Creativity and mental health

The concept of a link between creativity and mental illness has been extensively discussed and studied by psychologists and other researchers for centuries. Parallels can be drawn to connect creativity to major mental disorders including bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, and ADHD. For example, studies[3] have demonstrated correlations between creative occupations and people living with mental illness. There are cases that support the idea that mental illness can aid in creativity, but it is also generally agreed that mental illness does not have to be present for creativity to exist.

History

It has been proposed that there is a particular link between creativity and mental illness (e.g. bipolar disorder, whereas major depressive disorder appears to be significantly more common among playwrights, novelists, biographers, and artists).[4] Association between mental illness and creativity first appeared in literature in the 1970s, but the idea of a link between "madness" and "genius" is much older, dating back at least to the time of Aristotle. In order to comprehend how the connection between “madness” and “genius” correlate, it is important to first understand that there are different types of geniuses: literary geniuses, creative geniuses, scholarly geniuses, and “all around” geniuses. Since there are many different categories, this means that individuals can completely excel in one subject and know an average, or below average, amount of information about others.[5] The Ancient Greeks believed that creativity came from the gods, in particular the Muses (the mythical personifications of the arts and sciences, the nine daughters of Zeus). In the Aristotelian tradition, conversely, genius was viewed from a physiological standpoint, and it was believed that the same human quality was perhaps responsible for both extraordinary achievement and melancholy.[6] Romantic writers had similar ideals, with Lord Byron having pleasantly expressed, "We of the craft are all crazy. Some are affected by gaiety, others by melancholy, but all are more or less touched".

Individuals with mental illness are said to display a capacity to see the world in a novel and original way; literally, to see things that others cannot.[7]

Studies

For many years, the creative arts have been used in therapy for those recovering from mental illness or addiction.[8][9]

Another study found creativity to be greater in schizotypal than in either normal or schizophrenic individuals. While divergent thinking was associated with bilateral activation of the prefrontal cortex, schizotypal individuals were found to have much greater activation of their right prefrontal cortex.[10] This study hypothesized that such individuals are better at accessing both hemispheres, allowing them to make novel associations at a faster rate. In agreement with this hypothesis, ambidexterity is also associated with schizotypal and schizophrenic individuals.

Three recent studies by Mark Batey and Adrian Furnham have demonstrated the relationships between schizotypal[11][12] and hypomanic personality[13] and several different measures of creativity.

Particularly strong links have been identified between creativity and mood disorders, particularly manic-depressive disorder (a.k.a. bipolar disorder) and depressive disorder (a.k.a. unipolar disorder). In Touched with Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament, Kay Redfield Jamison summarizes studies of mood-disorder rates in writers, poets and artists. She also explores research that identifies mood disorders in such famous writers and artists as Ernest Hemingway (who shot himself after electroconvulsive treatment), Virginia Woolf (who drowned herself when she felt a depressive episode coming on), composer Robert Schumann (who died in a mental institution), and even the famed visual artist Michelangelo.

A study looking at 300,000 persons with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or unipolar depression, and their relatives, found overrepresentation in creative professions for those with bipolar disorder as well as for undiagnosed siblings of those with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. There was no overall overrepresentation, but overrepresentation for artistic occupations, among those diagnosed with schizophrenia. There was no association for those with unipolar depression or their relatives.[14]

A study involving more than one million people, conducted by Swedish researchers at the Karolinska Institute, reported a number of correlations between creative occupations and mental illnesses. Writers had a higher risk of anxiety and bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, unipolar depression, and substance abuse, and were almost twice as likely as the general population to kill themselves. Dancers and photographers were also more likely to have bipolar disorder.[15]

However, as a group, those in the creative professions were no more likely to experience psychiatric disorders than other people, although they were more likely to have a close relative with a disorder, including anorexia and, to some extent, autism, the Journal of Psychiatric Research reports.[16]

Research in this area is usually constrained to cross-section data-sets. One of the few exceptions is an economic study of the well-being and creative output of three famous music composers over their entire lifetime.[17] The emotional indicators are obtained from letters written by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Liszt, and the results indicate that negative emotions had a causal impact on the creative production of the artists studied.

Psychological stress has also been found to impede spontaneous creativity.[18][19]

A 2005 study at the Stanford University School of Medicine measured creativity by showing children figures of varying complexity and symmetry and asking whether they like or dislike them. The study showed for the first time that a sample of children who either have or are at high risk for bipolar disorder tend to dislike simple or symmetric symbols more. Children with bipolar parents who were not bipolar themselves also scored higher dislike scores.[20]

Mood and creativity

Mood-creativity research reveals that people are most creative when they are in a positive mood[21][22] and that mental illnesses such as depression or schizophrenia actually decrease creativity.[23][24] People who have worked in the field of arts throughout the history have had problems with poverty, persecution, social alienation, psychological trauma, substance abuse, high stress[25] and other such environmental factors which are associated with developing and perhaps causing mental illness. It is thus likely that when creativity itself is associated with positive moods, happiness, and mental health, pursuing a career in the arts may bring problems with stressful environment and income. Other factors such as the centuries-old stereotype of the suffering of a "mad artist" help to fuel the link by putting expectations on how an artist should act, or possibly making the field more attractive to those with mental illness. Additionally, where specific areas of the brain are less developed than others by nature or external influence, the spacial capacity to expand another increases beyond "the norm" allowing enhanced growth and development.

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is one of the main mental disorders said to inspire creativity, as the manic episodes are typically characterised by prolonged and elevated periods of energy. In her book Touched with Fire, American clinical psychologist Kay Redfield Jamison wrote that 38% of writers and poets had been treated for a type of mood disorder, and virtually all creative writers and artists (89%) had experienced "intense, highly productive, and creative episodes". These were characterised by "pronounced increases in enthusiasm, energy, self-confidence, speed of mental association, fluency of thought and elevated mood".[26] There is a range of types of bipolar disorder. Individuals with Bipolar I Disorder experience severe episodes of mania and depression with periods of wellness between episodes. The severity of the manic episodes can mean that the person is seriously disabled and unable to express the heightened perceptions and flight of thoughts and ideas in a practical way. Individuals with Bipolar II Disorder experience milder periods of hypomania during which the flight of ideas, faster thought processes and ability to take in more information can be converted to art, poetry or design.[27] Dutch artist Vincent Van Gogh is widely theorised to have suffered from bipolar disorder. Other notable creative people with bipolar disorder include Carrie Fisher, Demi Lovato, Kanye West, Stephen Fry (who suffers from cyclothymia, a milder and more chronic form of bipolar),[28] Mariah Carey, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Jean-Claude Van Damme, Ronald Braunstein[29][30] , and Patty Duke[31]

Schizophrenia

People with schizophrenia live with positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms. Positive symptoms (psychotic behaviors that are not present in healthy people) include hallucinations, delusions, and thought and movement disorders. Negative symptoms (abnormal functioning of emotions and behavior) include "flat affect", anhedonia, reserved. Cognitive symptoms include problems with "executive functioning", attention, and memory.[32] One artist known for his schizophrenia was the Frenchman Antonin Artaud, founder of the Theatre of Cruelty movement. In Madness and Modernism (1992), clinical psychologist Louis A. Sass noted that many common traits of schizophrenia – especially fragmentation, defiance of authority, and multiple viewpoints – happen to also be defining features of modern art.[33]

Arguments that support link

In a 2002 conversation with Christopher Langan, educational psychologist Arthur Jensen stated that the relationship between creativity and mental disorder "has been well researched and is proven to be a fact", writing that schizothymic characteristics are somewhat more frequent in philosophers, mathematicians, and scientists than in the general population.[34] In a 2015 study, Iceland scientists found that people in creative professions are 25% more likely to have gene variants that increase the risk of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, with deCODE Genetics co-founder Kári Stefánsson saying, "Often, when people are creating something new, they end up straddling between sanity and insanity. I think these results support the concept of the mad genius."[35]

Bipolar Disorder

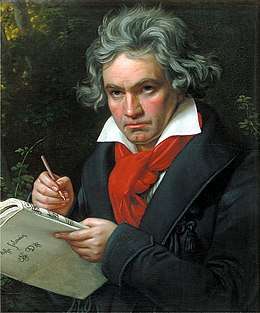

Many famous historical figures gifted with creative talents may have been affected by bipolar disorder. Ludwig van Beethoven, Virginia Woolf, Ernest Hemingway, Isaac Newton, Judy Garland and Robert Schumann are some people whose lives have been researched to discover signs of mood disorder.[36] In many instances, creativity and mania - the overwhelming highs that bipolar individuals often experience - share some common traits, such as a tendency for "thinking outside the box," flights of ideas, the speeding up of thoughts and heightened perception of visual, auditory and somatic stimuli.

It has been found that the brains of creative people are more open to environmental stimuli due to smaller amounts of latent inhibition, an individual's unconscious capacity to ignore unimportant stimuli. While the absence of this ability is associated with psychosis, it has also been found to contribute to original thinking.[37]

Emotions

Many people with bipolar disorder may feel powerful emotions during both depressive and manic phases, potentially aiding in creativity.[38] Because (hypo)mania decreases social inhibition, performers are often daring and bold. As a consequence, creators commonly exhibit characteristics often associated with mental illness. The frequency and intensity of these symptoms appear to vary according to the magnitude and domain of creative achievement. At the same time, these symptoms are not equivalent to the full-blown psychopathology of a clinical manic episode which, by definition, entails significant impairment.[39]

Posthumous diagnosis

Some creative people have been posthumously diagnosed as experiencing bipolar or unipolar disorder based on biographies, letters, correspondence, contemporaneous accounts, or other anecdotal material, most notably in Kay Redfield Jamison's book Touched with Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament.[40] Touched with Fire presents the argument that bipolar disorder, and affective disorders more generally,[41] may be found in a disproportionate number of people in creative professions such as actors, artists, comedians, musicians, authors, performers and poets.

Scholars have also speculated that the visual artist Michelangelo lived with depression. In the book Famous Depressives: Ten Historical Sketches, MJ Van Lieburg argues that elements of depression are prominent in some of Michelangelo's sculptures and poetry. Van Lieburg also draws additional support from Michelangelo's letters to his father in which he states:

"I lead a miserable existence and reck not of life nor honour - that is of this world; I live wearied by stupendous labours and beset by a thousand anxieties. And thus I lived for some fifteen years now and never an hour's happiness have I had." [42]

Positive correlation

Several recent clinical studies have also suggested that there is a positive correlation between creativity and bipolar disorder, although the relationship between the two is unclear.[43][44][45] Temperament may be an intervening variable.[44] Ambition has also been identified as being linked to creative output in people across the bipolar spectrum.[46]

Mental illness and divergent thinking

In 2017, associate professor of psychiatry Gail Saltz stated that the increased production of divergent thoughts in people with mild-to-moderate mental illnesses leads to greater creative capacities. Saltz argued that the "wavering attention and day-dreamy state" of ADHD, for example, "is also a source of highly original thinking. [...] CEOs of companies such as Ikea and Jetblue have ADHD. Their creativity, out-of-the-box thinking, high energy levels, and disinhibited manner could all be a positive result of their negative affliction."[47] Mania has also been credited with aiding in creativity because "when speed of thinking increases, word associations form more freely, as do flight of ideas, because the manic mind is less inclined to filtering details that, in a normal state, would be dismissed as irrelevant."[33]

Arguments against a link

Albert Rothenberg of Psychology Today noted that the "list of mentally ill creators who were successful [...] is dwarfed by the very large number of highly creative people both in modern times and throughout history without evidence of disorder", which includes figures such as William Shakespeare, Johann Sebastian Bach, and Jane Austen.[48] Rothenberg reported that when interviewing 45 science Nobel laureates for the book Flight from Wonder he had found no evidence of mental illness in any of them, and also stated, "The problem is that the criteria for being creative is never anything very creative. Belonging to an artistic society, or working in art or literature, does not prove a person is creative. But the fact is that many people who have mental illness do try to work in jobs that have to do with art and literature, not because they are good at it, but because they're attracted to it. And that can skew the data."[49]

Notable individuals

- Joanne Greenberg's novel I Never Promised You a Rose Garden (1964) is an autobiographical account of her teenage years in Chestnut Lodge working with Dr. Frieda Fromm-Reichmann. At the time she was diagnosed with schizophrenia, although two psychiatrists who examined Greenberg's self-description in the book in 1981 concluded that she did not have schizophrenia, but had extreme depression and somatization disorder.[50] The narrative constantly puts difference between the protagonist's mental illness and her artistic ability. Greenberg is adamant that her creative skills flourished in spite of, not because of, her condition.[51]

- Brian Wilson (born 1942), founder of the American rock band the Beach Boys, suffers from schizoaffective disorder. In 2002, after undergoing treatment, he spoke of how medication affects his creativity, explaining: "I haven't been able to write anything for three years. I think I need the demons in order to write, but the demons have gone. It bothers me a lot. I've tried and tried, but I just can't seem to find a melody."[52]

- Daniel Johnston (1961-2019) was an outsider musician sometimes celebrated as "the Brian Wilson of lo-fi". His music is often attributed to his psychological issues. In a press release issued by his manager, it was requested that reporters refrain from describing Johnston as a "genius" due to the musician's emotional instabilities. The Guardian's David McNamee argued that "it's almost taboo to say anything critical about Johnston. This is incredibly patronising. For one thing, it makes any honest evaluation of his work impossible."[53]

- Terry A. Davis (1969–2018) was a computer programmer who created and designed an entire operating system, TempleOS, by himself. Although his remarks were often incomprehensible or abrasive, he was known to be exceptionally lucid if the topic of discussion was computers. He refused medication for his schizophrenia because he believed it limited his creativity.[54] In 2017, the OS was shown as a part of an outsider art exhibition in Bourogne, France.[55]

See also

- Savant syndrome

- Outsider art § Art of the mentally ill

References

- Martin Mai, François (2007). Diagnosing Genius: The Life and Death of Beethoven. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 978-0773578791.

There is a strong possibility that he had recurrent depressive episodes, and it is also likely that he had what would now be called a bipolar disorder.

- Goodnick, Paul J. (1998). Mania: Clinical and Research Perspectives. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 15. ISBN 978-0880487283.

- Kyaga, Simon; Landén, Mikael; Boman, Marcus; Hultman, Christina M.; Långström, Niklas; Lichtenstein, Paul (January 2013). "Mental illness, suicide and creativity: 40-year prospective total population study". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 47 (1): 83–90. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.09.010. ISSN 1879-1379. PMID 23063328.

- Goodwin, F. and Jamison, K. R., Manic Depressive Illness, Oxford University Press (Oxford, 1990), p. 353.

- Kaufman, James C. "Two." Creativity and Mental Illness. United Kingdom: Cambridge U House, 2014. 31–38. Print.

- Romeo, Nick (November 9, 2013). "What is a Genius?". The Daily Beast. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- Andreasen, N.C. (2011), "A journey into chaos: Creativity and the unconscious", Mens Sana Monographs, 9:1, p 42–53. Retrieved 2011-03-27

- Malchiodi, Cathy (June 30, 2014). "Creative Arts Therapy and Expressive Arts Therapy". Psychology Today. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- Heenan, Deirdre (March 2006). "Art as therapy: an effective way of promoting positive mental health?". Disability & Society. 21 (2): 179–191. doi:10.1080/09687590500498143.

- Folley, Bradley S.; Park, Sohee (December 2005). "Verbal creativity and schizotypal personality in relation to prefrontal hemispheric laterality: A behavioral and near-infrared optical imaging study". Schizophrenia Research. 80 (2–3): 271–282. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2005.06.016. PMC 2817946. PMID 16125369.

- Batey M. Furnham (2009). "The relationship between creativity, schizotypy and intelligence". Individual Differences Research. 7: 272–284.

- Batey M., Furnham A. (2008). "The relationship between measures of creativity and schizotypy". Personality and Individual Differences. 45 (8): 816–821. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.08.014.

- Furnham A., Batey M., Anand K., Manfield J. (2008). "Personality, hypomania, intelligence and creativity". Personality and Individual Differences. 44 (5): 1060–1069. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.10.035.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kyaga, S.; Lichtenstein, P.; Boman, M.; Hultman, C.; Långström, N.; Landén, M. (2011). "Creativity and mental disorder: Family study of 300 000 people with severe mental disorder". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 199 (5): 373–379. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085316. PMID 21653945.

- Kyaga, Simon; Landén, Mikael; Boman, Marcus; Hultman, Christina M.; Långström, Niklas; Lichtenstein, Paul (January 2013). "Mental illness, suicide and creativity: 40-Year prospective total population study". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 47 (1): 83–90. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.09.010. PMID 23063328.

- Kyaga, Simon; Landén, Mikael; Boman, Marcus; Hultman, Christina M.; Långström, Niklas; Lichtenstein, Paul (January 2013). "Mental illness, suicide and creativity: 40-Year prospective total population study". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 47 (1): 83–90. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.09.010. PMID 23063328.

- Borowiecki, Karol Jan (October 2017). "How Are You, My Dearest Mozart? Well-Being and Creativity of Three Famous Composers Based on Their Letters" (PDF). The Review of Economics and Statistics. 99 (4): 591–605. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00616.

- The science of creativity

- Byron, Kristin; Khazanchi, Shalini; Nazarian, Deborah (2010). "The relationship between stressors and creativity: A meta-analysis examining competing theoretical models". Journal of Applied Psychology. 95 (1): 201–212. doi:10.1037/a0017868. PMID 20085417.

- Children Of Bipolar Parents Score Higher On Creativity Test, Stanford Study Finds

- Mark A. Davis (January 2009). "Understanding the relationship between mood and creativity: A meta-analysis". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 100 (1): 25–38. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.04.001.

- Baas, Matthijs; De Dreu Carsten K. W. & Nijstad, Bernard A. (November 2008). "A meta-analysis of 25 years of mood-creativity research: Hedonic tone, activation, or regulatory focus?" (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 134 (6): 779–806. doi:10.1037/a0012815. PMID 18954157. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- Takahiro Nemotoa; Ryoko Yamazawaa; Hiroyuki Kobayashia; Nobuharu Fujitaa; Bun Chinoa; Chiyo Fujiid; Haruo Kashimaa; Yuri Rassovskye; Michael F. Greenc; Masafumi Mizunof (November 2009). "Cognitive training for divergent thinking in schizophrenia: A pilot study". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 33 (8): 1533–1536. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.08.015. PMID 19733608.

- Flaherty AW (2005). "Frontotemporal and dopaminergic control of idea generation and creative drive". J Comp Neurol. 493 (1): 147–53. doi:10.1002/cne.20768. PMC 2571074. PMID 16254989.

- Arnold M. Ludwig (1995) The Price of Greatness: Resolving the Creativity and Madness Controversy ISBN 978-0-89862-839-5

- R., Jamison, Kay (1996). Touched with fire : manic-depressive illness and the artistic temperament. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0684831831. OCLC 445006821.

- Parker, G., (ed.) "Bipolar II Disorder: modeling, measuring and managing", Cambridge University Press (Cambridge,2005).

- "Cyclothymia (cyclothymic disorder) - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- "Franz Strasser and David Botti (2013-1-7). "Conductor with bipolar disorder on music and mental illness", BBC News".

- "David Gram for the Associated Press (2013-12-27). "For this orchestra, playing music is therapeutic", The Boston Globe". Archived from the original on 2019-04-14. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- "Famous people with bipolar disorder". 2018-04-11. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- "Schizophrenia". www.nimh.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- Frey, Angelica (May 3, 2017). "A New Account of Robert Lowell's Mania Risks Glorifying It". Hyperallergic. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- Discussions on Genius and Intelligence. Mega Foundation Press. 2002. Archived from the original on 2017-12-28. Retrieved 2017-07-09.

- Turner, Camilla (June 9, 2015). "Creative people are more likely to suffer from mental illness, study claims". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- Goodnick, P.J. (ed.) Mania: clinical and research perspectives. American Psychiatric Press, Washington, 1998.

- "Biological Basis For Creativity Linked To Mental Illness". Science Daily. October 1, 2003. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- Are Genius and Madness Related? Contemporary Answers to an Ancient Question | Psychiatric Times

- Dean Keith Simonton (June 2005). "Are Genius and Madness Related? Contemporary Answers to an Ancient Question". Psychiatric Times. Retrieved 2007-02-20.

- Kay Redfield Jamison (1996). Touched with Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-684-83183-1.

- Jamison, K. R., Touched with Fire, Free Press (New York, 1993), pp 82 ff.

- Van Lieburg, MJ (1988). Famous Depressives: Ten Historical Sketches. Rotterdam: Erasmus Publishin. pp. 19–26. ISBN 9789052350073.

- Santosa CM, Strong CM, Nowakowska C, Wang PW, Rennicke CM, Ketter TA (June 2007). "Enhanced creativity in bipolar disorder patients: a controlled study". J Affect Disord. 100 (1–3): 31–9. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.013. PMID 17126406.

- Rihmer Z, Gonda X, Rihmer A (2006). "[Creativity and mental illness]". Psychiatr Hung (in Hungarian). 21 (4): 288–94. PMID 17170470.

- Nowakowska C, Strong CM, Santosa CM, Wang PW, Ketter TA (March 2005). "Temperamental commonalities and differences in euthymic mood disorder patients, creative controls, and healthy controls". J Affect Disord. 85 (1–2): 207–15. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2003.11.012. PMID 15780691.

- Johnson SL, Murray G, Hou S, Staudenmaier PJ, Freeman MA, Michalak EE; CREST.BD. (2015). "Creativity is linked to ambition across the bipolar spectrum". J Affect Disord. 178 (Jun 1): 160–4. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.021. PMID 25837549.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Saltz, Dr. Gail (April 16, 2017). "To remove the stigma of mental illness, we need to accept how complex—and sometimes beautiful—it is". Quartz. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- Rothenberg, Albert (March 8, 2015). "Creativity and Mental Illness". Psychology Today. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- Sample, Ian (June 8, 2015). "New study claims to find genetic link between creativity and mental illness". The Guardian. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- Sobel, Dava (February 17, 1981). "Schizophrenia In Popular Books: A Study Finds Too Much Hope". The New York Times.

- "I wrote [I Never Promised You a Rose Garden] as a way of describing mental illness without the romanticisation [sic] that it underwent in the sixties and seventies when people were taking LSD to simulate what they thought was a liberating experience. During those days, people often confused creativity with insanity. There is no creativity in madness; madness is the opposite of creativity, although people may be creative in spite of being mentally ill." This statement from Greenberg originally appeared on the page for Rose Garden at amazon.com and has been quoted in many places including Asylum: A Mid-Century Madhouse and Its Lessons About Our Mentally Ill Today, by Enoch Callaway, M.D. (Praeger, 2007), p. 82.

- O'Hagan, Sean (2002-01-06). "Feature: A Boy's Own Story". Review, the Observer (January 6, 2002). pp. 1–3.

- McNamee, David (August 10, 2009). "The myth of Daniel Johnston's genius". The Guardian.

- Cassel, David (September 23, 2018). "The Troubled Legacy of Terry Davis, 'God's Lonely Programmer'". The New Stack.

- Godin, Philippe (January 13, 2013). "la Diagonale de l'art - ART BRUT 2.0". Libération (in French). Retrieved September 7, 2018.

External links

- The 'Sylvia Plath' effect by Deborah Smith Bailey from American Psychological Association

- The Myth of the Mentally Ill Creative blog entry about creativity and mental illness by a professor of psychology and creativity scientist Keith Sawyer

- A journey into chaos: Creativity and the unconscious by Nancy C Andreasen, Mens Sana Monographs, 2011, 9(1), p 42–53.