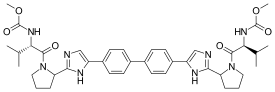

Daclatasvir

Daclatasvir, sold under the trade name Daklinza, is a medication used in combination with other medications to treat hepatitis C (HCV).[1] The other medications used in combination include sofosbuvir, ribavirin, and interferon, vary depending on the virus type and whether the person has cirrhosis.[3] It is taken by mouth once a day.[1]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /dəˈklætəsvɪər/ də-KLAT-əs-veer |

| Trade names | Daklinza[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a615044 |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth (tablets) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 67%[2] |

| Protein binding | 99%[2] |

| Metabolism | CYP3A |

| Elimination half-life | 12–15 hours |

| Excretion | Fecal (53% as unchanged drug), kidney |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C40H50N8O6 |

| Molar mass | 738.89 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Common side effects with sofusbivir and daclatasvir include headache, feeling tired, and nausea.[2] With daclatasvir, sofusbivir, and ribavirin the most common side effects are headache, feeling tired, nausea, and red blood cell breakdown.[2] It should not be used with St. John's wort, rifampin, or carbamazepine.[1] It works by inhibiting the HCV protein NS5A.[3]

Daclatasvir was approved for use in Europe in 2014 and the United States and India in 2015.[4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[5] As of January 2016 a twelve-week course cost around $63,000 in the United States, $39,000 in the United Kingdom, $37,000 in France, and $525 in Egypt.[6]

Medical use

Daclatasvir is used only in combination therapy for the treatment of hepatitis C genotype 1, 3, or 4 infections; the agents used in combination, which include sofosbuvir, ribavirin, and interferon, vary based on the virus genotype and whether the person has cirrhosis.[2][3][7][8]

It is not known whether daclatasvir passes into breastmilk or has any effect on infants.[2]

Adverse effects

There is a serious risk of bradycardia when daclatasvir is used with sofosbuvir and amiodarone[2]

Because it has not been extensively studied as a single agent, it is unknown what specific side effects are linked to this medication alone. Adverse events on daclatasvir have only been reported on combination therapy with sofusbivir or triple therapy with sofusbivir/ribavirin.[2]

Common adverse events occurring in >5% of people on combination therapy (sofusbivir + daclatasvir) include headache and fatigue; in triple therapy (daclatasvir + sofusbivir + ribavirin) the most common adverse events (>10%) include headache, fatigue, nausea and hemolytic anemia.[2]

Interactions

Concomitant use of drugs that are strong inducers of the cytochrome P450 CYP3A is contraindicated due to decreased therapeutic effect and resistance of drug.[2] Some common drugs that are strong CYP3A inducers include dexamethasone, phenytoin, carbamazepine, rifampin and St. John's Wort.[2]

Daclatasvir is a CYP3A and p-glycoprotein substrate, therefore, drugs that are strong inducers or inhibitors of these enzyme will interfere with daclatasvir levels in the body.[2] Dose modifications are made with concomitant use of daclatasvir and drugs that affect CYP3A or p-gp. When taking daclatasvir with non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, the dose of daclatasvir is increased to overcome CYP3A induction. The dose for daclatasvir should be lowered when taking with antifungals, such as ketoconazole. Currently, there are no required dosage adjustments with concurrent use of daclatasvir and immunosuppressants, narcotic analgesics, antidepressants, sedatives, and cardiovascular agents.[9]

Concurrent use with amiodarone, sofosbuvir and daclatasvir has may result in an increased risk for serious slowing of the heart rate.[2]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Daclatasvir stops HCV viral RNA replication and protein translation by directly inhibiting HCV protein NS5A.[10][11] NS5A is critical for HCV viral transcription and translation, and as of 2014 it appeared that resistance can arise to daclatasvir fairly swiftly.[10]

Pharmacokinetics

Daclatasvir reaches steady state in human subjects after about 4 days of once-daily 60 mg oral administration, with a peak dose in concentration occurring about 2 hours after administration.[2] It comes in the form of an oral tablet, with a bioavailability of 67%.[2] Daclatasvir is predominantly metabolized by the liver enzyme CYP3A4, and is also a P-gp substrate.[2] It is highly protein bound. Protein binding was measured to be around 99% in people dosed multiple times with daclatasvir independent of dose strength.[2] Daclatasvir has a volume of distribution of 47L following an oral dose of 60 mg and an IV dose of 100 μg.[2]

History

Daklinza was discovered by scientists at Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS); the precursor was identified using phenotypic screening in which the GT-1b replicon system was implemented in Huh7 cells and bovine viral diarrhea virus also in Huh7 cells was used as a counterscreen for specificity.[12] BMS also developed the drug, with the first Phase I trial publishing in 2010.[12]

It was approved for use in Europe in August 2014, in the US in July 2015, and in India in December 2015; it was first in the class of NS5A inhibitors to reach the market.[4]

Society and culture

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, a list of the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[13]

In December 2014 BMS announced that it would offer the drug for sale at different prices in different countries, depending on the level of economic development, and that it would license the drug to generics manufacturers for sale in the developing world.[14][15]

As of January 2016 a twelve-week course cost around $63,000 in the US, around $39,000 in the UK, around $37,000 in France, and $525 in Egypt, and by that time BMS had joined the Medicines Patent Pool.[6]

Research

Daclatasvir has been tested in combination regimens with pegylated interferon and ribavirin,[16] as well as with other direct-acting antiviral agents including asunaprevir and sofosbuvir.[17]

References

- "Daclatasvir Dihydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- "Daclatasvir label" (PDF). FDA. April 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-11-09.

- "Daklinza film-coated tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". Electronic Medicines Compendium. September 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-11-09.

- "Hepatitis C Treatment Snapshots: Daclatasvir" (PDF). amFAR TreatAsia. February 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-09-03.

- "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Hill, A; Simmons, B; Gotham, D; Fortunak, J (January 1, 2016). "Rapid reductions in prices for generic sofosbuvir and daclatasvir to treat hepatitis C." J Virus Erad. 2 (1): 28–31. PMC 4946692. PMID 27482432.

- Alavian, Seyed Moayed; et al. (13 August 2016). "Recommendations for the Clinical Management of Hepatitis C in Iran: A Consensus-Based National Guideline". Hepatitis Monthly. 16 (8). doi:10.5812/hepatmon.guideline. PMC 5075356. PMID 27799966.

- Pol, Stanislas; Vallet-Pichard, Anaïs; Corouge, Marion (March 2016). "Daclatasvir–sofosbuvir combination therapy with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus infection: from the clinical trials to real life". Hepatic Medicine: Evidence and Research. 8: 21–6. doi:10.2147/HMER.S62014. PMC 4786064. PMID 27019602.

- Garimella, Tushar; You, Xiaoli; Wang, Reena; Huang, Shu-Pang; Kandoussi, Hamza; Bifano, Marc; Bertz, Richard; Eley, Timothy (2016-11-01). "A Review of Daclatasvir Drug-Drug Interactions". Advances in Therapy. 33 (11): 1867–1884. doi:10.1007/s12325-016-0407-5. ISSN 1865-8652. PMC 5083780. PMID 27664109.

- Lim, Precious J; Gallay, Philippe A (October 2014). "Hepatitis C NS5A protein: two drug targets within the same protein with different mechanisms of resistance". Current Opinion in Virology. 8: 30–37. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2014.04.012. PMC 4195798. PMID 24879295.

- Bell, Thomas W. (2010). "Drugs for hepatitis C: unlocking a new mechanism of action". ChemMedChem. 5 (10): 1663–1665. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201000334. PMID 20821796.

- Belema, Makonen; Meanwell, Nicholas A. (26 June 2014). "Discovery of Daclatasvir, a Pan-Genotypic Hepatitis C Virus NS5A Replication Complex Inhibitor with Potent Clinical Effect". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 57 (12): 5057–5071. doi:10.1021/jm500335h. PMID 24749835.

- "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-05-13.

- Edwards, Danny J; Coppens, Delphi GM; Prasad, Tara L; Rook, Laurien A; Iyer, Jayasree K (1 November 2015). "Access to hepatitis C medicines". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 93 (11): 799–805. doi:10.2471/BLT.15.157784. PMC 4622162. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016.

- "MSF Briefing Document May 2015" (PDF). Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-01-18.

- Peng, Qin; Li, Kang; Cao, Ming Rong; Bie, Cai Qun; Tang, Hui Jun; Tang, Shao Hui (15 September 2016). "Daclatasvir combined with peginterferon-α and ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a meta-analysis". SpringerPlus. 5 (1). doi:10.1186/s40064-016-3218-x. PMC 5023653. PMID 27652142.

- Sulkowski, Mark S.; et al. (16 January 2014). "Daclatasvir plus Sofosbuvir for Previously Treated or Untreated Chronic HCV Infection". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (3): 211–221. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1306218. PMID 24428467.