatric Neuroimaging Research: Contemporary Strategies. American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-58562-790-5.

- Brookhart, J.M.; Mountcastle, V.B.; Brooks, V.B.; Geiger, S.R. (1981). Handbook of physiology: a critical, comprehensive presentation of physiological knowledge and concepts. Handbook of Physiology: A Critical, Comprehensive Presentation of Physiological Knowledge and Concepts. American Physiological Society. ISBN 978-0-683-01105-0.

- Acton, Q.A. (2013). Advances in Basal Ganglia Research and Application. Atlanta, GA: ScholarlyEditions. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-4816-6955-9. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

Brown, S., Cockett, P., & Yuan, Y. (2019). The neuroscience of Romeo and Juliet: An fMRI study of acting. Royal Society Open Science, 6(3). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.181908

Bzdok, D., Schilbach, L., Vogeley, K., Schneider, K., Laird, A. R., Langner, R., & Eickhoff, S. B. (2012). Parsing the neural correlates of moral cognition: ALE meta-analysis on morality, theory of mind, and empathy. Brain Structure and Function, 217(4), 783–796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-012-0380-y

Corsi, P.S.; Christen, Y. (2012). Epigenetics, Brain and Behavior. Research and Perspectives in Neurosciences. Springer. p. 88. ISBN 978-3-642-27912-6. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

Decety, J.; Batson, C.D. (2007). Interpersonal Sensitivity - Entering Others' Worlds. Social neuroscience. Psychology Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-84169-838-0.

Eickhoff, S. B., Laird, A. R., Fox, P. T., Bzdok, D., & Hensel, L. (2016). Functional Segregation of the Human Dorsomedial Prefrontal Cortex. Cerebral Cortex, 26(1), 304–321. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhu250

Ferrari, C., Lega, C., Vernice, M., Tamietto, M., Mende-Siedlecki, P., Vecchi, T., … Cattaneo, Z. (2016). The Dorsomedial Prefrontal Cortex Plays a Causal Role in Integrating Social Impressions from Faces and Verbal Descriptions. Cerebral Cortex, 26(1), 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhu186

Ford, J. H., & Kensinger, E. A. (2019). Older adults recruit dorsomedial prefrontal cortex to decrease negativity during retrieval of emotionally complex real-world events. Neuropsychologia, 135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2019.107239

Geng, F., Tian, J., Wu, J. L., Luo, Y., Zou, W. J., Peng, C., & Lu, G. F. (2018). Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex 5-HT6 receptors regulate anxiety-like behavior. Cognitive, Affective and Behavioral Neuroscience, 18(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-017-0552-6

Gusnard, D. A., Akbudak, E., Shulman, G. L., & Raichle, M. E. (2001). Medial prefrontal cortex and self-referential mental activity: relation to a default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(7), 4259-4264.

Isoda, M., & Noritake, A. (2013). What makes the dorsomedial frontal cortex active during reading the mental states of others? Frontiers in Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2013.00232

Meares, R. (2012). A dissociation model of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: W.W. Norton. p. 109. ISBN 9780393705850. Narayanan, N. S., & Laubach, M. (2006). Top-Down Control of Motor Cortex Ensembles by Dorsomedial Prefrontal Cortex. Neuron, 52(5), 921–931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.021

Phillips, M. L., Ladouceur, C. D., & Drevets, W. C. (2008). A neural model of voluntary and automatic emotion regulation: Implications for understanding the pathophysiology and neurodevelopment of bipolar disorder. Molecular Psychiatry, Vol. 13, pp. 833–857. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2008.65

Stubbendorff, C., Hale, E., Cassaday, H. J., Bast, T., & Stevenson, C. W. (2019). Dopamine D1-like receptors in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex regulate contextual fear conditioning. Psychopharmacology, 236(6), 1771–1782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-018-5162-7

Venkatraman, V., Rosati, A. G., Taren, A. A., & Huettel, S. A. (2009). Resolving response, decision, and strategic control: Evidence for a functional topography in dorsomedial prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 29(42), 13158–13164. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2708-09.2009

Waytz, A., Zaki, J., & Mitchell, J. P. (2012). Response of dorsomedial prefrontal cortex predicts altruistic behavior. Journal of Neuroscience, 32(22), 7646–7650. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6193-11.2012