Colestyramine

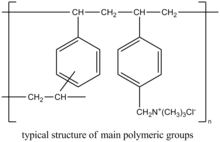

Colestyramine (INN) or cholestyramine (USAN) (trade names Questran, Questran Light, Cholybar, Olestyr) is a bile acid sequestrant, which binds bile in the gastrointestinal tract to prevent its reabsorption. It is a strong ion exchange resin, which means it can exchange its chloride anions with anionic bile acids in the gastrointestinal tract and bind them strongly in the resin matrix. The functional group of the anion exchange resin is a quaternary ammonium group attached to an inert styrene-divinylbenzene copolymer.

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /koʊˈlɛstərəmiːn/, /koʊlɪˈstaɪrəmiːn/ |

| Trade names | Questran Questran Light Cholybar Olestyr |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682672 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | low |

| Protein binding | unknown |

| Metabolism | bile acids |

| Elimination half-life | 1 hour |

| Excretion | Faecal |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.031.143 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Molar mass | In average, exceeds 1×106 g/mol |

| | |

Colestyramine removes bile acids from the body by forming insoluble complexes with bile acids in the intestine, which are then excreted in the feces.[1] As a result of this loss of bile acids, more plasma cholesterol is converted to bile acids in the liver to normalise levels.[1] This conversion of cholesterol into bile acids lowers plasma cholesterol levels.[1]

Medical uses

Bile acid sequestrants such as colestyramine were first used to treat hypercholesterolemia, but since the introduction of statins, now have only a minor role for this indication. They can also be used to treat the pruritus, or itching, that often occurs during liver failure and other types of cholestasis where the ability to eliminate bile acids is reduced.

Colestyramine is commonly used to treat diarrhea resulting from bile acid malabsorption.[2] It was first used for this in Crohn's disease patients who had undergone ileal resection.[3] The terminal portion of the small bowel (ileum) is where bile acids are reabsorbed. When this section is removed, the bile acids pass into the large bowel and cause diarrhea due to stimulation of chloride/fluid secretion by the colonocytes resulting in a secretory diarrhea. Colestyramine prevents this increase in water by making the bile acids insoluble and osmotically inactive.

Colestyramine is also used in the control of other types of bile acid diarrhea. The primary, idiopathic form of bile acid diarrhea is a common cause of chronic functional diarrhea, often misdiagnosed as diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D), and most of these patients respond to colestyramine.[4] It is beneficial in the treatment of postcholecystectomy syndrome chronic diarrhea.[5][6] Colestyramine is also useful in treating post-vagotomy diarrhea.[7][8]

Colestyramine can be helpful in the treatment of Clostridium difficile infections, to absorb toxins A and B, and reduce the diarrhea and the other symptoms these toxins cause. However, because it is not an anti-infective, it is used in concert with vancomycin.[9]

It is also used in the "wash out" procedure in patients taking leflunomide or teriflunomide to aid drug elimination in the case of drug discontinuation due to severe side effects caused by leflunomide or teriflunomide.[10]

A case report suggests that colestyramine may be useful for cyanobacterial (microcystin) poisoning in dogs.[11]

Ointments containing colestyramine compounded with aquaphor have been used in topical treatment of diaper rash in infants and toddlers.[12]

Cholestyramine also binds with oxalate in the GI tract, ultimately reducing urine oxalate and calcium oxalate stone formation.[13]

Available forms

Colestyramine is available as powder form, in 4-g packets, or in larger canisters. In the United States, it can be purchased either as a generic medicine, or as Questran or Questran Light (Bristol-Myers Squibb).

Dosage

A typical dose is 4 to 8 g once or twice daily, with a maximum dose of 24 g/d.

Side effects

These side effects have been noted:[14]

- Most frequent: constipation

- Increased plasma triglycerides[15]

Intestinal obstruction has been reported in patients with previous bowel surgery who should use colestyramine cautiously.[16] [17] Cholestyramine-induced hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis has also been reported rarely.[18]

Patients with hypothyroidism, diabetes, nephrotic syndrome, dysproteinemia, obstructive liver disease, kidney disease, or alcoholism should consult their doctor before taking this medication.[14] Other drugs should be taken at least one hour before or four to six hours after colestyramine to reduce possible interference with absorption. Patients with phenylketonuria should consult with a physician before taking Questran Light because that product contains phenylalanine.

Drug interactions

Interactions with these drugs have been noted:[14]

- Digitalis

- Estrogens and progestins

- Oral diabetes drugs

- Penicillin G

- Phenobarbital

- Spironolactone

- Tetracycline

- Thiazide-type diuretic pills

- Thyroid medication

- Warfarin

- Leflunomide

Most interactions are due to the risk of decreased absorption of these drugs.[17] The duration of treatment is not limited, but the prescribing physician should reassess at regular intervals if continued treatment is still necessary. The principal overdose risk is blockage of intestine or stomach.

Colestyramine may interfere in the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins such as vitamins A, D, E, and K. No special considerations regarding alcohol consumption are made.[14]

Notes and references

- The Merck Index (12 ed.). p. 2257.

- http://livertox.nih.gov/Cholestyramine.htm, United States National Institutes of Health (page visited on 22 June 2016).

- Wilcox C, Turner J, Green J (May 2014). "Systematic review: the management of chronic diarrhoea due to bile acid malabsorption". Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 39 (9): 923–39. doi:10.1111/apt.12684. PMID 24602022.

- Hofmann AF, Poley JR (August 1969). "Cholestyramine treatment of diarrhea associated with ileal resection". N. Engl. J. Med. 281 (8): 397–402. doi:10.1056/NEJM196908212810801. PMID 4894463.

- Wedlake L, A'Hern R, Russell D, Thomas K, Walters JR, Andreyev HJ (October 2009). "Systematic review: the prevalence of idiopathic bile acid malabsorption as diagnosed by SeHCAT scanning in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome". Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 30 (7): 707–17. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04081.x. PMID 19570102.

- Sciarretta G, Furno A, Mazzoni M, Malaguti P (December 1992). "Post-cholecystectomy diarrhea: evidence of bile acid malabsorption assessed by SeHCAT test". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 87 (12): 1852–4. PMID 1449156.

- Danley T, St Anna L (October 2011). "Clinical inquiry. Postcholecystectomy diarrhea: what relieves it?". J Fam Pract. 60 (10): 632c–d. PMID 21977493.

- George, J. D.; Magowan, J. (1971). "Diarrhea after total and selective vagotomy". The American Journal of Digestive Diseases. 16 (7): 635–40. doi:10.1007/BF02239223. PMID 5563217.

- Gorbashko, AI (1992). "The pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of postvagotomy diarrhea". Vestnik Khirurgii Imeni I. I. Grekova. 148 (3): 254–62. PMID 8594740.

- Stroehlein JR (June 2004). "Treatment of Clostridium difficile Infection". Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 7 (3): 235–239. doi:10.1007/s11938-004-0044-y. PMID 15149585.

- Wong SP, Chu CM, Kan CH, Tsui HS, Ng WL (December 2009). "Successful treatment of leflunomide-induced acute pneumonitis with cholestyramine wash-out therapy". J Clin Rheumatol. 15 (8): 389–92. doi:10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181c3f87e. PMID 19955995.

- Rankin KA, Alroy KA, Kudela RM, Oates SC, Murray MJ, Miller MA (2013). "Treatment of cyanobacterial (microcystin) toxicosis using oral cholestyramine: case report of a dog from Montana". Toxins (Basel). 5 (6): 1051–63. doi:10.3390/toxins5061051. PMC 3717769. PMID 23888515.

- White CM, Gailey RA, Lippe S (1996). "Cholestyramine ointment to treat buttocks rash and anal excoriation in an infant". Ann Pharmacother. 30 (9): 954–6. doi:10.1177/106002809603000907. PMID 8876854.

- https://www.nytimes.com/health/guides/disease/kidney-stones/medications.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Questran". PDRHealth. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Triglyceride level

- Merten, DF; Grossman, H (1980). "Intestinal obstruction associated with cholestyramine therapy". American Journal of Roentgenology. 134 (4): 827–8. doi:10.2214/ajr.134.4.827. PMID 6767374.

- Jacobson TA, Armani A, McKenney JM, Guyton JR (2007). "Safety considerations with gastrointestinally active lipid-lowering drugs". Am J Cardiol. 99 (6A): 47C–55C. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.11.022. PMID 17368279.

- Kamar, FB; McQuillan, RF (2015). "Hyperchloremic Metabolic Acidosis due to Cholestyramine: A Case Report and Literature Review". Case Reports in Nephrology. 2015: 309791. doi:10.1155/2015/309791. PMC 4573617. PMID 26425378.