Excavata

Excavata is a major supergroup of unicellular organisms belonging to the domain Eukaryota.[1][2][3] It was first suggested by Simpson and Patterson in 1999[4][5] and introduced by Thomas Cavalier-Smith in 2002 as a new phylogenetic category, it contains a variety of free-living and symbiotic forms, and also includes some important parasites of humans, including Giardia and Trichomonas.[6] Excavates were formerly considered to be included in the now obsolete Protista kingdom.[7] They are classified based on their flagellar structures,[5] and they are considered to be the most basal Flagellate lineage.[8] Except for Euglenozoa, they are all non-photosynthetic.

| Excavata Temporal range: Neoproterozoic–present Had'n

Archean

Proterozoic

Pha.

| |

|---|---|

| |

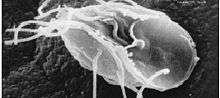

| Giardia lamblia, a parasitic diplomonad | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| (unranked): | Excavata (Cavalier-Smith), 2002 |

| Phyla | |

| |

Characteristics

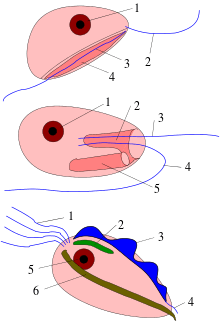

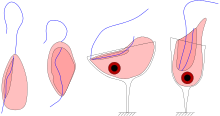

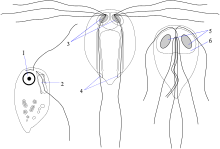

Most excavates are unicellular, heterotrophic flagellates. Only the Euglenozoa are photosynthetic. In some (particularly anaerobic intestinal parasites), the mitochondria have been greatly reduced.[6] They often lack "classical" mitochondria—these organisms are often referred to as "amitochondriate", although most retain a mitochondrial organelle in greatly modified form (e.g. a hydrogenosome or mitosome). Among those with mitochondria, the mitochondrial cristae may be tubular, discoidal, or in some cases, laminar. Most excavates have two, four, or more flagella[5] and many have a conspicuous ventral feeding groove with a characteristic ultrastructure, supported by microtubules (with the term "excavate" deriving from the organisms showing clear evidence of this "excavated" feeding groove).[4][7] However, various groups that lack these traits may be considered excavates based on genetic evidence (primarily phylogenetic trees of molecular sequences).[7]

The Acrasidae slime molds are the only excavates to exhibit limited multicellularity. Like other cellular slime molds, they live most of their life as single cells, but will sometimes assemble into larger clusters.

Classification

Excavates are classified into six major subdivisions at the phylum/class level. These are shown in the table below. An additional organism, Malawimonas, may also be included amongst excavates, though phylogenetic evidence is equivocal.

| Kingdom/Superphylum | Phylum/Class | Representative genera (examples) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discoba or JEH or Eozoa | Tsukubea | T. globosa | |

| Euglenozoa | Euglena, Trypanosoma | Many important parasites, one large group with plastids (chloroplasts) | |

| Heterolobosea (Percolozoa) | Naegleria, Acrasis | Most alternate between flagellate and amoeboid forms | |

| Jakobea | Jakoba, Reclinomonas | Free-living, sometimes loricate flagellates, with very gene-rich mitochondrial genomes | |

| Metamonada or POD | Preaxostyla | Oxymonads, Trimastix | Amitochondriate flagellates, either free-living (Trimastix, Paratrimastix) or living in the hindguts of insects |

| Fornicata | Giardia, Carpediemonas | Amitochondriate, mostly symbiotes and parasites of animals. | |

| Parabasalia | Trichomonas | Amitochondriate flagellates, generally intestinal commensals of insects. Some human pathogens. | |

| Neolouka | Malawimonas | ||

| Ancyromonadida |

Discoba or JEH clade

Euglenozoa and Heterolobosea (Percolozoa) or Eozoa (Cavalier-Smith) appear to be particularly close relatives, and are united by the presence of discoid cristae within the mitochondria (Superphylum Discicristata). More recently a close relationship has been shown between Discicristata and Jakobida,[9] the latter having tubular cristae like most other protists, and hence were united under the taxon name Discoba, which was proposed for this apparently monophyletic group.[2]

Metamonads

Metamonads are unusual in having lost classical mitochondria—instead they have hydrogenosomes, mitosomes or uncharacterised organelles. The oxymonad Monocercomonoides is reported to have completely lost homologous organelles.

Monophyly

Excavate relationships are still uncertain; it is possible that they are not a monophyletic group. The monophyly of the excavates is far from clear, although there seem to be several clades within the excavates that are monophyletic.[10]

Certain excavates are often considered among the most primitive eukaryotes, based partly on their placement in many evolutionary trees. This could encourage proposals that excavates are a paraphyletic grade that includes the ancestors of other living eukaryotes. However, the placement of certain excavates as 'early branches' may be an analysis artifact caused by long branch attraction, as has been seen with some other groups, for example, microsporidia.

Malawimonas and Ancyromonads

In addition to the groups mentioned in the table above, the genus Malawimonas and the Ancyromonads are generally considered to be members of Excavata owing to their typical excavate morphology, and phylogenetic affinity to excavate groups in some molecular phylogenies. However, their position among excavates remains elusive.[3]

Cladogram

Here is a proposed cladogram for the positioning of the Excavata, with the Eukaryote root in the excavates, mainly following Cavalier-Smith.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19]

| Eukaryota |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In this view, excavata is highly paraphyletic, and is proposed to be abandoned.[20] In alternative view, the Discoba are sister to the rest of the Diphoda.[12][21]

| Eukaryota |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

Euglena (Euglenozoa: Euglenoida)

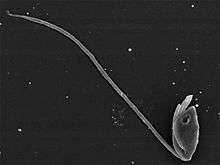

Euglena (Euglenozoa: Euglenoida) Trypanosoma brucei (Euglenozoa: Kinetoplastida)

Trypanosoma brucei (Euglenozoa: Kinetoplastida).jpg) Bodo sp. (Euglenozoa: Kinetoplastida)

Bodo sp. (Euglenozoa: Kinetoplastida) Percolomonas sp. (Percolozoa)

Percolomonas sp. (Percolozoa) Stephanopogon sp. (Percolozoa)

Stephanopogon sp. (Percolozoa).png)

Acrasis rosea (Percolozoa: Heterolobosea)

Acrasis rosea (Percolozoa: Heterolobosea) Jakobids (Jakobida)

Jakobids (Jakobida)

Giardia sp. (Metamonada: Fornicata: Diplomonadida)

Giardia sp. (Metamonada: Fornicata: Diplomonadida)

References

- Hampl, V.; Hug, L.; Leigh, J. W.; Dacks, J. B.; Lang, B. F.; Simpson, A. G. B.; Roger, A. J. (2009). "Phylogenomic analyses support the monophyly of Excavata and resolve relationships among eukaryotic "supergroups"". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (10): 3859–3864. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.3859H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0807880106. PMC 2656170. PMID 19237557.

- Hampl V, Hug L, Leigh JW, et al. (2009). "Phylogenomic analyses support the monophyly of Excavata and resolve relationships among eukaryotic "supergroups"". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (10): 3859–64. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.3859H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0807880106. PMC 2656170. PMID 19237557.

- Simpson, Ag; Inagaki, Y; Roger, Aj (2006). "Comprehensive multigene phylogenies of excavate protists reveal the evolutionary positions of "primitive" eukaryotes". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (3): 615–25. doi:10.1093/molbev/msj068. PMID 16308337.

- Simpson, Alastair G.B.; Patterson, David J. (Dec 1999). "The ultrastructure of Carpediemonas membranifera (Eukaryota) with reference to the 'excavate hypothesis'". European Journal of Protistology. 35 (4): 353–370. doi:10.1016/S0932-4739(99)80044-3.

- Simpson, Alastair G.B. (2003-11-01). "Cytoskeletal organization, phylogenetic affinities and systematics in the contentious taxon Excavata (Eukaryota)". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 53 (6): 1759–1777. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02578-0. ISSN 1466-5026. PMID 14657103.

- Dawkins, Richard; Wong, Yan (2016). The Ancestor's Tale. ISBN 978-0544859937.

- Cavalier-Smith, T (2002). "The phagotrophic origin of eukaryotes and phylogenetic classification of Protozoa". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 52 (2): 297–354. doi:10.1099/00207713-52-2-297. PMID 11931142.

- Dawson, Scott C; Paredez, Alexander R (2013). "Alternative cytoskeletal landscapes: cytoskeletal novelty and evolution in basal excavate protists". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 25 (1): 134–141. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2012.11.005. PMC 4927265. PMID 23312067.

- Naiara Rodríguez-Ezpeleta; Henner Brinkmann; Gertraud Burger; Andrew J. Roger; Michael W. Gray; Hervé Philippe & B. Franz Lang (2007). "Toward Resolving the Eukaryotic Tree: The Phylogenetic Positions of Jakobids and Cercozoans". Curr. Biol. 17 (16): 1420–1425. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.036. PMID 17689961.

- Laura Wegener Parfrey; Erika Barbero; Elyse Lasser; Micah Dunthorn; Debashish Bhattacharya; David J Patterson; Laura A Katz (2006). "Evaluating Support for the Current Classification of Eukaryotic Diversity". PLoS Genet. 2 (12): e220. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020220. PMC 1713255. PMID 17194223.

- Cavalier-Smith, Thomas; Chao, Ema E.; Lewis, Rhodri (2016-06-01). "187-gene phylogeny of protozoan phylum Amoebozoa reveals a new class (Cutosea) of deep-branching, ultrastructurally unique, enveloped marine Lobosa and clarifies amoeba evolution". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 99: 275–296. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2016.03.023. PMID 27001604.

- Derelle, Romain; Torruella, Guifré; Klimeš, Vladimír; Brinkmann, Henner; Kim, Eunsoo; Vlček, Čestmír; Lang, B. Franz; Eliáš, Marek (2015-02-17). "Bacterial proteins pinpoint a single eukaryotic root". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (7): E693–E699. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112E.693D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1420657112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4343179. PMID 25646484.

- Cavalier-Smith, T.; Chao, E. E.; Snell, E. A.; Berney, C.; Fiore-Donno, A. M.; Lewis, R. (2014). "Multigene eukaryote phylogeny reveals the likely protozoan ancestors of opisthokonts (animals, fungi, choanozoans) and Amoebozoa". Molecular Phylogenetics & Evolution. 81: 71–85. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.08.012. PMID 25152275.

- Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (2010-06-23). "Kingdoms Protozoa and Chromista and the eozoan root of the eukaryotic tree". Biology Letters. 6 (3): 342–345. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0948. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 2880060. PMID 20031978.

- He, Ding; Fiz-Palacios, Omar; Fu, Cheng-Jie; Fehling, Johanna; Tsai, Chun-Chieh; Baldauf, Sandra L. (2014). "An Alternative Root for the Eukaryote Tree of Life". Current Biology. 24 (4): 465–470. Bibcode:1996CBio....6.1213A. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.036. PMID 24508168.

- Cavelier Smith (2013). "Early evolution of eukaryote feeding modes, cell structural diversity, and classification of the protozoan phyla Loukozoa, Sulcozoa, and Choanozoa". European Journal of Protistology. 49 (2): 115–178. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2012.06.001. PMID 23085100.

- Hug, Laura A.; Baker, Brett J.; Anantharaman, Karthik; Brown, Christopher T.; Probst, Alexander J.; Castelle, Cindy J.; Butterfield, Cristina N.; Hernsdorf, Alex W.; Amano, Yuki (2016-04-11). "A new view of the tree of life". Nature Microbiology. 1 (5): 16048. doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.48. ISSN 2058-5276. PMID 27572647.

- Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (2017-09-05). "Kingdom Chromista and its eight phyla: a new synthesis emphasising periplastid protein targeting, cytoskeletal and periplastid evolution, and ancient divergences". Protoplasma. 255 (1): 297–357. doi:10.1007/s00709-017-1147-3. ISSN 0033-183X. PMC 5756292. PMID 28875267.

- Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (2017). "Euglenoid pellicle morphogenesis and evolution in light of comparative ultrastructure and trypanosomatid biology: semi-conservative microtubule/strip duplication, strip shaping and transformation". European Journal of Protistology. 61 (Pt A): 137–179. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2017.09.002. PMID 29073503.

- Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (2016-10-01). "Higher classification and phylogeny of Euglenozoa". European Journal of Protistology. 56: 250–276. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2016.09.003. PMID 27889663.

- Yabuki, Akinori; Kamikawa, Ryoma; Ishikawa, Sohta A.; Kolisko, Martin; Kim, Eunsoo; Tanabe, Akifumi S.; Kume, Keitaro; Ishida, Ken-ichiro; Inagki, Yuji (2014-04-10). "Palpitomonas bilix represents a basal cryptist lineage: insight into the character evolution in Cryptista". Scientific Reports. 4 (1): 4641. Bibcode:2014NatSR...4E4641Y. doi:10.1038/srep04641. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 3982174. PMID 24717814.

External links

- Open Tree of Life

- Taxonomicon

- Tree of Life Eukaryotes

- Tree of Life: Jakobida

- Tree of Life: Fornicata