Cotard delusion

Cotard delusion, also known as walking corpse syndrome or Cotard's syndrome, is a rare mental disorder in which the affected person holds the delusional belief that they are already dead, do not exist, are putrefying, or have lost their blood or internal organs.[1] Statistical analysis of a hundred-patient cohort indicated that the denial of self-existence is a symptom present in 45% of the cases of Cotard's syndrome; the other 55% of the patients presented delusions of immortality.[2]

| Cotard delusion | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cotard's syndrome, walking corpse syndrome |

| |

| The neurologist Jules Cotard (1840–89) described "The Delirium of Negation" as a mental illness of varied severity. | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

In 1880, the neurologist Jules Cotard described the condition as Le délire des négations ("The Delirium of Negation"), a psychiatric syndrome of varied severity. A mild case is characterized by despair and self-loathing, while a severe case is characterized by intense delusions of negation and chronic psychiatric depression.[3][4] The case of Mademoiselle X describes a woman who denied the existence of parts of her body and of her need to eat. She said that she was condemned to eternal damnation and therefore could not die a natural death. In the course of suffering "The Delirium of Negation", Mademoiselle X died of starvation.

The Cotard delusion is not mentioned in either the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)[5] or the tenth edition of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) of the World Health Organization.[6]

Signs and symptoms

The delusion of negation is the central symptom in Cotard's syndrome. The patient afflicted with this mental illness usually denies their own existence, the existence of a certain body part, or the existence of a portion of their body. Cotard's syndrome exists in three stages: (i) Germination stage—the symptoms of psychotic depression and of hypochondria appear; (ii) Blooming stage—the full development of the syndrome and the delusions of negation; and (iii) Chronic stage—continued, severe delusions along with chronic psychiatric depression.[7]

The Cotard syndrome withdraws the afflicted person from other people due to the neglect of their personal hygiene and physical health. The delusion of negation of self prevents the patient from making sense of external reality, which then produces a distorted view of the external world. Such a delusion of negation is usually found in the psychotic patient who also presents with schizophrenia. Although a diagnosis of Cotard's syndrome does not require the patient's having had hallucinations, the strong delusions of negation are comparable to those found in schizophrenic patients.[8]

Distorted reality

The article Betwixt Life and Death: Case Studies of the Cotard Delusion (1996) describes a contemporary case of Cotard delusion, which occurred in a Scotsman whose brain was damaged in a motorcycle accident:

[The patient's] symptoms occurred in the context of more general feelings of unreality and [of] being dead. In January 1990, after his discharge from hospital in Edinburgh, his mother took him to South Africa. He was convinced that he had been taken to Hell (which was confirmed by the heat), and that he had died of sepsis (which had been a risk early in his recovery), or perhaps from AIDS (he had read a story in The Scotsman about someone with AIDS who died from sepsis), or from an overdose of a yellow fever injection. He thought he had "borrowed [his] mother's spirit to show [him] around hell", and that she was asleep in Scotland.[9]

The article Recurrent Postictal Depression with Cotard Delusion (2005) describes the case of a fourteen-year-old epileptic boy who experienced Cotard syndrome after seizures. His mental health history was of a boy expressing themes of death, chronic sadness, decreased physical activity in playtime, social withdrawal, and disturbed biological functions. About twice a year, the boy suffered episodes that lasted between three weeks and three months. In the course of each episode, he said that everyone and everything was dead (including trees), described himself as a dead body, and warned that the world would be destroyed within hours. Throughout the episode, the boy showed no response to pleasurable stimuli and had no interest in social activities.[10]

Pathophysiology

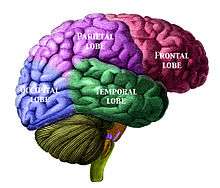

The underlying neurophysiology and psychopathology of Cotard syndrome might be related to problems of delusional misidentification. Neurologically, the Cotard delusion (negation of the Self) is thought to be related to the Capgras delusion (people replaced by impostors); each type of delusion is thought to result from neural misfiring in the fusiform face area of the brain, which recognizes faces, and in the amygdalae, which associate emotions to a recognized face.[11]

The neural disconnection creates in the patient a sense that the face they are observing is not the face of the person to whom it belongs; therefore, that face lacks the familiarity (recognition) normally associated with it. This results in derealization, or a disconnection from the environment. If the observed face is that of a person known to the patient, they experience that face as the face of an impostor (the Capgras delusion). If the patient sees their own face, they might perceive no association between the face and their own sense of Self—which results in the patient believing that they do not exist (the Cotard delusion).

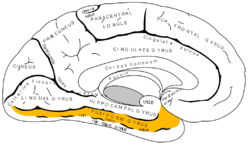

Cotard's syndrome is usually encountered in people afflicted with psychosis, as in schizophrenia,[12] neurological illness, mental illness, clinical depression, derealization, brain tumor,[13][14] and with migraine headache.[11] The medical literature indicate that the occurrence of Cotard's delusion is associated with lesions in the parietal lobe. As such, the Cotard-delusion patient presents a greater incidence of brain atrophy—especially of the median frontal lobe—than do the people in the control groups.[15]

The Cotard delusion also has resulted from a patient's adverse physiological response to a drug (e.g., aciclovir) and to its prodrug precursor (e.g., valaciclovir). The occurrence of Cotard delusion symptoms was associated with a high serum-concentration of 9-carboxymethoxymethylguanine (CMMG), the principal metabolite of the drug aciclovir. As such, the patient with weak kidneys (impaired renal function) continued risking the occurrence of delusional symptoms, despite the reduction of the dose of aciclovir. Hemodialysis resolved the patient's delusions (of negating the Self) within hours of treatment, which suggests that the occurrence of Cotard-delusion symptoms might not always be cause for psychiatric hospitalization of the patient.[16]

Diagnostic criteria

According to the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition), Cotard delusion falls under the category of somatic delusions, those that involve bodily functions or sensations.

There are no further diagnostic criteria for Cotard syndrome within the DSM-5, and identification of the syndrome relies heavily on clinical interpretation.

Cotard delusion should not be confused with delusional disorders as defined by the DSM-5, which involve a different spectrum of symptoms that are less severe and have lesser detrimental effect on functioning.

Treatment

Pharmacological treatments, both mono-therapeutic and multi-therapeutic, using antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers have been reported successful.[17] Likewise, with the depressed patient, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is more effective than pharmacotherapy.[17] Cotard syndrome resulting from an adverse drug reaction to valacyclovir is attributed to elevated serum concentration of one of valacyclovir's metabolites, 9-carboxymethoxymethylguanine (CMMG). Successful treatment warrants cessation of the drug, valacyclovir. Hemodialysis was associated with timely clearance of CMMG and resolution of symptoms.

Case studies

- One patient, referred to as WI for privacy reasons, was diagnosed with Cotard delusion after experiencing significant traumatic brain damage. Damage to the cerebral hemisphere, frontal lobe, and the ventricular system was apparent to WI's doctors after examining magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans. In January 1990, WI was discharged to outpatient care. Although his family had made arrangements for him to travel abroad, he continued to experience significant persistent visual difficulties, which provoked a referral for ophthalmological assessment. Formal visual testing then led to the discovery of further damage. For several months after the initial trauma, WI continued to experience difficulty recognizing familiar faces, places, and objects. He also was convinced that he was dead and experienced feelings of derealization. Later in 1990, after being discharged from the hospital, WI was convinced that he had been taken to hell after dying of either AIDS or sepsis. When WI finally sought out neurological testing in May 1990, he was no longer fully convinced that he was dead, although he still suspected it. Further testing revealed that WI was able to distinguish between dead and alive individuals with the exception of himself. When WI was treated for depression, his delusions of his own death diminished in a month.[18]

- In November 2016, the Daily Mirror newspaper carried a report of Warren McKinlay of Braintree in Essex, who developed Cotard's delusion following a serious motorbike accident.[19]

See also

- Depersonalization disorder

- Mortality salience

- Prosopagnosia

- Self-verification theory

- Solipsism

- Mirrored-self misidentification

References

- Berrios G.E.; Luque R. (1995). "Cotard's delusion or syndrome?". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 36 (3): 218–223. doi:10.1016/0010-440x(95)90085-a.

- Berrios G.E.; Luque R. (1995). "Cotard Syndrome: Clinical Analysis of 100 Cases". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 91 (3): 185–188. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1995.tb09764.x. PMID 7625193.

- Cotard's syndrome at Who Named It?

- Berrios G.E.; Luque R. (1999). "Cotard's 'On Hypochondriacal Delusions in a Severe form of Anxious Melancholia". History of Psychiatry. 10 (38): 269–278. doi:10.1177/0957154x9901003806. PMID 11623880.

- Debruyne H.; et al. (Jun 2009). "Cotard's syndrome: a review". Curr Psychiatry Rep. 11 (3): 197–202. doi:10.1007/s11920-009-0031-z. PMID 19470281.

- Debruyne Hans; et al. (2011). "Cotard's Syndrome". Mind & Brain. 2.

- Yarnada, K.; Katsuragi, S.; Fujii, I. (13 November 2007). "A Case Study of Cotard's syndrome: Stages and Diagnosis". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 100 (5): 396–398. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10884.x. PMID 10563458.

- Young, A.W., Robertson, I.H., Hellawell, D.J., de, P.K.W., & Pentland, B. (January 01, 1992). Cotard delusion after Brain Injury. Psychological Medicine, 22, 3, 799–804.

- Young, A.W.; Leafhead, K.M. (1996). "Betwixt Life and Death: Case Studies of the Cotard Delusion". In Halligan, P.W.; Marshall, J.C. (eds.). Method in Madness: Case studies in Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. Hove: Psychology Press. p. 155.

- Mendhekar, D. N., & Gupta, N. (January 01, 2005). "Recurrent Postictal Depression with Cotard delusion." Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 72, 6, 529–31.

- Pearn, J.; Gardner-Thorpe, C (May 14, 2002). "Jules Cotard (1840–1889) His Life and the Unique Syndrome that bears his Name". Neurology (abstract). 58 (9): 1400–3. doi:10.1212/wnl.58.9.1400. PMID 12011289.

- Morgado, Pedro; Ribeiro, Ricardo; Cerqueira, João J. (2015). "Cotard Syndrome without Depressive Symptoms in a Schizophrenic Patient". Case Reports in Psychiatry. 2015: 643191. doi:10.1155/2015/643191. ISSN 2090-682X. PMC 4458527. PMID 26101683.

- Gonçalves, Luís Moreira; Tosoni, Alberto; Gonçalves, Luís Moreira; Tosoni, Alberto (April 2016). "Sudden onset of Cotard's syndrome as a clinical sign of brain tumor" (PDF). Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo). 43 (2): 35–36. doi:10.1590/0101-60830000000080. ISSN 0101-6083.

- Bhatia, M. S. (August 1993). "Cotard's Syndrome in parietal lobe tumor". Indian Pediatrics. 30 (8): 1019–1021. ISSN 0019-6061. PMID 8125572.

- Joseph, AB; O'Leary, DH (Oct 1986). "Brain Atrophy and Interhemispheric fissure Enlargement in Cotard's syndrome". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 47 (10): 518–20. PMID 3759917.

- Anders Helldén; Ingegerd Odar-Cederlöf; Kajsa Larsson; Ingela Fehrman-Ekholm; Thomas Lindén (December 2007). "Death Delusion" (Journal Article). BMJ. 335 (7633): 1305. doi:10.1136/bmj.39408.393137.BE. PMC 2151143. PMID 18156240.

- Debruyne H.; Portzky M.; Van den Eynde F.; Audenaert K. (June 2010). "Cotard's syndrome: A Review". Current Psychiatry Reports. 11 (3): 197–202. doi:10.1007/s11920-009-0031-z. PMID 19470281.

- Halligan, P. W., & Marshall, J. C. (2013). Method in madness: Case studies in cognitive neuropsychiatry. Psychology Press.

- Soldier was 'walking corpse' after rare medical condition convinced him he was dead Daily Mirror by Martin Fricker and Sarah Arnold 30 November 2016

Young, A., Robertson, I., Hellawell, D., De Pauw, K., & Pentland, B. (1992). Cotard delusion after brain injury. Psychological Medicine, 22(3), 799-804. doi:10.1017/S003329170003823X