Defibrillation

Defibrillation is a treatment for life-threatening cardiac dysrhythmias, specifically ventricular fibrillation (VF) and non-perfusing ventricular tachycardia (VT).[1][2] A defibrillator delivers a dose of electric current (often called a counter-shock) to the heart. Although not fully understood, this process depolarizes a large amount of the heart muscle, ending the dysrhythmia. Subsequently, the body's natural pacemaker in the sinoatrial node of the heart is able to re-establish normal sinus rhythm.[3]

| Defibrillation | |

|---|---|

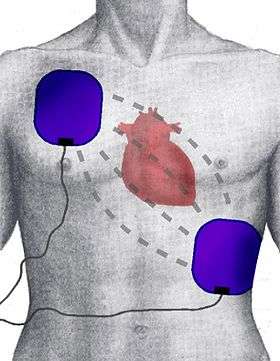

View of defibrillator electrode position and placement. |

In contrast to defibrillation, synchronized electrical cardioversion is an electrical shock delivered in synchrony to the cardiac cycle.[4] Although the person may still be critically ill, cardioversion normally aims to end poorly perfusing cardiac dysrhythmias, such as supraventricular tachycardia.[1][2]

Defibrillators can be external, transvenous, or implanted (implantable cardioverter-defibrillator), depending on the type of device used or needed.[5] Some external units, known as automated external defibrillators (AEDs), automate the diagnosis of treatable rhythms, meaning that lay responders or bystanders are able to use them successfully with little or no training.[2]

Medical uses

Defibrillation is often an important step in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).[6][7] CPR is an algorithm-based intervention aimed to restore cardiac and pulmonary function.[6] Defibrillation is indicated only in certain types of cardiac dysrhythmias, specifically ventricular fibrillation (VF) and pulseless ventricular tachycardia.[1][2] If the heart has completely stopped, as in asystole or pulseless electrical activity (PEA), defibrillation is not indicated. Defibrillation is also not indicated if the patient is conscious or has a pulse. Improperly given electrical shocks can cause dangerous dysrhythmias, such as ventricular fibrillation.[1]

Survival rates for out-of-hospital cardiac arrests are poor, often less than 10%.[8] Outcome for in-hospital cardiac arrests are higher at 20%.[8] Within the group of people presenting with cardiac arrest, the specific cardiac rhythm can significantly impact survival rates. Compared to people presenting with a non-shockable rhythm (such as asystole or PEA), people with a shockable rhythm (such as VF or pulseless ventricular tachycardia) have improved survival rates, ranging between 21-50%.[6][9][10]

Types

Manual external defibrillator

Manual external defibrillators require the expertise of a healthcare professional.[11][12] They are used in conjunction with an electrocardiogram, which can be separate or built-in. A healthcare provider first diagnose the cardiac rhythm and then manually determine the voltage and timing for the electrical shock. These units are primarily found in hospitals and on some ambulances. For instance, every NHS ambulance in the United Kingdom is equipped with a manual defibrillator for use by the attending paramedics and technicians. In the United States, many advanced EMTs and all paramedics are trained to recognize lethal arrhythmias and deliver appropriate electrical therapy with a manual defibrillator when appropriate.

Manual internal defibrillator

Manual internal defibrillators deliver the shock through paddles placed directly on the heart.[1] They are mostly used in the operating room and, in rare circumstances, in the emergency room during an open heart procedure.

Automated external defibrillator (AED)

Automated external defibrillators are designed for use by untrained or briefly trained laypersons.[13][14][15] AEDs contain technology for analysis of heart rhythms. As a result, it does not require a trained health provider to determine whether or not a rhythm is shockable. By making these units publicly available, AEDs have improved outcomes for sudden out-of-hospital cardiac arrests.[13][14]

Trained health professionals have more limited use for AEDs than manual external defibrillators.[16] Recent studies show that AEDs does not improve outcome in patients with in-hospital cardiac arrests.[16][17] AEDs have set voltages and does not allow the operator to vary voltage according to need. AEDs may also delay delivery of effective CPR. For diagnosis of rhythm, AEDs often require the stopping of chest compressions and rescue breathing. For these reasons, certain bodies, such as the European Resuscitation Council, recommend using manual external defibrillators over AEDs if manual external defibrillators are readily available.[17]

As early defibrillation can significantly improve VF outcomes, AEDs have become publicly available in many easily accessible areas.[16][17] AEDs have been incorporated into the algorithm for basic life support (BLS). Many first responders, such as firefighters, policemen, and security guards, are equipped with them.

AEDs can be fully automatic or semi-automatic.[18] A semi-automatic AED automatically diagnoses heart rhythms and determines if a shock is necessary. If a shock is advised, the user must then push a button to administer the shock. A fully automated AED automatically diagnoses the heart rhythm and advises the user to stand back while the shock is automatically given. Some types of AEDs come with advanced features, such as a manual override or an ECG display.

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

Also known as automatic internal cardiac defibrillator (AICD). These devices are implants, similar to pacemakers (and many can also perform the pacemaking function). They constantly monitor the patient's heart rhythm, and automatically administer shocks for various life-threatening arrhythmias, according to the device's programming. Many modern devices can distinguish between ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, and more benign arrhythmias like supraventricular tachycardia and atrial fibrillation. Some devices may attempt overdrive pacing prior to synchronised cardioversion. When the life-threatening arrhythmia is ventricular fibrillation, the device is programmed to proceed immediately to an unsynchronized shock.

There are cases where the patient's ICD may fire constantly or inappropriately. This is considered a medical emergency, as it depletes the device's battery life, causes significant discomfort and anxiety to the patient, and in some cases may actually trigger life-threatening arrhythmias. Some emergency medical services personnel are now equipped with a ring magnet to place over the device, which effectively disables the shock function of the device while still allowing the pacemaker to function (if the device is so equipped). If the device is shocking frequently, but appropriately, EMS personnel may administer sedation.

Wearable cardioverter defibrillator

A wearable cardioverter defibrillator is a portable external defibrillator that can be worn by at-risk patients.[19] The unit monitors the patient 24 hours a day and can automatically deliver a biphasic shock if VF or VT is detected. This device is mainly indicated in patients who are not immediate candidates for ICDs.[20]

Internal defibrillator

This is often used to defibrillate the heart during or after cardiac surgery such as a heart bypass. The electrodes consist of round metal plates that come in direct contact with the myocardium.

Interface with person

The connection between the defibrillator and the patient consists of a pair of electrodes, each provided with electrically conductive gel in order to ensure a good connection and to minimize electrical resistance, also called chest impedance (despite the DC discharge) which would burn the patient. Gel may be either wet (similar in consistency to surgical lubricant) or solid (similar to gummi candy). Solid-gel is more convenient, because there is no need to clean the used gel off the person's skin after defibrillation. However, the use of solid-gel presents a higher risk of burns during defibrillation, since wet-gel electrodes more evenly conduct electricity into the body. Paddle electrodes, which were the first type developed, come without gel, and must have the gel applied in a separate step. Self-adhesive electrodes come prefitted with gel. There is a general division of opinion over which type of electrode is superior in hospital settings; the American Heart Association favors neither, and all modern manual defibrillators used in hospitals allow for swift switching between self-adhesive pads and traditional paddles. Each type of electrode has its merits and demerits.

Paddle electrodes

The most well-known type of electrode (widely depicted in films and television) is the traditional metal paddle with an insulated (usually plastic) handle. This type must be held in place on the patient's skin with approximately 25 lbs of force while a shock or a series of shocks is delivered. Paddles offer a few advantages over self-adhesive pads. Many hospitals in the United States continue the use of paddles, with disposable gel pads attached in most cases, due to the inherent speed with which these electrodes can be placed and used. This is critical during cardiac arrest, as each second of nonperfusion means tissue loss. Modern paddles allow for monitoring (electrocardiography), though in hospital situations, separate monitoring leads are often already in place.

Paddles are reusable, being cleaned after use and stored for the next patient. Gel is therefore not preapplied, and must be added before these paddles are used on the patient. Paddles are generally only found on manual external units.

Self-adhesive electrodes

Newer types of resuscitation electrodes are designed as an adhesive pad, which includes either solid or wet gel. These are peeled off their backing and applied to the patient's chest when deemed necessary, much the same as any other sticker. The electrodes are then connected to a defibrillator, much as the paddles would be. If defibrillation is required, the machine is charged, and the shock is delivered, without any need to apply any additional gel or to retrieve and place any paddles. Most adhesive electrodes are designed to be used not only for defibrillation, but also for transcutaneous pacing and synchronized electrical cardioversion. These adhesive pads are found on most automated and semi-automated units and are replacing paddles entirely in non-hospital settings. In hospital, for cases where cardiac arrest is likely to occur (but has not yet), self-adhesive pads may be placed prophylactically.

Pads also offer an advantage to the untrained user, and to medics working in the sub-optimal conditions of the field. Pads do not require extra leads to be attached for monitoring, and they do not require any force to be applied as the shock is delivered. Thus, adhesive electrodes minimize the risk of the operator coming into physical (and thus electrical) contact with the patient as the shock is delivered by allowing the operator to be up to several feet away. (The risk of electrical shock to others remains unchanged, as does that of shock due to operator misuse.) Self-adhesive electrodes are single-use only. They may be used for multiple shocks in a single course of treatment, but are replaced if (or in case) the patient recovers then reenters cardiac arrest.

Placement

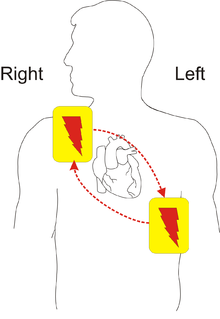

Resuscitation electrodes are placed according to one of two schemes. The anterior-posterior scheme is the preferred scheme for long-term electrode placement. One electrode is placed over the left precordium (the lower part of the chest, in front of the heart). The other electrode is placed on the back, behind the heart in the region between the scapula. This placement is preferred because it is best for non-invasive pacing.

The anterior-apex scheme can be used when the anterior-posterior scheme is inconvenient or unnecessary. In this scheme, the anterior electrode is placed on the right, below the clavicle. The apex electrode is applied to the left side of the patient, just below and to the left of the pectoral muscle. This scheme works well for defibrillation and cardioversion, as well as for monitoring an ECG.

Researchers have created a software modeling system capable of mapping an individual's chest and determining the best position for an external or internal cardiac defibrillator.[21]

Mechanism of action

The exact mechanism of defibrillation is not well understood.[2][22] One theory is that successful defibrillation affects most of the heart, resulting in insufficient remaining heart muscle to continue the arrhythmia.[2] Recent mathematical models of defibrillation are providing new insight into how cardiac tissue responds to a strong electrical shock.[22]

History

Defibrillators were first demonstrated in 1899 b Jean-Louis Prévost and Frédéric Batelli, two physiologists from University of Geneva, Switzerland. They discovered that small electrical shocks could induce ventricular fibrillation in dogs, and that larger charges would reverse the condition.[23][24]

In 1933, Dr. Albert Hyman, heart specialist at the Beth Davis Hospital of New York City and C. Henry Hyman, an electrical engineer, looking for an alternative to injecting powerful drugs directly into the heart, came up with an invention that used an electrical shock in place of drug injection. This invention was called the Hyman Otor where a hollow needle is used to pass an insulated wire to the heart area to deliver the electrical shock. The hollow steel needle acted as one end of the circuit and the tip of the insulated wire the other end. Whether the Hyman Otor was a success is unknown.[25]

The external defibrillator as known today was invented by Electrical Engineer William Kouwenhoven in 1930. William studied the relation between the electric shocks and its effects on human heart when he was a student at Johns Hopkins University School of Engineering. His studies helped him to invent a device for external jump start of the heart. He invented the defibrillator and tested on a dog, like Prévost and Batelli. The first use on a human was in 1947 by Claude Beck,[26] professor of surgery at Case Western Reserve University. Beck's theory was that ventricular fibrillation often occurred in hearts which were fundamentally healthy, in his terms "Hearts that are too good to die", and that there must be a way of saving them. Beck first used the technique successfully on a 14-year-old boy who was being operated on for a congenital chest defect. The boy's chest was surgically opened, and manual cardiac massage was undertaken for 45 minutes until the arrival of the defibrillator. Beck used internal paddles on either side of the heart, along with procainamide, an antiarrhythmic drug, and achieved return of a perfusing cardiac rhythm.

These early defibrillators used the alternating current from a power socket, transformed from the 110–240 volts available in the line, up to between 300 and 1000 volts, to the exposed heart by way of "paddle" type electrodes. The technique was often ineffective in reverting VF while morphological studies showed damage to the cells of the heart muscle post mortem. The nature of the AC machine with a large transformer also made these units very hard to transport, and they tended to be large units on wheels.

Closed-chest method

Until the early 1950s, defibrillation of the heart was possible only when the chest cavity was open during surgery. The technique used an alternating voltage from a 300 or greater volt source derived from standard AC power, delivered to the sides of the exposed heart by "paddle" electrodes where each electrode was a flat or slightly concave metal plate of about 40 mm diameter. The closed-chest defibrillator device which applied an alternating voltage of greater than 1000 volts, conducted by means of externally applied electrodes through the chest cage to the heart, was pioneered by Dr V. Eskin with assistance by A. Klimov in Frunze, USSR (today known as Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan) in the mid-1950s.[27] The duration of AC shocks was typically in the range of 100-150 milliseconds[28]

Direct current method

Early successful experiments of successful defibrillation by the discharge of a capacitor performed on animals were reported by N. L. Gurvich and G. S. Yunyev in 1939.[29] In 1947 their works were reported in western medical journals.[30] Serial production of Gurvich's pulse defibrillator started in 1952 at the electromechanical plant of the institute, and was designated model ИД-1-ВЭИ (Импульсный Дефибриллятор 1, Всесоюзный Электротехнический Институт, or in English, Pulse Defibrillator 1, All-Union Electrotechnical Institute). It is described in detail in Gurvich's 1957 book, Heart Fibrillation and Defibrillation.[31]

The first Czechoslovak "universal defibrillator Prema" was manufactured in 1957 by the company Prema, designed by dr. Bohumil Peleška. In 1958 his device was awarded Grand Prix at Expo 58.[32]

In 1958, US senator Hubert H. Humphrey visited Nikita Khrushchev and among other things he visited the Moscow Institute of Reanimatology, where, among others, he met with Gurvich.[33] Humphrey immediately recognized importance of reanimation research and after that a number of American doctors visited Gurvich. At the same time, Humphrey worked on establishing of a federal program in the National Institute of Health in physiology and medicine, telling to the Congress: "Let's compete with U.S.S.R. in research on reversibility of death".[34]

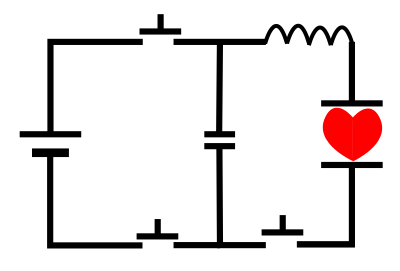

In 1959 Bernard Lown commenced research in his animal laboratory in collaboration with engineer Barouh Berkovits into a technique which involved charging of a bank of capacitors to approximately 1000 volts with an energy content of 100-200 joules then delivering the charge through an inductance such as to produce a heavily damped sinusoidal wave of finite duration (~5 milliseconds) to the heart by way of paddle electrodes. This team further developed an understanding of the optimal timing of shock delivery in the cardiac cycle, enabling the application of the device to arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, and supraventricular tachycardias in the technique known as "cardioversion".

The Lown-Berkovits waveform, as it was known, was the standard for defibrillation until the late 1980s. Earlier in the 1980s, the "MU lab" at the University of Missouri had pioneered numerous studies introducing a new waveform called a biphasic truncated waveform (BTE). In this waveform an exponentially decaying DC voltage is reversed in polarity about halfway through the shock time, then continues to decay for some time after which the voltage is cut off, or truncated. The studies showed that the biphasic truncated waveform could be more efficacious while requiring the delivery of lower levels of energy to produce defibrillation.[28] An added benefit was a significant reduction in weight of the machine. The BTE waveform, combined with automatic measurement of transthoracic impedance is the basis for modern defibrillators.

Portable units become available

A major breakthrough was the introduction of portable defibrillators used out of the hospital. Already Peleška's Prema defibrillator was designed to be more portable than original Gurvich's model. In Soviet Union, a portable version of Gurvich's defibrillator, model ДПА-3 (DPA-3), was reported in 1959.[35] In the west this was pioneered in the early 1960s by Prof. Frank Pantridge in Belfast. Today portable defibrillators are among the many very important tools carried by ambulances. They are the only proven way to resuscitate a person who has had a cardiac arrest unwitnessed by Emergency Medical Services (EMS) who is still in persistent ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia at the arrival of pre-hospital providers.

Gradual improvements in the design of defibrillators, partly based on the work developing implanted versions (see below), have led to the availability of Automated External Defibrillators. These devices can analyse the heart rhythm by themselves, diagnose the shockable rhythms, and charge to treat. This means that no clinical skill is required in their use, allowing lay people to respond to emergencies effectively.

Change to a biphasic waveform

Until the mid 90s, external defibrillators delivered a Lown type waveform (see Bernard Lown) which was a heavily damped sinusoidal impulse having a mainly uniphasic characteristic. Biphasic defibrillation alternates the direction of the pulses, completing one cycle in approximately 12 milliseconds. Biphasic defibrillation was originally developed and used for implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. When applied to external defibrillators, biphasic defibrillation significantly decreases the energy level necessary for successful defibrillation, decreasing the risk of burns and myocardial damage.

Ventricular fibrillation (VF) could be returned to normal sinus rhythm in 60% of cardiac arrest patients treated with a single shock from a monophasic defibrillator. Most biphasic defibrillators have a first shock success rate of greater than 90%.[36]

Implantable devices

A further development in defibrillation came with the invention of the implantable device, known as an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (or ICD). This was pioneered at Sinai Hospital in Baltimore by a team that included Stephen Heilman, Alois Langer, Jack Lattuca, Morton Mower, Michel Mirowski, and Mir Imran, with the help of industrial collaborator Intec Systems of Pittsburgh.[37] Mirowski teamed up with Mower and Staewen, and together they commenced their research in 1969 but it was 11 years before they treated their first patient. Similar developmental work was carried out by Schuder and colleagues at the University of Missouri.

The work was commenced, despite doubts amongst leading experts in the field of arrhythmias and sudden death. There was doubt that their ideas would ever become a clinical reality. In 1962 Bernard Lown introduced the external DC defibrillator. This device applied a direct current from a discharging capacitor through the chest wall into the heart to stop heart fibrillation.[38] In 1972, Lown stated in the journal Circulation — "The very rare patient who has frequent bouts of ventricular fibrillation is best treated in a coronary care unit and is better served by an effective antiarrhythmic program or surgical correction of inadequate coronary blood flow or ventricular malfunction. In fact, the implanted defibrillator system represents an imperfect solution in search of a plausible and practical application."[39]

The problems to be overcome were the design of a system which would allow detection of ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia. Despite the lack of financial backing and grants, they persisted and the first device was implanted in February 1980 at Johns Hopkins Hospital by Dr. Levi Watkins, Jr. assisted by Vivien Thomas. Modern ICDs do not require a thoracotomy and possess pacing, cardioversion, and defibrillation capabilities.

The invention of implantable units is invaluable to some regular sufferers of heart problems, although they are generally only given to those people who have already had a cardiac episode.

People can live long normal lives with the devices. Many patients have multiple implants. A patient in Houston, Texas had an implant at the age of 18 in 1994 by the recent Dr. Antonio Pacifico. He was awarded "Youngest Patient with Defibrillator" in 1996. Though today these devices are implanted into small babies shortly after birth.

Society and culture

As devices that can quickly produce dramatic improvements in patient health, defibrillators are often depicted in movies, television, video games and other fictional media. Their function, however, is often exaggerated, with the defibrillator inducing a sudden, violent jerk or convulsion by the patient; in reality, although the muscles may contract, such dramatic patient presentation is rare. Similarly, medical providers are often depicted defibrillating patients with a "flat-line" ECG rhythm (also known as asystole). This is not normal medical practice, as the heart cannot be restarted by the defibrillator itself. Only the cardiac arrest rhythms ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia are normally defibrillated. The purpose of defibrillation is to depolarize the entire heart all at once so that it is synchronized, in the hope that it will resume beating normally. Someone who is already in asystole cannot be helped by electrical means, and usually needs urgent CPR and intravenous medication. There are also several heart rhythms that can be "shocked" when the patient is not in cardiac arrest, such as supraventricular tachycardia and ventricular tachycardia that produces a pulse; this more-complicated procedure is known as cardioversion, not defibrillation.

Trivia

In Australia up until the 1990s it was relatively rare for ambulances to carry defibrillators. This changed in 1990 after Australian media mogul Kerry Packer had a heart attack and, purely by chance, the ambulance that responded to the call carried a defibrillator. After recovering, Kerry Packer donated a large sum to the Ambulance Service of New South Wales in order that all ambulances in New South Wales should be fitted with a personal defibrillator, which is why defibrillators in Australia are sometimes colloquially called "Packer Whackers".[40] Following the widespread introduction of the machines to Ambulances, various Governments have distributed them to local sporting fields.

See also

- Advanced cardiac life support (ACLS)

- Automated external defibrillator

- Ambulance

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)

- Cardioversion

- Myocardial infarction (heart attack)

- Wearable cardioverter defibrillator

References

- Ong, ME; Lim, S; Venkataraman, A (2016). "Defibrillation and cardioversion". In Tintinalli JE; et al. (eds.). Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8e. McGraw-Hill (New York, NY).

- Kerber, RE (2011). "Chapter 46. Indications and Techniques of Electrical Defibrillation and Cardioversion". In Fuster V; Walsh RA; Harrington RA (eds.). Hurst's The Heart (13th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill – via AccessMedicine.

- Werman, Howard A.; Karren, K; Mistovich, Joseph (2014). "Automated External Defibrillation and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation". In Werman A. Howard; Mistovich J; Karren K (eds.). Prehospital Emergency Care, 10e. Pearson Education, Inc. p. 425.

- Author:Bradley P Knight, MD, FACCSection Editor:Richard L Page, MDDeputy Editor:Brian C Downey, MD, FACC. "Basic principles and technique of external electrical cardioversion and defibrillation". UpToDate. Retrieved 2019-07-24.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hoskins, MH; De Lurgio, DB (2012). "Chapter 129. Pacemakers, Defibrillators, and Cardiac Resynchronization Devices in Hospital Medicine". In McKean SC; Ross JJ; Dressler DD; Brotman DJ; Ginsberg JS (eds.). Principles and Practice of Hospital Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill – via Access Medicine.

- Venegas-Borsellino, C; Bangar, MD (2016). "CPR and ACLS Updates". In Orpello JM; et al. (eds.). Critical Care. McGraw-Hill (New York, NY).

- Marenco, JP; Wang, PJ; Link, MS; Homoud, MK; Estes III, NAM (2001). "Improving Survival From Sudden Cardiac ArrestThe Role of the Automated External Defibrillator". JAMA. 285 (9): 1193–1200. doi:10.1001/jama.285.9.1193. PMID 11231750 – via JAMA Network.

- "Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR): Practice Essentials, Preparation, Technique". 2016-11-03. Archived from the original on 2016-12-07. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Nadkarni, Vinay M. (2006-01-04). "First Documented Rhythm and Clinical Outcome From In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Among Children and Adults". JAMA. 295 (1): 50–7. doi:10.1001/jama.295.1.50. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 16391216.

- Nichol, Graham (2008-09-24). "Regional Variation in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Incidence and Outcome". JAMA. 300 (12): 1423–31. doi:10.1001/jama.300.12.1423. ISSN 0098-7484. PMC 3187919. PMID 18812533.

- Beaumont, E (2001). "Teaching Colleagues and the General Public about Automatic External Defibrillators". Medscape. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. Archived from the original on January 23, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Center for Devices and Radiological Health. "External Defibrillators - External Defibrillator Improvement Initiative Paper". www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-11-10. Retrieved 2016-12-08.

- Powell, Judy; Van Ottingham, Lois; Schron, Eleanor (2016-12-01). "Public defibrillation: increased survival from a structured response system". The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 19 (6): 384–389. doi:10.1097/00005082-200411000-00009. ISSN 0889-4655. PMID 15529059.

- Investigators, The Public Access Defibrillation Trial (2004-08-12). "Public-Access Defibrillation and Survival after Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest". New England Journal of Medicine. 351 (7): 637–646. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040566. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 15306665.

- Yeung, Joyce; Okamoto, Deems; Soar, Jasmeet; Perkins, Gavin D. (2011-06-01). "AED training and its impact on skill acquisition, retention and performance--a systematic review of alternative training methods" (PDF). Resuscitation. 82 (6): 657–664. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.02.035. ISSN 1873-1570. PMID 21458137.

- Chan, Paul S.; Krumholz, Harlan M.; Spertus, John A.; Jones, Philip G.; Cram, Peter; Berg, Robert A.; Peberdy, Mary Ann; Nadkarni, Vinay; Mancini, Mary E. (2010-11-17). "Automated external defibrillators and survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest". JAMA. 304 (19): 2129–2136. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1576. ISSN 1538-3598. PMC 3587791. PMID 21078809.

- Perkins, GD; Handley, AJ; Koster, RW; Castren, M; Smyth, T; Monsieurs, KG; Raffay, V; Grasner, JT; Wenzel, V; Ristagno, G; Soar, J (2015). "European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015 Section 2. Adult basic life support and automated external defibrillation" (PDF). Resuscitation. 95: 81–99. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.015. PMID 26477420. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-12-20.

- Physio-Control (2011). "Benefits of Fully Automated Defibrillators" (PDF). Physio-Control. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- "What is the LifeVest?". Zoll Lifecor. Archived from the original on 2008-11-21. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- Adler, Arnon; Halkin, Amir; Viskin, Sami (2013-02-19). "Wearable Cardioverter-Defibrillators". Circulation. 127 (7): 854–860. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.146530. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 23429896.

- Jolley, Matthew; Stinstra, Jeroen; Pieper, Steve; MacLeod, Rob; Brooks, Dana; Cecchin, Frank; Triedman, John (2008). "A Computer Modeling Tool for Comparing Novel ICD Electrode Orientations in Children and Adults". Hearth Rhythm. 5 (4): 565–572. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.01.018. PMC 2745086. PMID 18362024.

- Trayanova N (2006). "Defibrillation of the heart: insights into mechanisms from modelling studies". Experimental Physiology. 91 (2): 323–337. doi:10.1113/expphysiol.2005.030973. PMID 16469820.

- Prevost J.L., Batelli F. (1899). "Some Effects of Electric Discharge on the Hearts of Mammals". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences. 129: 1267–1268.

- Lockyer, Sir Norman (1900). "Restoration of the Functions of the Heart and Central Nervous System after Complete Anemia". Nature. 61: 532.

- Corporation, Bonnier (1 October 1933). "Popular Science". Bonnier Corporation. Retrieved 2 May 2018 – via Google Books.

- "Claude Beck, defibrillation and CPR". Case Western Reserve University. Archived from the original on 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- Sov Zdravookhr Kirg. (1975). "Some results with the use of the DPA-3 defibrillator (developed by V. Ia. Eskin and A. M. Klimov) in the treatment of terminal states". Sovetskoe Zdravookhranenie Kirgizii (in Russian). 66 (4): 23–25. doi:10.1016/0006-291x(75)90518-5. PMID 6.

- "Apparatus for defibrillation or cardioversion with a waveform optimized in the frequency domain". Patents. 21 June 2006. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Гурвич Н.Л., Юньев Г.С. О восстановлении нормальной деятельности фибриллирующего сердца теплокровных посредством конденсаторного разряда // Бюллетень экспериментальной биологии и медицины, 1939, Т. VIII, № 1, С. 55-58

- Gurvich NL, Yunyev GS. Restoration of a regular rhythm in the mammalian fibrillating heart // Am Rev Sov Med. 1946 Feb;3:236-9

- Аппарат для дефибрилляции сердца одиночным электрическим импульсо,м in: Гурвич Н.Л. Фибрилляция и дефибрилляция сердца. Moscow, Medgiz, 1957, pp. 229-233.

- Elektrická kardioverze a defibrilace, Intervenční a akutní kardiologie, 2011; 10(1)

- Humphrey H H. My marathon talk with Russia's boss: Senator Humphrey reports in full on Khrushchev — his threats, jokes, criticism of China's communes New York, Time, Inc., 1959, pp. 80–91.

- Humphrey H.H. "An important phase of world medical research: Let's compete with U.S.S.R. in research on reversibility of death." Congressional Records, October 13, 1962; A7837–A7839

- "П О РТА ТИ ВН Ы Й Д Е Ф И Б Р И Л Л Я Т О Р С У Н И В Е РС А Л Ь Н Ы М ПИТАНИЕМ" Archived 2014-11-29 at the Wayback Machine (Portable defibrillator with universal power supply)

- Heart Smarter: EMS Implications of the 2005 AHA Guidelines for ECC & CPR Archived 2007-06-16 at the Wayback Machine pp 15-16

- Wiley Interscience

- Aston, Richard (1991). Principles of Biomedical Instrumentation and Measurement: International Edition. Merrill Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-02-946562-2.

- Giedwoyn, Jerzy O. (1972). "Pacemaker Failure following External Defibrillation" (PDF). Circulation. 44 (2): 293. doi:10.1161/01.cir.44.2.293. ISSN 1524-4539. PMID 5562564.

- Karl Kruszelnicki (2008-08-08). "Dr Karl's Great Moments In Science, Flatline and defibrillator (Part II)". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 2012-11-10. Retrieved 2011-12-21.

Bibliography

- Picard, André (2007-04-27). "School defibrillators could be a lifesaver". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2015-07-23.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Defibrillator. |

- Sudden Cardiac Arrest Foundation

- Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology

- American Red Cross: Saving a Life is as Easy as A-E-D

- FDA Heart Health Online: Automated External Defibrillator (AED)