Diltiazem

Diltiazem, sold under the trade name Cardizem among others, is a calcium channel blocker used to treat high blood pressure, angina, and certain heart arrhythmias.[1] It may also be used in hyperthyroidism if beta blockers cannot be used.[1] It is taken by mouth or injection into a vein.[1] When given by injections effects typically begin within a few minutes and last a few hours.[1]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /dɪlˈtaɪəzɛm/ |

| Trade names | Cardizem, Dilacorxr, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a684027 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous |

| Drug class | Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blocker |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 40% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 3–4.5 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney Biliary |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.050.707 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C22H26N2O4S |

| Molar mass | 414.519 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include swelling, dizziness, headaches, and low blood pressure.[1] Other severe side effects include an overly slow heart beat, heart failure, liver problems, and allergic reactions.[1] Use is not recommended during pregnancy.[1] It is unclear if use when breastfeeding is safe.[2]

Diltiazem works by relaxing the smooth muscle in the walls of arteries, resulting in them opening and allowing blood to flow more easily.[1] Additionally, it acts on the heart to prolong the period until it can beat again.[3] It does this by blocking the entry of calcium into the cells of the heart and blood vessels.[4] It is a class IV antiarrhythmic.[5]

Diltiazem was approved for medical use in the United States in 1982.[1] It is available as a generic medication.[1] In the United States the wholesale cost per day of the by mouth formulation is less than 0.70 USD as of 2018.[6] In 2016 it was the 63rd most prescribed medication in the United States with more than 12 million prescriptions.[7] An extended release formulation is also available.[1]

Medical uses

Diltiazem is indicated for:

- Stable angina (exercise-induced) – diltiazem increases coronary blood flow and decreases myocardial oxygen consumption, secondary to decreased peripheral resistance, heart rate, and contractility.[8][9]

- Variant angina – it is effective owing to its direct effects on coronary dilation.

- Unstable angina (preinfarction, crescendo) – diltiazem may be particularly effective if the underlying mechanism is vasospasm.

- Myocardial bridge

For supraventricular tachycardias (PSVT), diltiazem appears to be as effective as verapamil in treating re-entrant supraventricular tachycardia.[10]

Atrial fibrillation[11] or atrial flutter is another indication. The initial bolus should be 0.25 mg/kg, intravenous (IV).

Because of its vasodilatory effects, diltiazem is useful for treating hypertension. Calcium channel blockers are well tolerated, and especially effective in treating low-renin hypertension.[12]

Contraindications and precautions

- In congestive heart failure, patients with reduced ventricular function may not be able to counteract the inotropic and chronotropic effects of diltiazem, the result being an even higher compromise of function.

- With SA node or AV conduction disturbances, the use of diltiazem should be avoided in patients with SA or AV nodal abnormalities, because of its negative chronotropic and dromotropic effects.

- Low blood pressure patients, with systolic blood pressures below 90 mm Hg, should not be treated with diltiazem.

- Diltiazem may paradoxically increase ventricular rate in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome because of accessory conduction pathways.

Diltiazem is relatively contraindicated in the presence of sick sinus syndrome, atrioventricular node conduction disturbances, bradycardia, impaired left ventricle function, peripheral artery occlusive disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Side effects

A reflex sympathetic response, caused by the peripheral dilation of vessels and the resulting drop in blood pressure, works to counteract the negative inotropic, chronotropic and dromotropic effects of diltiazem. Undesirable effects include hypotension, bradycardia, dizziness, and flushing.[13]

Diltiazem is one of the most common drugs that cause drug-induced lupus, along with hydralazine, procainamide, isoniazid, minocycline.[14]

Drug interactions

Because of its inhibition of hepatic cytochromes CYP3A4, CYP2C9 and CYP2D6, there are a number of drug interactions.[15] Some of the more important interactions are listed below.

Beta-blockers

Intravenous diltiazem should be used with caution with beta-blockers because, while the combination is most potent at reducing heart rate, there are rare instances of dysrhythmia and AV node block.[16]

Quinidine

Quinidine should not be used concurrently with calcium channel blockers because of reduced clearance of both drugs and potential pharmacodynamic effects at the SA and AV nodes.[17]

Fentanyl

Concurrent use of fentanyl with diltiazem, or any other CYP3A4 inhibitors, as these medications decrease the breakdown of fentanyl and thus increases its effects.[18]

Mechanism

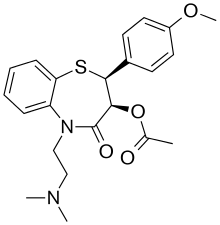

Diltiazem is a potent vasodilator, increasing blood flow and variably decreasing the heart rate via strong depression of A-V node conduction. Its pharmacological activity is somewhat similar to verapamil, another nondihydropyridine (non-DHP) calcium channel blocker.[19] Chemically, it is based upon a 1,4-thiazepine ring, making it a benzothiazepine-type calcium channel blocker.

It is a potent and mild vasodilator of coronary and peripheral vessels, respectively,[20] which reduces peripheral resistance and afterload, though not as potent as the dihydropyridine (DHP) calcium channel blockers. This results in minimal reflexive sympathetic changes.

Diltiazem has negative inotropic, chronotropic, and dromotropic effects. This means diltiazem causes a decrease in heart muscle contractility – how strong the beat is, lowering of heart rate – due to slowing of the sinoatrial node, and a slowing of conduction through the atrioventricular node – increasing the time needed for each beat. Each of these effects results in reduced oxygen consumption by the heart, reducing angina, typically unstable angina, symptoms. These effects also reduce blood pressure by causing less blood to be pumped out.

Research

Diltiazem is prescribed off-label by doctors in the US for prophylaxis of cluster headaches. Some research on diltiazem and other calcium channel antagonists in the treatment and prophylaxis of migraine is ongoing.[8][21][22][23][24][25][26]

Recent research has shown diltiazem may reduce cocaine cravings in drug-addicted rats.[27] This is believed to be due to the effects of calcium blockers on dopaminergic and glutamatergic signaling in the brain.[28] Diltiazem also enhances the analgesic effect of morphine in animal tests, without increasing respiratory depression,[29] and reduces the development of tolerance.[30]

Diltiazem is also being used in the treatment of anal fissures. It can be taken orally or applied topically with increased effectiveness.[31] When applied topically, it is made into a cream form using either vaseline or Phlojel. Phlojel absorbs the diltiazem into the problem area better than the vaseline base. It has good short term success rates.[32][33] Like all nonsurgical treatments of anal fissure, it does not address the long term problem of increased basal anal tone and does not decrease the subsequent recurrence rate that can vary between 40 and 60%.

References

- "Diltiazem Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- "Diltiazem Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapeutics. Cardiotext Publishing. 2011. pp. 251–252. ISBN 9781935395621. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- 2010 Nurse's Drug Handbook. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2010. p. 320. ISBN 9780763779009.

- Milne, G. W. A. (2005). Gardner's Commercially Important Chemicals: Synonyms, Trade Names, and Properties. John Wiley & Sons. p. 223. ISBN 9780471736615. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- "NADAC as of 2018-12-19". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- "The Top 300 of 2019". clincalc.com. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- Grossman E, Messerli FH (2004). "Calcium antagonists". Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 47 (1): 34–57. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2004.04.006. PMID 15517514.

- Claas SA, Glasser SP (May 2005). "Long-acting diltiazem HCl for the chronotherapeutic treatment of hypertension and chronic stable angina pectoris". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 6 (5): 765–76. doi:10.1517/14656566.6.5.765. PMID 15934903.

- Gabrielli A, Gallagher TJ, Caruso LJ, Bennett NT, Layon AJ (October 2001). "Diltiazem to treat sinus tachycardia in critically ill patients: a four-year experience". Critical Care Medicine. 29 (10): 1874–9. doi:10.1097/00003246-200110000-00004. PMID 11588443.

- Wattanasuwan N, Khan IA, Mehta NJ, Arora P, Singh N, Vasavada BC, Sacchi TJ (February 2001). "Acute ventricular rate control in atrial fibrillation: IV combination of diltiazem and digoxin vs. IV diltiazem alone". Chest. 119 (2): 502–6. doi:10.1378/chest.119.2.502. PMID 11171729.

- Basile J (November 2004). "The role of existing and newer calcium channel blockers in the treatment of hypertension". Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 6 (11): 621–29, quiz 630-1. doi:10.1111/j.1524-6175.2004.03683.x. PMID 15538095.

- Ramoska EA, Spiller HA, Winter M, Borys D (February 1993). "A one-year evaluation of calcium channel blocker overdoses: toxicity and treatment". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 22 (2): 196–200. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(05)80202-1. PMID 8427431.

- Solhjoo M, Ho CH, Chauhan E (2019). "article-24529". Drug-Induced Lupus Erythematosus. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 28722919. Retrieved 2019-11-20.

- Ohno Y, Hisaka A, Suzuki H (2007). "General framework for the quantitative prediction of CYP3A4-mediated oral drug interactions based on the AUC increase by coadministration of standard drugs". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 46 (8): 681–96. doi:10.2165/00003088-200746080-00005. PMID 17655375.

- Edoute Y, Nagachandran P, Svirski B, Ben-Ami H (April 2000). "Cardiovascular adverse drug reaction associated with combined beta-adrenergic and calcium entry-blocking agents". Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 35 (4): 556–9. doi:10.1097/00005344-200004000-00007. PMID 10774785.

- Narimatsu A, Taira N (August 1976). "Effects of atrio-ventricular conduction of calcium-antagonistic coronary vasodilators, local anaesthetics and quinidine injected into the posterior and the anterior septal artery of the atrio-ventricular node preparation of the dog". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 294 (2): 169–77. doi:10.1007/bf00507850. PMID 1012337.

- "Drug interactions: Interactions between fentanyl and drugs that inhibit CYP3A4".

- O'Connor SE, Grosset A, Janiak P (1999). "The pharmacological basis and pathophysiological significance of the heart rate-lowering property of diltiazem". Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology. 13 (2): 145–53. doi:10.1111/j.1472-8206.1999.tb00333.x. PMID 10226758.

- Gordon SG, Kittleson MD (2008). "Drugs used in the management of heart disease and cardiac arrhythmias". Small Animal Clinical Pharmacology. Elsevier. pp. 380–457. doi:10.1016/b978-070202858-8.50019-1. ISBN 978-0-7020-2858-8.

- Montastruc JL, Senard JM (April 1992). "[Calcium channel blockers and prevention of migraine]" [Calcium channel blockers and prevention of migraine]. Pathologie-Biologie (in French). 40 (4): 381–8. PMID 1353873.

- Kim KE (February 1991). "Comparative clinical pharmacology of calcium channel blockers". American Family Physician. 43 (2): 583–8. PMID 1990741.

- Andersson KE, Vinge E (March 1990). "Beta-adrenoceptor blockers and calcium antagonists in the prophylaxis and treatment of migraine". Drugs. 39 (3): 355–73. doi:10.2165/00003495-199039030-00003. PMID 1970289.

- Paterna S, Martino SG, Campisi D, Cascio Ingurgio N, Marsala BA (July 1990). "[Evaluation of the effects of verapamil, flunarizine, diltiazem, nimodipine and placebo in the prevention of hemicrania. A double-blind randomized cross-over study]". La Clinica Terapeutica. 134 (2): 119–25. PMID 2147612.

- Smith R, Schwartz A (May 1984). "Diltiazem prophylaxis in refractory migraine". The New England Journal of Medicine. 310 (20): 1327–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM198405173102015. PMID 6144044.

- Peroutka SJ (November 1983). "The pharmacology of calcium channel antagonists: a novel class of anti-migraine agents?". Headache. 23 (6): 278–83. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1983.hed2306278.x. PMID 6358127.

- Common Heart Drug May Reduce Cocaine Cravings. Sciencedaily.com (2008-02-28). Retrieved on 2012-10-21.

- Mills K, Ansah TA, Ali SF, Mukherjee S, Shockley DC (July 2007). "Augmented behavioral response and enhanced synaptosomal calcium transport induced by repeated cocaine administration are decreased by calcium channel blockers". Life Sciences. 81 (7): 600–8. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2007.06.028. PMC 2765982. PMID 17689567.

- Kishioka S, Ko MC, Woods JH (May 2000). "Diltiazem enhances the analgesic but not the respiratory depressant effects of morphine in rhesus monkeys". European Journal of Pharmacology. 397 (1): 85–92. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(00)00248-X. PMID 10844102.

- Verma V, Mediratta PK, Sharma KK (July 2001). "Potentiation of analgesia and reversal of tolerance to morphine by calcium channel blockers". Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 39 (7): 636–42. PMID 12019755.

- Jonas M, Neal KR, Abercrombie JF, Scholefield JH (August 2001). "A randomized trial of oral vs. topical diltiazem for chronic anal fissures". Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 44 (8): 1074–8. doi:10.1007/BF02234624. PMID 11535842.

- Nash GF, Kapoor K, Saeb-Parsy K, Kunanadam T, Dawson PM (November 2006). "The long-term results of diltiazem treatment for anal fissure". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 60 (11): 1411–3. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.00895.x. PMID 16911570.

- Sajid MS, Rimple J, Cheek E, Baig MK (January 2008). "The efficacy of diltiazem and glyceryltrinitrate for the medical management of chronic anal fissure: a meta-analysis". International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 23 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1007/s00384-007-0384-x. PMID 17846781.