Deciduous teeth

Deciduous teeth – commonly known as milk teeth, baby teeth, temporary teeth,[1] and primary teeth – are the first set of teeth in the growth development of humans and other diphyodont mammals. They develop during the embryonic stage of development and erupt (that is, they become visible in the mouth) during infancy. They are usually lost and replaced by permanent teeth, but in the absence of permanent replacements, they can remain functional for many years.

| Deciduous teeth | |

|---|---|

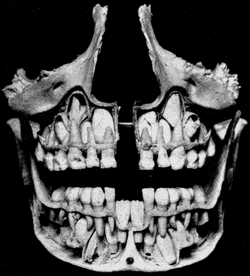

Cross-section, with permanent teeth located above and below the deciduous teeth prior to exfoliation. The deciduous mandibular central incisors have already been exfoliated | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | dentes decidui |

| MeSH | D014094 |

| TA | A05.1.03.076 |

| FMA | 75151 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Development

Formation

Primary teeth start to form during the embryo phase of human life. The development of primary teeth starts at the sixth week of tooth development as the dental lamina. This process starts at the midline and then spreads back into the posterior region. By the time the embryo is eight weeks old, there are ten buds on the upper and lower arches that will eventually become the primary (deciduous) dentition. These teeth will continue to form until they erupt in the mouth. In the primary dentition, there are a total of twenty teeth: five per quadrant and ten per arch. The eruption of these teeth ("teething") begins at the age of six months and continues until 25–33 months of age during the primary dentition period. Usually, the first teeth seen in the mouth are the mandibular centrals and the last are the maxillary second molars.

The primary teeth are made up of central incisors, lateral incisors, canines, first molars, and secondary molars; there is one in each quadrant, making a total of four of each tooth. All of these are gradually replaced with a permanent counterpart except for the primary first and second molars; they are replaced by premolars.

Teething age of primary teeth:

- Central incisors: 6–12 months

- Lateral incisors: 9–16 months

- First molars: 13–19 months

- Canine teeth: 16–23 months

- Second molars: 22–33 months

Exfoliation

The replacement of primary teeth begins around age six, when the permanent teeth start to appear in the mouth, resulting in mixed dentition.[2] The upper and lower central incisors are shed at age six to seven years. The upper and lower lateral incisors are shed at seven to eight years. The upper canines are shed at ten to twelve years. The lower canines are shed at nine to twelve years. The upper and lower first molars are shed at nine to eleven years. The upper and lower second molars are shed at ten to twelve years.[3]

The erupting permanent teeth cause root resorption, where the permanent teeth push on the roots of the primary teeth, causing the roots to be dissolved by odontoclasts (as well as surrounding alveolar bone by osteoclasts) and become absorbed by the forming permanent teeth. The process of shedding primary teeth and their replacement by permanent teeth is called exfoliation. This may last from six to twelve years of age. By age twelve, there usually are only permanent teeth remaining. However, it is not extremely rare for one or more primary teeth to be retained beyond this age, sometimes well into adulthood, often because the secondary tooth fails to develop.[2]

Function

Primary teeth are essential in the development of the mouth.[4] The primary teeth maintain the arch length within the jaw, the bone and the permanent teeth replacements develop from the same tooth germs as the primary teeth. The primary teeth provide guides for the eruption pathway of the permanent teeth. Also the muscles of the jaw and the formation of the jaw bones depend on the primary teeth to maintain proper spacing for permanent teeth. The roots of primary teeth provide an opening for the permanent teeth to erupt. The primary teeth are important for the development of the child's speech, for the child's smile and play a role in chewing of food, although children who have had their primary teeth removed (usually as a result of dental caries) can still eat and chew to a certain extent.

Society and culture

In almost all European languages the primary teeth are called "baby teeth" or "milk teeth". In the United States and Canada, the term "baby teeth" is common. In some Asian countries they are referred to as "fall teeth" since they will eventually fall out.

Although shedding of a milk tooth is predominantly associated with positive emotions such as pride and joy by the majority of the children, socio-cultural factors (such as parental education, religion or country of origin) affect the various emotions children experience during the loss of their first primary tooth.[5]

Various cultures have customs relating to the loss of deciduous teeth. In English-speaking countries, the tooth fairy is a popular childhood fiction that a fairy rewards children when their baby teeth fall out. Children typically place a tooth under their pillow at night. The fairy is said to take the tooth and replace it with money or small gifts while they sleep. In some parts of Australia, Sweden and Norway, the children put the tooth in a glass of water. In medieval Scandinavia there was a similar tradition, surviving to the present day in Iceland, of tannfé ('tooth-money'), a gift to a child when it cuts its first tooth.[6][7] In Nigeria, the Igbo in a similar custom expects a visiting relative or guest to make a gift or donation to an infant upon the visitor's sighting of the infant's deciduous teeth. Hausa culture has it that a child with a fallen tooth should not let a lizard see his or her toothless gum because if a lizard does see it, no tooth will grow in its place.

Other traditions are associated with mice or other rodents because of their sharp, everlasting teeth. The character Ratón Pérez appears in the tale of The Vain Little Mouse. A Ratoncito Pérez was used by Colgate in marketing toothpaste in Venezuela[8] and Spain.[9] In Italy, the Tooth Fairy (Fatina) is also often replaced by a small mouse (topino). In France and in French-speaking Belgium, this character is called la petite souris ("The Little Mouse"). From parts of lowland Scotland comes a tradition similar to the fairy mouse: a white fairy rat who purchases the teeth with coins.

Several traditions concern throwing the shed teeth. In Turkey, Cyprus, and Greece, children traditionally throw their fallen baby teeth onto the roof of their house while making a wish. Similarly, in some Asian countries, such as India, Korea, Nepal, the Philippines, and Vietnam, when a child loses a tooth, the usual custom is that he or she should throw it onto the roof if it came from the lower jaw, or into the space beneath the floor if it came from the upper jaw. While doing this, the child shouts a request for the tooth to be replaced with the tooth of a mouse. This tradition is based on the fact that the teeth of mice grow for their entire lives, a characteristic of all rodents.

In Japan, a different variation calls for lost upper teeth to be thrown straight down to the ground and lower teeth straight up into the air or onto the roof of a house; the idea is that incoming teeth will grow in straight.[10] Some parts of China follow a similar tradition by throwing the teeth from the lower jaw onto the roof and burying the teeth from the upper jaw underground, as a symbol of urging the permanent teeth to grow faster towards the right direction.

The Sri Lankan tradition is to throw the baby teeth onto the roof or a tree in the presence of a squirrel (Funambulus palmarum). The child then tells the squirrel to take the old tooth in return for a new one.

In some parts of India, young children offer their discarded baby teeth to the sun, sometimes wrapped in a tiny rag of cotton turf. In the Assam state of India, children throw their baby teeth to the roof of their house and urge a mouse to take it, to exchange with its teeth (permanent ones).

The tradition of throwing a baby tooth up into the sky to the sun or to Allah and asking for a better tooth to replace it is common in Middle Eastern countries (including Iraq, Jordan, Egypt and Sudan). It may originate in a pre-Islamic offering and certainly dates back to at least the 13th century, when Izz bin Hibat Allah Al Hadid mentions it.[11]

In premodern Britain, lost teeth were commonly burnt to destroy them. This was partly for religious reasons connected with the Last Judgement and partly for fear of what might happen if an animal got them. A rhyme might be said as a blessing:[12]

Old tooth, new tooth

Pray God send me a new tooth

See also

- Permanent teeth

- Human tooth development

- Tooth eruption

- Tooth fairy

References

- Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Bath-Balogh and Fehrenbach, Elsevier, 2011, page 255

- Robinson, S.; Chan, M. F. W.-Y. (2009). "New teeth from old: treatment options for retained primary teeth". British Dental Journal. 207 (7): 315–20. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.855. PMID 19816477.

- "Tooth Eruption: The primary teeth". Mouth healthy.org. American Dental Association. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- "Primary teeth" (PDF). American Dental Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-08.

- Patcas, Raphael (2019). "Emotions experienced during the shedding of the first primary tooth". International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry. 29 (1): 22–28. doi:10.1111/ipd.12427. PMID 30218480.

- Cleasby, Richard; Vigfússon, Gudbrand (1957). An Icelandic-English Dictionary. William A. Craigie (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- s.v. tannfé first edition available: "An Icelandic-English Dictionary". University of Pennsylvania School of Arts and Sciences.

- ¡Producto Registrado!: Agosto 1998: Centuria Dental Archived October 20, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- Canyelles, Anna; Calafell, Roser (2012). El ratoncito Pérez (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Barcelona: La Galera. ISBN 9788424637941. OCLC 920276571.

- "Dental Practitioner". 1883.

- Al Hamdani, Muwaffak and Wenzel, Marian. "The Worm in the Tooth", Folklore, 1966, vol. 77, pp. 60-64.

- Steve Roud (2006), "Teeth: disposal of", The Penguin Guide to the Superstitions of Britain and Ireland, ISBN 978-0-14-194162-2

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Deciduous teeth. |