Contrast-enhanced ultrasound

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) is the application of ultrasound contrast medium to traditional medical sonography. Ultrasound contrast agents rely on the different ways in which sound waves are reflected from interfaces between substances. This may be the surface of a small air bubble or a more complex structure. Commercially available contrast media are gas-filled microbubbles that are administered intravenously to the systemic circulation. Microbubbles have a high degree of echogenicity (the ability of an object to reflect ultrasound waves). There is a great difference in echogenicity between the gas in the microbubbles and the soft tissue surroundings of the body. Thus, ultrasonic imaging using microbubble contrast agents enhances the ultrasound backscatter, (reflection) of the ultrasound waves, to produce a sonogram with increased contrast due to the high echogenicity difference. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound can be used to image blood perfusion in organs, measure blood flow rate in the heart and other organs, and for other applications.

Targeting ligands that bind to receptors characteristic of intravascular diseases can be conjugated to microbubbles, enabling the microbubble complex to accumulate selectively in areas of interest, such as diseased or abnormal tissues. This form of molecular imaging, known as targeted contrast-enhanced ultrasound, will only generate a strong ultrasound signal if targeted microbubbles bind in the area of interest. Targeted contrast-enhanced ultrasound may have many applications in both medical diagnostics and medical therapeutics. However, the targeted technique has not yet been approved by the FDA for clinical use in the United States.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound is regarded as safe in adults, comparable to the safety of MRI contrast agents, and better than radiocontrast agents used in contrast CT scans. The more limited safety data in children suggests that such use is as safe as in the adult population.[2]

Bubble echocardiogram

An echocardiogram is a study of the heart using ultrasound. A bubble echocardiogram is an extension of this that uses simple air bubbles as a contrast medium during this study and often has to be requested specifically.

Although colour Doppler can be used to detect abnormal flows between the chambers of the heart (e.g., persistent (patent) foramen ovale), it has a limited sensitivity. When specifically looking for a defect such as this, small air bubbles can be used as a contrast medium and injected intravenously, where they travel to the right side of the heart. The test would be positive for an abnormal communication if the bubbles are seen passing into the left side of the heart. (Normally, they would exit the heart through the pulmonary artery and be stopped by the lungs.) This form of bubble contrast medium is generated on an ad hoc basis by the testing clinician by agitating normal saline (e.g., by rapidly and repeatedly transferring the saline between two connected syringes) immediately prior to injection.

Microbubble contrast agents

General features

There are a variety of microbubble contrast agents. Microbubbles differ in their shell makeup, gas core makeup, and whether or not they are targeted.

- Microbubble shell: selection of shell material determines how easily the microbubble is taken up by the immune system. A more hydrophilic material tends to be taken up more easily, which reduces the microbubble residence time in the circulation. This reduces the time available for contrast imaging. The shell material also affects microbubble mechanical elasticity. The more elastic the material, the more acoustic energy it can withstand before bursting.[3] Currently, microbubble shells are composed of albumin, galactose, lipid, or polymers.[4]

- Microbubble gas core: The gas core is the most important part of the ultrasound contrast microbubble because it determines the echogenicity. When gas bubbles are caught in an ultrasonic frequency field, they compress, oscillate, and reflect a characteristic echo- this generates the strong and unique sonogram in contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Gas cores can be composed of air, or heavy gases like perfluorocarbon, or nitrogen.[4] Heavy gases are less water-soluble so they are less likely to leak out from the microbubble leading to microbubble dissolution.[3] As a result, microbubbles with heavy gas cores last longer in circulation.

Regardless of the shell or gas core composition, microbubble size is fairly uniform. They lie within a range of 1–4 micrometres in diameter. That makes them smaller than red blood cells, which allows them to flow easily through the circulation as well as the microcirculation.

Specific agents

- Sulphur hexafluoride microbubbles (SonoVue Bracco (company)). It is mainly used to characterize liver lesions that cannot be properly identified using conventional (b-mode) ultrasound. It remains visible in the blood for 3 to 8 minutes, and is expired by the lungs.[5]

- Octafluoropropane gas core with an albumin shell ( Optison, a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved microbubble made by GE Healthcare).

- Air within a lipid/galactose shell (Levovist,an FDA-approved microbubble made by Schering).[4]

- Perflexane lipid microspheres (trade name Imagent or previously Imavist) is an injectable suspension developed by Alliance Pharmaceutical approved by the FDA (in June 2002) for improving visualization of the left ventricular chamber of the heart, the delineation of the endocardial borders in patients with suboptimal echocardiograms. Beside its use to assess cardiac function and perfusion it is also used as an enhancer of the images of prostate, liver, kidney and other organs.[6]

- Perflutren lipid microspheres (trade name Definity) are composed of octafluoropropane encapsulated in an outer lipid shell.[7]

Targeted microbubbles

Targeted microbubbles are under preclinical development. They retain the same general features as untargeted microbubbles, but they are outfitted with ligands that bind specific receptors expressed by cell types of interest, such as inflamed cells or cancer cells. Current microbubbles in development are composed of a lipid monolayer shell with a perfluorocarbon gas core. The lipid shell is also covered with a polyethylene glycol (PEG) layer. PEG prevents microbubble aggregation and makes the microbubble more non-reactive. It temporarily “hides” the microbubble from the immune system uptake, increasing the amount of circulation time, and hence, imaging time.[8] In addition to the PEG layer, the shell is modified with molecules that allow for the attachment of ligands that bind certain receptors. These ligands are attached to the microbubbles using carbodiimide, maleimide, or biotin-streptavidin coupling.[8] Biotin-streptavidin is the most popular coupling strategy because biotin's affinity for streptavidin is very strong and it is easy to label the ligands with biotin. Currently, these ligands are monoclonal antibodies produced from animal cell cultures that bind specifically to receptors and molecules expressed by the target cell type. Since the antibodies are not humanized, they will elicit an immune response when used in human therapy. Humanizing antibodies is an expensive and time-intensive process, so it would be ideal to find an alternative source of ligands, such as synthetically manufactured targeting peptides that perform the same function, but without the immune issues.

How it works

There are two forms of contrast-enhanced ultrasound, untargeted (used in the clinic today) and targeted (under preclinical development). The two methods slightly differ from each other.

Untargeted CEUS

Untargeted microbubbles, such as the aforementioned SonoVue, Optison, or Levovist, are injected intravenously into the systemic circulation in a small bolus. The microbubbles will remain in the systemic circulation for a certain period of time. During that time, ultrasound waves are directed on the area of interest. When microbubbles in the blood flow past the imaging window, the microbubbles’ compressible gas cores oscillate in response to the high frequency sonic energy field, as described in the ultrasound article. The microbubbles reflect a unique echo that stands in stark contrast to the surrounding tissue due to the orders of magnitude mismatch between microbubble and tissue echogenicity. The ultrasound system converts the strong echogenicity into a contrast-enhanced image of the area of interest. In this way, the bloodstream's echo is enhanced, thus allowing the clinician to distinguish blood from surrounding tissues.

Targeted CEUS

Targeted contrast-enhanced ultrasound works in a similar fashion, with a few alterations. Microbubbles targeted with ligands that bind certain molecular markers that are expressed by the area of imaging interest are still injected systemically in a small bolus. Microbubbles theoretically travel through the circulatory system, eventually finding their respective targets and binding specifically. Ultrasound waves can then be directed on the area of interest. If a sufficient number of microbubbles have bound in the area, their compressible gas cores oscillate in response to the high frequency sonic energy field, as described in the ultrasound article. The targeted microbubbles also reflect a unique echo that stands in stark contrast to the surrounding tissue due to the orders of magnitude mismatch between microbubble and tissue echogenicity. The ultrasound system converts the strong echogenicity into a contrast-enhanced image of the area of interest, revealing the location of the bound microbubbles.[9] Detection of bound microbubbles may then show that the area of interest is expressing that particular molecular marker, which can be indicative of a certain disease state, or identify particular cells in the area of interest.

Applications

Untargeted contrast-enhanced ultrasound is currently applied in echocardiography and radiology. Targeted contrast-enhanced ultrasound is being developed for a variety of medical applications.

Untargeted CEUS

Untargeted microbubbles like Optison and Levovist are currently used in echocardiography. In addition, SonoVue[10] ultrasound contrast agent is used in radiology for lesion characterization.

- Organ Edge Delineation: microbubbles can enhance the contrast at the interface between the tissue and blood. A clearer picture of this interface gives the clinician a better picture of the structure of an organ. Tissue structure is crucial in echocardiograms, where a thinning, thickening, or irregularity in the heart wall indicates a serious heart condition that requires either monitoring or treatment.

- Blood Volume and Perfusion: contrast-enhanced ultrasound holds the promise for (1) evaluating the degree of blood perfusion in an organ or area of interest and (2) evaluating the blood volume in an organ or area of interest. When used in conjunction with Doppler ultrasound, microbubbles can measure myocardial flow rate to diagnose valve problems. And the relative intensity of the microbubble echoes[11] can also provide a quantitative estimate on blood volume.

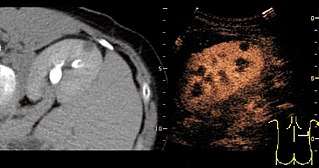

- Lesion Characterization: contrast-enhanced ultrasound plays a role in the differentiation between benign and malignant focal liver lesions. This differentiation relies on the observation[12] or processing[13][14] of the dynamic vascular pattern in a lesion with respect to its surrounding tissue parenchyma.

Targeted CEUS

- Inflammation: Contrast agents may be designed to bind to certain proteins that become expressed in inflammatory diseases such as Crohn's disease, atherosclerosis, and even heart attacks. Cells of interest in such cases are endothelial cells of blood vessels, and leukocytes:

- The inflamed blood vessels specifically express certain receptors, functioning as cell adhesion molecules, like VCAM-1, ICAM-1, E-selectin. If microbubbles are targeted with ligands that bind these molecules, they can be used in contrast echocardiography to detect the onset of inflammation. Early detection allows the design of better treatments. Attempts have been made to outfit microbubbles with monoclonal antibodies that bind P-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1,[4] but the adhesion to the molecular target was poor and a large fraction of microbubbles that bound to the target rapidly detached, especially at high shear stresses of physiological relevance.[15]

- Leukocytes possess high adhesion efficiencies, partly due to a dual-ligand selectin-integrin cell arrest system.[16] One ligand:receptor pair (PSGL-1:selectin) has a fast bond on-rate to slow the leukocyte and allows the second pair (integrin:immunoglobulin superfamily), which has a slower on-rate but slow off-rate to arrest the leukocyte, kinetically enhancing adhesion. Attempts have been made to make contrast agents bind to such ligands, with techniques such as dual-ligand targeting of distinct receptors to polymer microspheres,[17][18] and biomimicry of the leukocyte's selectin-integrin cell arrest system,[19] having shown an increased adhesion efficiency, but yet not efficient enough to allow clinical use of targeted contrast-enhanced ultrasound for inflammation.

- Thrombosis and thrombolysis: Activated platelets are major components of blood clots (thrombi). Microbubbles can be conjugated to a recombinant single-chain variable fragment specific for activated glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GPIIb/IIIa), which is the most abundant platelet surface receptor. Despite the high shear stress at the thrombus area, the GPIIb/IIIa-targeted microbubbles will specifically bind to activated platelets and allow real-time molecular imaging of thrombosis, such as in myocardial infarction, as well as monitoring success or failure of pharmacological thrombolysis.[20]

- Cancer: cancer cells also express a specific set of receptors, mainly receptors that encourage angiogenesis, or the growth of new blood vessels. If microbubbles are targeted with ligands that bind receptors like VEGF, they can non-invasively and specifically identify areas of cancers.

- Gene Delivery: Vector DNA can be conjugated to the microbubbles. Microbubbles can be targeted with ligands that bind to receptors expressed by the cell type of interest. When the targeted microbubble accumulates at the cell surface with its DNA payload, ultrasound can be used to burst the microbubble. The force associated with the bursting may temporarily permeablize surrounding tissues and allow the DNA to more easily enter the cells.

- Drug Delivery: drugs can be incorporated into the microbubble's lipid shell. The microbubble's large size relative to other drug delivery vehicles like liposomes may allow a greater amount of drug to be delivered per vehicle. By targeted the drug-loaded microbubble with ligands that bind to a specific cell type, microbubble will not only deliver the drug specifically, but can also provide verification that the drug is delivered if the area is imaged using ultrasound.

Advantages

On top of the strengths mentioned in the medical sonography entry, contrast-enhanced ultrasound adds these additional advantages:

- The body is 73% water, and therefore, acoustically homogeneous. Blood and surrounding tissues have similar echogenicities, so it is also difficult to clearly discern the degree of blood flow, perfusion, or the interface between the tissue and blood using traditional ultrasound.[4]

- Ultrasound imaging allows real-time evaluation of blood flow.[21]

- Destruction of microbubbles by ultrasound[22] in the image plane allows absolute quantification of tissue perfusion.[23]

- Ultrasonic molecular imaging is safer than molecular imaging modalities such as radionuclide imaging because it does not involve radiation.[21]

- Alternative molecular imaging modalities, such as MRI, PET, and SPECT are very costly. Ultrasound, on the other hand, is very cost-efficient and widely available.[9]

- Since microbubbles can generate such strong signals, a lower intravenous dosage is needed, micrograms of microbubbles are needed compared to milligrams for other molecular imaging modalities such as MRI contrast agents.[9]

- Targeting strategies for microbubbles are versatile and modular. Targeting a new area only entails conjugating a new ligand.

- Active targeting can be increased (enhanced microbubbles adhesion) by Acoustic radiation force[24][25] using a clinical ultrasound imaging system in 2D-mode [26][27] and 3D-mode.[28]

Disadvantages

In addition to the weaknesses mentioned in the medical sonography entry, contrast-enhanced ultrasound suffers from the following disadvantages:

- Microbubbles don't last very long in circulation. They have low circulation residence times because they either get taken up by immune system cells or get taken up by the liver or spleen even when they are coated with PEG.[9]

- Ultrasound produces more heat as the frequency increases, so the ultrasonic frequency must be carefully monitored.

- Microbubbles burst at low ultrasound frequencies and at high mechanical indices (MI), which is the measure of the negative acoustic pressure of the ultrasound imaging system. Increasing MI increases image quality, but there are tradeoffs with microbubble destruction. Microbubble destruction could cause local microvasculature ruptures and hemolysis.[8]

- Targeting ligands can be immunogenic, since current targeting ligands used in preclinical experiments are derived from animal culture.[8]

- Low targeted microbubble adhesion efficiency, which means a small fraction of injected microbubbles bind to the area of interest.[15] This is one of the main reasons that targeted contrast-enhanced ultrasound remains in the preclinical development stages.

See also

- Doppler effect

- Echocardiography

- Medical imaging

- Medical ultrasonography

- Sonography

- Ultrasound

References

- Content initially copied from: Hansen, Kristoffer; Nielsen, Michael; Ewertsen, Caroline (2015). "Ultrasonography of the Kidney: A Pictorial Review". Diagnostics. 6 (1): 2. doi:10.3390/diagnostics6010002. ISSN 2075-4418. PMC 4808817. PMID 26838799. (CC-BY 4.0)

- Sidhu, Paul; Cantisani, Vito; Deganello, Annamaria; Dietrich, Christoph; Duran, Carmina; Franke, Doris; Harkanyi, Zoltan; Kosiak, Wojciech; Miele, Vittorio; Ntoulia, Aikaterini; Piskunowicz, Maciej; Sellars, Maria; Gilja, Odd (2016). "Role of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in Paediatric Practice: An EFSUMB Position Statement". Ultraschall in der Medizin – European Journal of Ultrasound. 38 (1): 33–43. doi:10.1055/s-0042-110394. ISSN 0172-4614. PMID 27414980.

- McCulloch M.; Gresser C.; Moos S.; Odabashian J.; Jasper S.; Bednarz J.; Burgess P.; Carney D.; Moore V.; Sisk E.; Waggoner A.; Witt S.; Adams D. (2000). "Ultrasound contrast physics: A series on contrast echocardiography, article 3". J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 13 (10): 959–67. doi:10.1067/mje.2000.107004. PMID 11029724.

- Lindner J.R. (2004). "Microbubbles in medical imaging: current applications and future directions". Nat Rev Drug Discov. 3 (6): 527–32. doi:10.1038/nrd1417. PMID 15173842.

- "SonoVue, INN-sulphur hexafluoride - Annex I - Summary of Product Characteristics" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- "Perflexane: (AF0150, AFO 150, Imagent, Imavist™)". Drugs in R&D, Volume 3, Number 5, 2002, pp. 306–309(4). Adis International. Retrieved 2010-03-08.

- Rxlist.com > Definity, Last reviewed 6/16/2008

- Klibanov A.L. (2005). "Ligand-carrying gas-filled microbubbles: ultrasound contrast agents for targeted molecular imaging". Bioconjug. Chem. 16 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1021/bc049898y. PMID 15656569.

- Klibanov A.L. (1999). "Targeted delivery of gas-filled microspheres, contrast agents for ultrasound imaging". Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 37 (1–3): 139–157. doi:10.1016/s0169-409x(98)00104-5. PMID 10837732.

- Schneider, M (November 1999). "SonoVue, a new ultrasound contrast agent". Eur. Radiol. 9 (3 Supplement): S347–S348. doi:10.1007/pl00014071. PMID 10602926.

- Rognin, NG; Frinking, P.; Costa, M.; Arditi, M. (November 2008). "In-vivo perfusion quantification by contrast ultrasound: Validation of the use of linearized video data vs. Raw RF data". 2008 IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium. pp. 1690–1693. doi:10.1109/ULTSYM.2008.0413. ISBN 978-1-4244-2428-3.

- Claudon, M; Dietrich, CF.; Choi, BI.; Cosgrove, DO.; Kudo, M.; Nolsøe, CP.; Piscaglia, F.; Wilson, SR.; Barr, RG.; Chammas, MC.; Chaubal, NG.; Chen, MH.; Clevert, DA.; Correas, JM.; Ding, H.; Forsberg, F.; Fowlkes, JB.; Gibson, RN.; Goldberg, BB.; Lassau, N.; Leen, EL.; Mattrey, RF.; Moriyasu, F.; Solbíatí, L.; Weskott, HP.; Xu, HX (February 2013). "Guidelines and Good Clinical Practice Recommendations for Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in the Liver-Update 2012: A WFUMB-EFSUMB Initiative in Cooperation With Representatives of AFSUMB, AIUM, ASUM, FLAUS and ICUS". Ultrasound Med Biol. 39 (2): 187–210. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2012.09.002. PMID 23137926.

- Rognin, NG; Arditi, M.; Mercier, L.; Frinking, P.J.A.; Schneider, M.; Perrenoud, G.; Anaye, A.; Meuwly, J.; Tranquart, F. (November 2010). "Parametric imaging for characterizing focal liver lesions in contrast-enhanced ultrasound". IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control. 57 (11): 2503–2511. doi:10.1109/TUFFC.2010.1716. PMID 21041137.

- Anaye, A; Perrenoud, G.; Rognin, N.; Arditi, M.; Mercier, L.; Frinking, P.; Ruffieux, C.; Peetrons, P.; Meuli, R.; Meuwly, JY. (October 2011). "Differentiation of focal liver lesions: usefulness of parametric imaging with contrast-enhanced US". Radiology. 261 (1): 300–310. doi:10.1148/radiol.11101866. PMID 21746815.

- Takalkar A.M.; Klibanov A.L.; Rychak J.J.; Lindner J.R.; Ley K. (2004). "Binding and detachment dynamics of microbubbles targeted to P-selectin under controlled shear flow". J. Control. Release. 96 (3): 473–482. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.03.002. PMID 15120903.

- Eniola A.O.; Willcox P.J.; Hammer D.A. (2003). "Interplay between rolling and firm adhesion elucidated with a cell-free system engineered with two distinct receptor-ligand pairs". Biophys. J. 85 (4): 2720–31. Bibcode:2003BpJ....85.2720E. doi:10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74695-5. PMC 1303496. PMID 14507735.

- Eniola A.O.; Hammer D.A. (2005). "In vitro characterization of leukocyte mimetic for targeting therapeutics to the endothelium using two receptors". Biomaterials. 26 (34): 7136–44. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.005. PMID 15953632.

- Weller G.E.; Villanueva F.S.; Tom E.M.; Wagner W.R. (2005). "Targeted ultrasound contrast agents: In vitro assessment of endothelial dysfunction and multi-targeting to ICAM-1 and sialyl Lewis(x)". Biotechnol. Bioeng. 92 (6): 780–8. doi:10.1002/bit.20625. PMID 16121392.

- Rychak J.J., A.L. Klibanov, W. Yang, B. Li, S. Acton, A. Leppanen, R.D. Cummings, and K. Ley. "Enhanced Microbubble Adhesion to P-selectin with a Physiologically-tuned Targeting Ligand," 10th Ultrasound Contrast Research Symposium in Radiology, San Diego, CA, March 2005.

- Wang, X; Hagemeyer, CE; Hohmann, JD; Leitner, E; Armstrong, PC; Jia, F; Olschewski, M; Needles, A; Peter, K; Ingo, A (June 2012). "Novel single-chain antibody-targeted microbubbles for molecular ultrasound imaging of thrombosis: Validation of a unique non-invasive method for rapid and sensitive detection of thrombi and monitoring of success or failure of thrombolysis in mice". Circulation. 125 (25): 3117–3126. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.030312. PMID 22647975.

- Lindner, J.R., A.L. Klibanov, and K. Ley. Targeting inflammation, In: Biomedical aspects of drug targeting. (Muzykantov, V.R., Torchilin, V.P., eds.) Kluwer, Boston, 2002; pp. 149–172.

- Wei, K; Jayaweera, AR; Firoozan, S; Linka, A; Skyba, DM; Kaul, S (February 1998). "Quantification of myocardial blood flow with ultrasound-induced destruction of microbubbles administered as a constant venous infusion". Circulation. 97 (5): 473–483. doi:10.1161/01.cir.97.5.473. PMID 9490243.

- Arditi, M; Frinking, PJA.; Zhou, X.; Rognin, NG. (June 2006). "A new formalism for the quantification of tissue perfusion by the destruction-replenishment method in contrast ultrasound imaging". IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control. 53 (6): 1118–1129. doi:10.1109/TUFFC.2006.1642510. PMID 16846144.

- Rychak, JJ; Klibanov, AL; Hossack, JA (March 2005). "Acoustic radiation force enhances targeted delivery of ultrasound contrast microbubbles: in vitro verification". IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control. 52 (3): 421–433. doi:10.1109/TUFFC.2005.1417264. PMID 15857050.

- Dayton, P; Klibanov, A; Brandenburger, G; Ferrara, K (October 1999). "Acoustic radiation force in vivo: a mechanism to assist targeting of microbubbles". Ultrasound Med Biol. 25 (8): 1195–1201. doi:10.1016/s0301-5629(99)00062-9. PMID 10576262.

- Frinking, PJ; Tardy, I; Théraulaz, M; Arditi, M; Powers, J; Pochon, S; Tranquart, F (August 2012). "Effects of acoustic radiation force on the binding efficiency of BR55, a VEGFR2-specific ultrasound contrast agent". Ultrasound Med Biol. 38 (8): 1460–1469. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2012.03.018. PMID 22579540.

- Gessner, RC; Streeter, JE; Kothadia, R; Feingold, S; Dayton, PA (April 2012). "An in vivo validation of the application of acoustic radiation force to enhance the diagnostic utility of molecular imaging using 3-d ultrasound". Ultrasound Med Biol. 38 (4): 651–660. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2011.12.005. PMC 3355521. PMID 22341052.

- Rognin, NG; Unnikrishnan, S.; Klibanov, AL. (September 2013). "Molecular Ultrasound Imaging Enhancement by Volumic Acoustic Radiation Force (VARF): Pre-clinical in vivo Validation in a Murine Tumor Model". Abstracts of the 2013 World Molecular Imaging Congress. Archived from the original on 2013-10-11.

External links

- International Contrast Ultrasound Society International Contrast Ultrasound Society]

- Contrast Echocardiography toolbox, by the EAE association

- Optison Information from GE Healthcare

- Levovist Data Sheet from New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority

- Schering Diagnostics Webpage

- GE Healthcare on Ultrasound Contrast Media

- The American Society of Echocardiography

- The Contrast Zone at the American Society of Echocardiography

- Catalog of Academic Papers related to CEUS

- Targeson, LLC

- SonoVue, Bracco Group