Coronary stent

A coronary stent is a tube-shaped device placed in the coronary arteries that supply blood to the heart, to keep the arteries open in the treatment of coronary heart disease. It is used in a procedure called percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Coronary stents are now used in more than 90% of PCI procedures.[1] Stents reduce angina (chest pain) and have been shown to improve survivability and decrease adverse events in an acute myocardial infarction.[2][3]

| Coronary stent | |

|---|---|

An example of a coronary stent. This Taxus stent is labeled as a drug-eluting stent. | |

| ICD-9-CM | 36.06 |

Similar stents and procedures are used in non-coronary vessels (e.g., in the legs in peripheral artery disease).

Medical uses

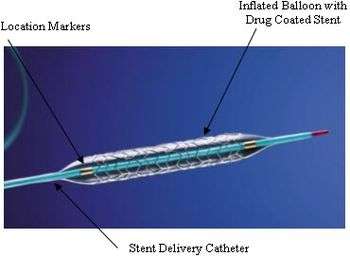

Treating a blocked ("stenosed") coronary artery with a stent follows the same steps as other angioplasty procedures with a few important differences. The interventional cardiologist uses angiography to assess the location and estimate the size of the blockage ("lesion") by injecting a contrast medium through the guide catheter and viewing the flow of blood through the downstream coronary arteries. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) may be used to assess the lesion's thickness and hardness ("calcification"). The cardiologist uses this information to decide whether to treat the lesion with a stent and if so, what kind and size. Drug-eluting stents are most often sold as a unit, with the stent in its collapsed form attached to the outside of a balloon catheter. Outside the US, physicians may perform "direct stenting", where the stent is threaded through the lesion and expanded. Common practice in the US is to predilate the blockage before delivering the stent. Predilation is accomplished by threading the lesion with an ordinary balloon catheter and expanding it to the vessel's original diameter. The physician withdraws this catheter and threads the stent on its balloon catheter through the lesion. The physician expands the balloon, which deforms the metal stent to its expanded size. The cardiologist may "customize" the fit of the stent to match the blood vessel's shape, using IVUS to guide the work.[4] It is critically important that the framework of the stent be in direct contact with the walls of the vessel to minimize potential complications such as blood clot formation. Very long lesions may require more than one stent—the result of this treatment is sometimes referred to as a "full metal jacket".[5]

The procedure itself is performed in a catheterization clinic ("cath lab"). Barring complications, patients undergoing catheterizations are kept at least overnight for observation.[6]

Dealing with lesions near branches in the coronary arteries presents additional challenges and requires additional techniques.[7]

Risks

Though the chances of having complications from a PCI are small, some serious complications include the development of arrythmias, adverse reactions/effects of the dye used in the procedure, infection, restenosis, clotting, blood vessel damage, and bleeding at catheter insertion site.[8]

Re-occlusion

Coronary artery stents, typically a metal framework, can be placed inside the artery to help keep it open. However, as the stent is a foreign object (not native to the body), it incites an immune response. This may cause scar tissue (cell proliferation) to rapidly grow over the stent. In addition, if the stent damages the artery wall there is a strong tendency for clots to form at the site. Since platelets are involved in the clotting process, patients must take dual antiplatelet therapy starting immediately before or after stenting: usually an ADP receptor antagonist (e.g. clopidogrel or ticagrelor) and aspirin for up to one year and aspirin indefinitely.[9][1]

However, in some cases the dual antiplatelet therapy may be insufficient to fully prevent clots that may result in stent thrombosis; these clots and cell proliferation may sometimes cause standard (“bare-metal”) stents to become blocked (restenosis). Drug-eluting stents were developed with the intent of dealing with this problem: by releasing an antiproliferative drug (drugs typically used against cancer or as immunosuppressants), they can help reduce the incidence of "in-stent restenosis" (re-narrowing).

Restenosis

One of the drawbacks of vascular stents is the potential for restenosis via the development of a thick smooth muscle tissue inside the lumen, the so-called neointima. Development of a neointima is variable but can at times be so severe as to re-occlude the vessel lumen (restenosis), especially in the case of smaller-diameter vessels, which often results in reintervention. Consequently, current research focuses on the reduction of neointima after stent placement. Substantial improvements have been made, including the use of more biocompatible materials, anti-inflammatory drug-eluting stents, resorbable stents, and others. Restenosis can be treated with a reintervention using the same method.

Controversy

The value of stenting in rescuing someone having a heart attack (by immediately alleviating an obstruction) is clearly defined in multiple studies, but studies have failed to find reduction in hard endpoints for stents vs. medical therapy in stable angina patients (see controversies in Percutaneous coronary intervention). The artery-opening stent can temporarily alleviate chest pain, but does not contribute to longevity. The "...vast majority of heart attacks do not originate with obstructions that narrow arteries." Further, “...researchers say, most heart attacks do not occur because an artery is narrowed by plaque. Instead, they say, heart attacks occur when an area of plaque bursts, a clot forms over the area and blood flow is abruptly blocked. In 75 to 80 percent of cases, the plaque that erupts was not obstructing an artery and would not be stented or bypassed. The dangerous plaque is soft and fragile, produces no symptoms and would not be seen as an obstruction to blood flow.”[10]

A more permanent and successful way to prevent heart attacks in patients at high risk is to give up smoking, to exercise regularly, and take "drugs to get blood pressure under control, drive cholesterol levels down and prevent blood clotting".[10]

Some cardiologists believe that stents are overused; however, in certain patient groups, such as the elderly, GRACE and other studies have found evidence of under-use. One cardiologist was convicted of billing patients for performing medically unnecessary stenting.[11][12] Guidelines recommend a stress test before implanting stents, but most patients do not receive a stress test.[13]

Research

While revascularisation (by stenting or bypass surgery) is of clear benefit in reducing mortality and morbidity in patients with acute symptoms (acute coronary syndromes) including myocardial infarction, their benefit is less marked in stable patients. Clinical trials have failed to demonstrate that coronary stents improve survival over best medical treatment.

- The COURAGE trial compared PCI with optimum medical therapy. Of note, the trial excluded a large number of patients at the outset and undertook angiography in all patients at baseline, thus the results only apply to a subset of patients and should not be over-generalised. COURAGE concluded that in patients with stable coronary artery disease PCI did not reduce the death, myocardial infarction or other major cardiac events when added to optimum medical therapy.[14]

- The MASS-II trial compared PCI, CABG and optimum medical therapy for the treatment of multi-vessel coronary artery disease. The MASS-II trial showed no difference in cardiac death or acute MI among patients in the CABG, PCI, or MT group. However, it did show a significantly greater need for additional revascularization procedures in patients who underwent PCI.[15][16]

- The SYNTAX Trial[17] is a manufacturer-funded trial with a primary endpoint of death, cardiovascular events, and myocardial infarction, and also the need for repeat vascularization, in patients with blocked or narrowed arteries. Patients were randomized to either CABG surgery or a drug-eluting stent (the Boston Scientific TAXUS paclitaxel-eluting stent). SYNTAX found the two strategies to be similar for hard endpoints (death and MI). Those receiving PCI required more repeat revascularisation (hence the primary endpoint analysis did not find PCI to be non-inferior), but those undergoing CABG had significantly more strokes pre or perioperatively. Use of the SYNTAX risk score is being investigated as a method of identifying those multivessel disease patients in whom PCI is a reasonable option vs those in whom CABG remains the preferred strategy.

- Ischemia, a large trial of 5,179 participants followed for a median of three and a half years that was funded by the US federal government, was skeptical of the benefits of coronary stents.[18] It divided participants into ones which received drug therapy alone, and those that also received bypass surgery or stents. The drug therapy alone group did not fare any differently than the group that received the stents as well as drug therapy. Ischemia did find that stents seemed to help some patients with angina, however.[19]

Several other clinical trials have been performed to examine the efficacy of coronary stenting and compare with other treatment options. A consensus of the medical community does not exist.

History

The first stent was patented in 1972 by Robert A. Ersek, MD based on work he had done in animals in 1969 at the University of Minnesota. In addition to intervascular stents, he also developed the first stent-supported porcine valve that can be implanted transcutaneously in 7 minutes, eliminating open-heart surgery.[20]

In development are stents with biocompatible surface coatings which do not elute drugs, and also absorbable stents (metal or polymer).

References

- Braunwald's heart disease : a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. Zipes, Douglas P.,, Libby, Peter,, Bonow, Robert O.,, Mann, Douglas L.,, Tomaselli, Gordon F.,, Braunwald, Eugene, 1929- (Eleventh ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9780323555937. OCLC 1021152059.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Armstrong P; WEST Steering Committee (2006). "A comparison of pharmacologic therapy with/without timely coronary intervention vs. primary percutaneous intervention early after ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the WEST (Which Early ST-elevation myocardial infarction Therapy) study". Eur Heart J. 27 (10): 1530–1538. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehl088. PMID 16757491.

- Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. Brunton, Laurence L.,, Knollmann, Björn C.,, Hilal-Dandan, Randa, (Thirteenth ed.). [New York]. ISBN 9781259584732. OCLC 994570810.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: others (link)

- Intravascular Ultrasound - Angioplasty.Org

- Aoki J, Ong ATL, Granillo GAR, McFadden EP, van Mieghem CAG, Valgimigli M, Tsuchida K, Sianos G, Regar E, de Jaegere PPT, van der Giessen WJ, de Feyter PJ, van Domburg RT, Serruys PW (November 2005). ""Full metal jacket" (stented length > or =64 mm) using drug-eluting stents for de novo coronary artery lesions". Am Heart J. 150 (5): 994–9. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2005.01.050. PMID 16290984.

- Angioplasty 101 Angioplasty.Org

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-12-05. Retrieved 2010-09-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Stents | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-11-01.

- Michel, Thomas (2006) [1941]. "Treatment of Myocardial Ischemia". In Laurence L. Brunton; John S. Lazo; Keith L. Parker (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 842.

- Kolata, Gina. "New Heart Studies Question the Value Of Opening Arteries" The New York Times, March 21, 2004. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- David Armstrong (24 October 2013). "The Cardiologist Who Spread Heart Disease". Bloomberg.

- Peter Waldman; David Armstrong & Sydney P. Freedberg (26 September 2013). "Deaths Linked to Cardiac Stents Rise as Overuse Seen". Bloomberg.

- A simple health care fix fizzles out, Kenneth J. Winstein, Wall Street Journal, Feb. 11, 2010.

- Boden WE; O'Rourke RA; Teo KK; Hartigan PM; Maron DJ; Kostuk WJ; Knudtson M; Dada M; Casperson P; Harris CL; Chaitman BR; Shaw L; Gosselin G; Nawaz S; Title LM; Gau G; Blaustein AS; Booth DC; Bates ER; Spertus JA; Berman DS; Mancini GB; Weintraub WS; COURAGE Trial Research Group (2007-04-12). "Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease". N Engl J Med. 356 (15): 1503–16. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa070829. PMID 17387127.

- Hueb W, Soares PR, Gersh BJ, César LA, Luz PL, Puig LB, Martinez EM, Oliveira SA, Ramires JA (2004-05-19). "The medicine, angioplasty, or surgery study (MASS-II): a randomized, controlled clinical trial of three therapeutic strategies for multivessel coronary artery disease: one-year results". J Am Coll Cardiol. 43 (10): 1743–51. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.065. PMID 15145093.

- http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/circulationaha;115/9/1082 MASS-II 5yr follow-up.

- Clinical trial number NCT00114972 at ClinicalTrials.gov SYNTAX trial 2005-2008

- International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness With Medical and Invasive Approaches - ISCHEMIA

- Surgery for Blocked Arteries Is Often Unwarranted, Researchers Find

- https://www.google.com/patents/US3657744