Diaphragm pacing

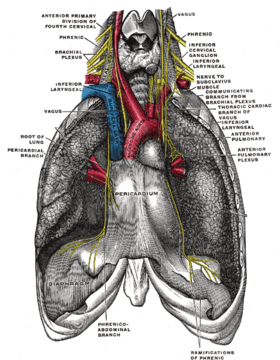

Diaphragm pacing, (and even earlier as electrophrenic respiration[1][2]), is the rhythmic application of electrical impulses to the diaphragm to provide ventilatory support for respiratory failure or sleep apnea.[3][4] Historically, this has been accomplished through the electrical stimulation of a phrenic nerve by an implanted receiver/electrode,[5] though today an alternative option of attaching percutaneous wires to the diaphragm exists.[6]

| Diaphragm pacing | |

|---|---|

Electrical stimulation of the phrenic nerve has been known to stimulate respiration for centuries. | |

| Other names | phrenic nerve pacing |

History

The idea of stimulating the diaphragm through the phrenic nerve was first firmly postulated by German physician Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland, who in 1783 proposed that such a technique could be applied as a treatment for asphyxia.[7][8]:545–549 French neurologist Duchenne de Boulogne made a similar proposal in 1855, though neither of them tested it.[9] It wasn't until a year later that Hugo Wilhelm von Ziemssen demonstrated diaphragm pacing on a 27-year-old woman asphyxiated on charcoal fumes by rhythmically faradizing her phrenic nerves, saving her life.[8][10]:49 Duchenne would later in 1872 declare the technique the "best means of imitating natural respiration".[11] However, advances in mechanical ventilation by the likes of George Poe in the early twentieth century[12] ended up being initially favored over phrenic nerve stimulation.

Harvard researchers Sarnoff et al. revisited diaphragm pacing via the phrenic nerve in 1948, publishing their experimental results on dogs.[1] In a separate publication a few days before, the same group also revealed they had an opportunity to use the technique "on a five-year-old boy with complete respiratory paralysis following rupture of a cerebral aneurysm". Referring to the process as "electrophrenic respiration", Sarnoff was able to artificially respirate the young boy for 52 hours.[13] The technology behind diaphragm pacing was advanced further in 1968 with the publication of doctors John P. Judson and William W. L. Glenn's research on the use of radio-frequency transmission to at whim "adjust the amplitude of stimulation, and to control the rate of stimulation externally".[14] Teaming up with Avery Laboratories, Glenn brought his prototype device to commercial market in the early 1970s.[15] The Avery Breathing Pacemaker received pre-market approval from the FDA in 1987 for “chronic ventilatory support because of upper motor neuron respiratory muscle paralysis” in patients of all ages.[16] In the 1980s, “sequential multipole stimulation” was developed in Tampere, Finland. This technology was commercialized as the Atrostim PNS system and became commercially available in Europe in 1990.[17]

By the early 1990s, long-term evaluations of the technology were being published, with some researchers such as Bach and O'Connor stating that phrenic nerve pacing is a valid option "for the properly screened patient but that expense, failure rate, morbidity and mortality remain excessive and that alternative methods of ventilatory support should be explored".[18] Others such as Brouillette and Marzocchi suggested that advances in encapsulation and electrode technologies could improve system longevity and reduce damage to diaphragm muscle.[19] Additionally, new surgical techniques such as a thoracoscopic approach began to appear in the late 1990s.[20]

In the mid-2000s, U.S. company Synapse Biomedical began researching a new diaphragm pacing system that wouldn't have to attach to the phrenic nerve but instead depended on "four electrodes implanted in the muscle of the diaphragm to electronically stimulate contraction". The marketed NeuRx device received several FDA approvals under a Humanitarian Device Exemption (HDE), one in 2008 and another in 2011.[21]

Methodology and devices

The basic principle behind a diaphragm pacing device (the U.S. Food and Drug Administration identifies the device as a "diaphragmatic/phrenic nerve stimulator"[22]) involves passing an electric current through electrodes that are attached internally. The diaphragm contracts, expanding the chest cavity, causing air to be sucked into the lungs (inspiration). When not stimulated, the diaphragm relaxes and air moves out of the lungs (expiration).

According to the United States Medicare system, phrenic nerve stimulators are indicated for "selected patients with partial or complete respiratory insufficiency" and "can be effective only if the patient has an intact phrenic nerve and diaphragm".[23] Common patient diagnoses for phrenic nerve pacing include patients with spinal cord injury, central sleep apnea, congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (i.e., Ondine's curse), and diaphragm paralysis.[21][23]

There are currently three commercially distributed diaphragm pacing devices: Synapse Biomedical, Inc.'s NeuRx (US), Avery Biomedical Devices, Inc.'s Mark IV Breathing Pacemaker (US),[21] and Atrotech OY's Atrostim PNS (Finland).[24] The Synapse and Avery devices are distributed worldwide and approved for use in the United States.[21] The Atrotech device is not available in the U.S. As of December of 2019, FDA Premarket Approval was given to Avery's Spirit Transmitter Device, replacing the Mark IV transmitter. [25]

Surgical procedure

In the case of the Atrostim and Mark IV devices, several surgical techniques may be used. Surgery is typically performed by placing an electrode around the phrenic nerve, either in the neck (i.e., cervically; an older technique), or in the chest (i.e., thoracically; more modern). This electrode is connected to a radiofrequency receiver which is implanted just under the skin. An external transmitter sends radio signals to the device by an antenna which is worn over the receiver.[26] For the cervical surgical technique, the phrenic nerve is approached via a small (~5 cm) incision slightly above, and midline to, the clavic. The phrenic nerve is then isolated under the scalenus anticus muscle. For the thoracic surgical technique, a small (~5 cm) incisions over the 2nd or 3rd intercostal space. The electrodes are placed around the phrenic nerves alongside the pericardium. Use of a thorascope allows for this technique to be performed in a minimally-invasive manner.[26]

In the case of the NeuRx device, a series of four incisions are made in the abdominal skin. Several tools such as a laparoscope and probe are used to find the best four locations on the diaphragm to attach four electrodes, which have connections outside the body. A fifth electrode is placed just under the skin in the same area. All these connect to the device.[27]

References

- Sarnoff, S.J.; Whittenberger, J.L.; Hardenbergh, E. (1948). "Electrophrenic respiration. Mechanism of the inhibition of spontaneous respiration". American Journal of Physiology. 155 (2): 203–207. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1948.155.2.203. PMID 18107083.

- Marshall, L.B., ed. (1951). "Electrophrenic Respiration". United States Navy Medical News Letter. 18 (4): 10–12.

- Bhimji, S. (16 December 2015). Mosenifar, Z. (ed.). "Overview - Indications and Contraindications". Medscape - Diaphragm Pacing. WebMD LLC. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- Khanna, V.K. (2015). "Chapter 19: Diaphragmatic/Phrenic Nerve Stimulation". Implantable Medical Electronics: Prosthetics, Drug Delivery, and Health Monitoring. Springer International Publishing AG Switzerland. p. 453. ISBN 9783319254487. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- Chen, M.L; Tablizo, M.A.; Kun, S.; Keens, T.G. (2005). "Diaphragm pacers as a treatment for congenital central hypoventilation syndrome". Expert Review of Medical Devices. 2 (5): 577–585. doi:10.1586/17434440.2.5.577. PMID 16293069.

- "Use and Care of the NeuRx Diaphragm Pacing System" (PDF). Synapse Biomedical, Inc. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- Hufeland, C.W. (1783). Usum uis electriciae in asphyxia experimentis illustratum. Dissertatio inauguralis medica sistens.

- Althaus, Julius (1870). A Treatise on Medical Electricity, Theoretical and Practical: And Its Use in the Treatment of Paralysis, Neuralgia and Other Diseases (2nd ed.). London: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 676. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- Duchenne, G.B.A. (1855). De l'electrisation localisée et de son application a la physiologie, a la pathologie et a la thérapeutique. Paris: Baillière. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- von Ziemssen, H.W. (1857). Die Electricität in der Medicin Studien. Berlin: Hirschwald. p. 106. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- Duchenne, G.B.A. (1872). De l'électrisation localisée et de son application à la pathologie et à la thérapeutique par courants induits et par courants galvaniques interrompus et continus. Paris: Baillière. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- "Smother Small Dog To See it Revived". The New York Times. 29 May 1908. Retrieved 19 February 2016 – via WikiMedia Commons.

- Sarnoff, S.J.; Hardenbergh, E.; Whittenberger, J.L. (1948). "Electrophrenic Respiration". Science. 108 (2809): 482. Bibcode:1948Sci...108..482S. doi:10.1126/science.108.2809.482.

- Judson, J.P.; Glenn, W.W.L. (1968). "Radio-Frequency electrophrenic respiration: Long-term application to a patient with primary hypoventilation". JAMA. 203 (12): 1033–1037. doi:10.1001/jama.1968.03140120031007. PMID 5694362.

- "History of Pacing". Avery Biomedical Devices, Inc. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- Wang, Diep (June 2015). "Diaphragm Pacing without Tracheostomy in Congenital Central Hypoventilation Syndrome Patients". Respiration. 89 (6). Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- "Phrenic Nerve Stimulation". Atrotech. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Bach, J.R.; O'Connor, K. (1991). "Electrophrenic ventilation: A different perspective". The Journal of the American Paraplegia Society. 14 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1080/01952307.1991.11735829. PMID 2022962.

- Brouillette, R.T.; Marzocchi, M. (1994). "Diaphragm pacing: clinical and experimental results". Biology of the Neonate. 65 (3–4): 265–271. doi:10.1159/000244063. PMID 8038293.

- Shaul, D.B.; Danielson, P.D.; McComb, J.G.; Keens, T.G. (2002). "Thoracoscopic placement of phrenic nerve electrodes for diaphragmatic pacing in children". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 37 (7): 974–978. doi:10.1053/jpsu.2002.33821. PMID 12077752.

- "Diaphragmatic/Phrenic Nerve Stimulation and Diaphragm Pacing Systems". Policy # MED.00100. Anthem Insurance Companies, Inc. 5 February 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- "PART 882 -- NEUROLOGICAL DEVICES". CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 21 August 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- "Chapter 1, Part 2, Section 160.19: Phrenic Nerve Stimulator" (PDF). Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- "Phrenic Nerve Stimulation". Atrotech OY. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- "Premarket Approval". fda.gov. US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Bhimji, S. (16 December 2015). Mosenifar, Z. (ed.). "Technique - Insertion of Pacemaker". Medscape - Diaphragm Pacing. WebMD LLC. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- "Surgery: What to Expect" (PDF). NeuRx Diaphragm Pacing System Patient/Caregiver Information and Instruction Manual. Synapse Biomedical, Inc. 2011. p. 18. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

Further reading

- Bhimji, S. (16 December 2015). Mosenifar, Z. (ed.). "Diaphragm Pacing". Medscape. WebMD LLC.

- Khanna, V.K. (2015). "Chapter 19: Diaphragmatic/Phrenic Nerve Stimulation". Implantable Medical Electronics: Prosthetics, Drug Delivery, and Health Monitoring. Springer International Publishing AG Switzerland. p. 453. ISBN 9783319254487.