Cytomegalovirus

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) (from the Greek cyto-, "cell," and megalo-, "large") is a genus of viruses in the order Herpesvirales, in the family Herpesviridae, in the subfamily Betaherpesvirinae. Humans and monkeys serve as natural hosts. The eight species in this genus include the type species, Human betaherpesvirus 5 (HCMV, human cytomegalovirus, HHV-5), which is the species that infects humans. Diseases associated with HHV-5 include mononucleosis, and pneumonia.[3][4] In the medical literature, most mentions of CMV without further specification refer implicitly to human CMV. Human CMV is the most studied of all cytomegaloviruses.[5]

| Cytomegalovirus | |

|---|---|

| |

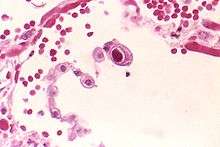

| Typical "owl eye" inclusion indicating CMV infection of a lung pneumocyte[1] | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Phylum: | incertae sedis |

| Class: | incertae sedis |

| Order: | Herpesvirales |

| Family: | Herpesviridae |

| Subfamily: | Betaherpesvirinae |

| Genus: | Cytomegalovirus |

| Type species | |

| Human betaherpesvirus 5 | |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Taxonomy

Within the Herpesviridae, CMV belongs to the Betaherpesvirinae subfamily, which also includes the genera Muromegalovirus and Roseolovirus (HHV-6 and HHV-7).[6] It is related to other herpesviruses within the subfamilies of theAlphaherpesvirinae that includes herpes simplex viruses (HSV)-1 and -2 and varicella-zoster virus, and the Gammaherpesvirinae subfamily that includes Epstein–Barr virus.[5]

Several species of Cytomegalovirus have been identified and classified for different mammals.[6] The most studied is human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), which is also known as human betaherpesvirus 5 (HHV-5). Other primate CMV species include chimpanzee cytomegalovirus (CCMV) that infects chimpanzees and orangutans, and simian cytomegalovirus (SCCMV) and Rhesus cytomegalovirus (RhCMV) that infect macaques; CCMV is known as both panine beta herpesvirus 2 (PaHV-2) and pongine betaherpesvirus 4 (PoHV-4).[7] SCCMV is called cercopithecine betaherpesvirus 5 (CeHV-5)[8] and RhCMV, Cercopithecine betaherpesvirus 8 (CeHV-8).[9] A further two viruses found in the night monkey are tentatively placed in the genus Cytomegalovirus, and are called herpesvirus aotus 1 and herpesvirus aotus 3. Rodents also have viruses previously called cytomegaloviruses that are now reclassified under the genus Muromegalovirus; this genus contains mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) is also known as murid betaherpesvirus 1 (MuHV-1) and the closely related Murid betaherpesvirus 2 (MuHV-2) that is found in rats.[10]

Species

The genus consists of these 11 species:[4]

Structure

Viruses in Cytomegalovirus are enveloped, with icosahedral, spherical to pleomorphic, and round geometries, and T=16 symmetry. The diameter is around 150–200 nm. Genomes are linear and nonsegmented, around 200 kb in length.[3]

| Genus | Structure | Symmetry | Capsid | Genomic arrangement | Genomic segmentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytomegalovirus | Spherical pleomorphic | T=16 | Enveloped | Linear | Monopartite |

Lifecycle

Viral replication is nuclear and lysogenic. Entry into the host cell is achieved by attachment of the viral glycoproteins to host receptors, which mediates endocytosis. Replication follows the dsDNA bidirectional replication model. DNA templated transcription, with some alternative splicing mechanism is the method of transcription. Translation takes place by leaky scanning. The virus exits the host cell by nuclear egress, and budding. Humans and monkeys serve as the natural hosts. Transmission routes are contact, urine, and saliva.[3]

| Genus | Host details | Tissue tropism | Entry details | Release details | Replication site | Assembly site | Transmission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytomegalovirus | Humans; monkeys | Epithelial mucosa | Glycoproteins | Budding | Nucleus | Nucleus | Urine; saliva |

All herpesviruses share a characteristic ability to remain latent within the body over long periods. Although they may be found throughout the body, CMV infections are frequently associated with the salivary glands in humans and other mammals.[6]

Genetic engineering

The CMV promoter is commonly included in vectors used in genetic engineering work conducted in mammalian cells, as it is a strong promoter and drives constitutive expression of genes under its control.[11]

History

Cytomegalovirus was first observed by German pathologist Hugo Ribbert in 1881 when he noticed enlarged cells with enlarged nuclei present in the cells of an infant.[12] Years later, between 1956 and 1957, Thomas Huckle Weller together with Smith and Rowe independently isolated the virus, known thereafter as “cytomegalovirus”.[13] In 1990, the first draft of human cytomegalovirus genome was published[14], the biggest contiguous genome sequenced at that time.[15]

See also

References

- Mattes FM, McLaughlin JE, Emery VC, Clark DA, Griffiths PD (August 2000). "Histopathological detection of owl's eye inclusions is still specific for cytomegalovirus in the era of human herpesviruses 6 and 7". J. Clin. Pathol. 53 (8): 612–4. doi:10.1136/jcp.53.8.612. PMC 1762915. PMID 11002765.

- Francki, R. I. B., Fauquet, C. M., Knudson, D. L. & Brown, F. (eds)(1991). Classification and nomenclature of viruses. Fifthreport of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Archives of Virology Supplementum 2, p.107 https://talk.ictvonline.org/ictv/proposals/ICTV%205th%20Report.pdf

- "Viral Zone". ExPASy. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ICTV. "Virus Taxonomy: 2014 Release". Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 556, 566–9. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- Koichi Yamanishi; Arvin, Ann M; Gabriella Campadelli-Fiume; Edward Mocarski; Moore, Patrick; Roizman, Bernard; Whitley, Richard (2007). Human herpesviruses: biology, therapy, and immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82714-0.

- "Panine betaherpesvirus 2 (Chimpanzee cytomegalovirus)". www.uniprot.org. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- "Simian cytomegalovirus (strain Colburn)". www.uniprot.org. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- "Macacine betaherpesvirus 3 (Rhesus cytomegalovirus)". www.uniprot.org. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- "Murid herpesvirus 1, complete genome". 13 August 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2019 – via NCBI Nucleotide. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kendall Morgan for Addgene Blog. Apr 3, 2014 Plasmids 101: The Promoter Region – Let's Go!

- Reddehase, Matthias J.; Lemmermann, Niels, eds. (2006). "Preface". Cytomegaloviruses: Molecular Biology and Immunology. Horizon Scientific Press. pp. xxiv. ISBN 9781904455028.

- Weller, T. H.; MacAuley, J. C.; Craig, J. M.; Wirth, P. (1 January 1957). "Isolation of Intranuclear Inclusion Producing Agents from Infants with Illnesses Resembling Cytomegalic Inclusion Disease". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 94 (1): 4–12. doi:10.3181/00379727-94-22841. PMID 13400856.

- Chee, M. S.; Bankier, A. T.; Beck, S.; Bohni, R.; Brown, C. M.; Cerny, R.; Horsnell, T.; Hutchison, C. A.; Kouzarides, T.; Martignetti, J. A.; Preddie, E.; Satchwell, S. C.; Tomlinson, P.; Weston, K. M.; Barrell, B. G. (1990). "Analysis of the Protein-Coding Content of the Sequence of Human Cytomegalovirus Strain AD169". Cytomegaloviruses. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 154: 125–169. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-74980-3_6. ISBN 978-3-642-74982-7. PMID 2161319.

- Martí-Carreras, Joan; Maes, Piet (2 January 2019). "Human cytomegalovirus genomics and transcriptomics through the lens of next-generation sequencing: revision and future challenges". Virus Genes. 55 (2): 138–164. doi:10.1007/s11262-018-1627-3. PMC 6458973. PMID 30604286.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cytomegalovirus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Cytomegalovirus |

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |