Digit (anatomy)

A digit is one of several most distal parts of a limb, such as fingers or toes, present in many vertebrates.

Names

Some languages have different names for hand and foot digits (English: respectively "finger" and "toe", German: "Finger" and "Zeh", French: "doigt" and "orteil").

In other languages, e.g. Russian, Polish, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Czech, Tagalog, Turkish, Bulgarian, and Persian, there are no specific one-word names for fingers and toes; these are called "digit of the hand" or "digit of the foot" instead.

Human digits

Humans normally have five digits on each extremity. Each digit is formed by several bones called phalanges, surrounded by soft tissue. Human fingers normally have a nail at the distal phalanx. The phenomenon of polydactyly occurs when extra digits are present; the utility of such a mutation is case-dependent.[1]

| Fingers | Thumb | Index | Middle | Ring | Little |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toes | Hallux | Long | Third | Fourth | Fifth |

Brain representation

Each finger has an orderly somatotopic representation on the cerebral cortex in the somatosensory cortex area 3b,[2] part of area 1[3] and a distributed, overlapping representation in the supplementary motor area and primary motor area.[4]

The somatosensory cortex representation of the hand is a dynamic reflection of the fingers on the external hand: in syndactyly people have a clubhand of webbed, shortened fingers. However, not only are the fingers of their hands fused, but the cortical maps of their individual fingers also form a club hand. The fingers can be surgically divided to make a more useful hand. Surgeons did this at the Institute of Reconstructive Plastic Surgery in New York to a 32-year-old man with the initials O. G.. They touched O. G.’s fingers before and after surgery while using MRI brain scans. Before the surgery, the fingers mapped onto his brain were fused close together; afterward, the maps of his individual fingers did indeed separate and take the layout corresponding to a normal hand.[5]

Evolution

Two ideas about the homology of arms, hands, and digits exist.

(1) Digits are unique to tetrapods.[6][7]

(2) Antecedents were present in the fins of early sarcopterygian fish.[8]

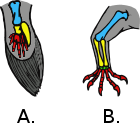

However, 2008 research which created a three-dimensional reconstruction of a Panderichthys, a coastal fish from the Devonian period 385 million years ago, shows that these animals already had many of the homologous bones present in the forelimbs of limbed vertebrates.[9] For example, they had fin radials, bones similar to rudimentary fingers but positioned in the arm-like base of their fins.[9] Thus there was in the evolution of tetrapods a shift such that the outermost part of the fins were lost and came to be replaced by early digits. This change is consistent with additional evidence from the study of actinopterygians, sharks and lungfish that the digits of tetrapods arose from pre-existing distal radials present in more primitive fish.[9][10]

Controversy still exists since Tiktaalik, a vertebrate often considered to be the missing link between fishes and land-living animals, had stubby leg-like limbs that lacked the finger-like radial bones found in the Panderichthys. The researchers of the paper commented that "It is difficult to say whether this character distribution implies that Tiktaalik is autapomorphic, that Panderichthys and tetrapods are convergent, or that Panderichthys is closer to tetrapods than Tiktaalik. At any rate, it demonstrates that the fish–tetrapod transition was accompanied by significant character incongruence in functionally important structures."[9]p. 638.

Bird and theropod dinosaur digits

Birds and theropod dinosaurs (from which birds evolved) have three digits on their hands. Paradoxically the two digits that are missing are different: the bird hand (embedded in the wing) is thought to derive from the second, third and fourth digits of the ancestral five-digit hand. In contrast, the theropod dinosaurs seem to have the first, second and third digits. Recently a Jurassic theropod intermediate fossil Limusaurus has been found in the Junggar Basin in western China that has a complex mix: it has a first digit stub and full second, third and fourth digits but its wrist bones are like those that are associated with the second, third and fourth digits while its finger bones are those of the first, second and third digits.[11] This suggests the evolution of digits in birds resulted from a "shift in digit identity characterized early stages of theropod evolution"[11]

See also

- Polydactyly in early tetrapods

- Polydactyly

Notes

- Dwight T (1892). "Fusion of hands". Memoirs of the Boston Society of Natural History. 4: 473–486.

- Van Westen D, Fransson P, Olsrud J, Rosén B, Lundborg G, Larsson EM (2004). "Fingersomatotopy in area 3b: an fMRI-study". BMC Neurosci. 5: 28. doi:10.1186/1471-2202-5-28. PMC 517711. PMID 15320953.

- Nelson AJ, Chen R (2008). "Digit somatotopy within cortical areas of the postcentral gyrus in humans". Cereb Cortex. 18 (10): 2341–51. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhm257. PMID 18245039.

- Kleinschmidt A, Nitschke MF, Frahm J (1997). "Somatotopy in the human motor cortex hand area. A high-resolution functional MRI study". Eur J Neurosci. 9 (10): 2178–86. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01384.x. PMID 9421177.

- Mogilner A, Grossman JA, Ribary U, Joliot M, Volkmann J, Rapaport D, Beasley RW, Llinás RR (1993). "Somatosensory cortical plasticity in adult humans revealed by magnetoencephalography". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 90 (8): 3593–7. Bibcode:1993PNAS...90.3593M. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.8.3593. PMC 46347. PMID 8386377.

- Holmgren N. (1933). On the origin of the tetrapod limb. Acta Zoologica 14, 185–295.

- Vorobyeva EI (1992). "The role of development and function in formation of tetrapod like pectoral fins". Zh. Obshch. Biol. 53: 149–158.

- Watson DMS (1913). "On the primitive tetrapod limb". Anat. Anzeiger. 44: 24–27.

- Boisvert CA, Mark-Kurik E, Ahlberg PE (2008). "The pectoral fin of Panderichthys and the origin of digits". Nature. 456 (7222): 636–8. Bibcode:2008Natur.456..636B. doi:10.1038/nature07339. PMID 18806778.

- Than, Ker (September 24, 2008). "Ancient Fish Had Primitive Fingers, Toes". National Geographic News.

- Xu Xing; et al. (2009). "A Jurassic ceratosaur from China helps clarify avian digital homologies" (PDF). Nature. 459 (7249): 940–944. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..940X. doi:10.1038/nature08124. PMID 19536256.