Cleft lip and cleft palate

Cleft lip and cleft palate, also known as orofacial cleft, is a group of conditions that includes cleft lip (CL), cleft palate (CP), and both together (CLP).[1][2] A cleft lip contains an opening in the upper lip that may extend into the nose.[1] The opening may be on one side, both sides, or in the middle.[1] A cleft palate occurs when the roof of the mouth contains an opening into the nose.[1] These disorders can result in feeding problems, speech problems, hearing problems, and frequent ear infections.[1] Less than half the time the condition is associated with other disorders.[1]

| Cleft lip and palate | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hare-lip, cleft lip and palate |

| Child with cleft lip and palate. | |

| Specialty | Otorhinolaryngology, pediatrics |

| Symptoms | Opening in the upper lip that may extend into the nose or palate[1] |

| Complications | Feeding problems, speech problems, hearing problems, frequent ear infections[1] |

| Usual onset | Present at birth[1] |

| Causes | Usually unknown[1] |

| Risk factors | Smoking during pregnancy, diabetes, obesity, older mother, certain medications[1][2] |

| Treatment | Surgery, speech therapy, dental care[1] |

| Prognosis | Good (with treatment)[1] |

| Frequency | 1.5 per 1000 births (developed world)[2] |

| Deaths | 3,800 (2017)[3] |

Cleft lip and palate are the result of tissues of the face not joining properly during development.[1] As such, they are a type of birth defect.[1] The cause is unknown in most cases.[1] Risk factors include smoking during pregnancy, diabetes, obesity, an older mother, and certain medications (such as some used to treat seizures).[1][2] Cleft lip and cleft palate can often be diagnosed during pregnancy with an ultrasound exam.[1]

A cleft lip or palate can be successfully treated with surgery.[1] This is often done in the first few months of life for cleft lip and before eighteen months for cleft palate.[1] Speech therapy and dental care may also be needed.[1] With appropriate treatment, outcomes are good.[1]

Cleft lip and palate occurs in about 1 to 2 per 1000 births in the developed world.[2] CL is about twice as common in males as females, while CP without CL is more common in females.[2] In 2017, it resulted in about 3,800 deaths globally, down from 14,600 deaths in 1990.[3][4] The condition was formerly known as a "hare-lip" because of its resemblance to a hare or rabbit, but that term is now generally considered to be offensive.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Cleft lip

If the cleft does not affect the palate structure of the mouth, it is referred to as cleft lip. Cleft lip is formed in the top of the lip as either a small gap or an indentation in the lip (partial or incomplete cleft), or it continues into the nose (complete cleft). Lip cleft can occur as a one-sided (unilateral) or two-sided (bilateral) condition. It is due to the failure of fusion of the maxillary prominence and medial nasal processes (formation of the primary palate).

Unilateral incomplete

Unilateral incomplete Unilateral complete

Unilateral complete Bilateral complete

Bilateral complete

A mild form of a cleft lip is a microform cleft.[6] A microform cleft can appear as small as a little dent in the red part of the lip or look like a scar from the lip up to the nostril.[7] In some cases muscle tissue in the lip underneath the scar is affected and might require reconstructive surgery.[8] It is advised to have newborn infants with a microform cleft checked with a craniofacial team as soon as possible to determine the severity of the cleft.[9]

Six-month-old girl before going into surgery to have her unilateral complete cleft lip repaired

Six-month-old girl before going into surgery to have her unilateral complete cleft lip repaired The same girl, 1 month after the surgery

The same girl, 1 month after the surgery The same girl, age 8, the scar almost gone

The same girl, age 8, the scar almost gone

Cleft palate

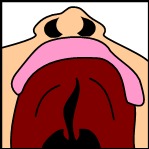

Cleft palate is a condition in which the two plates of the skull that form the hard palate (roof of the mouth) are not completely joined. The soft palate is in these cases cleft as well. In most cases, cleft lip is also present.

Palate cleft can occur as complete (soft and hard palate, possibly including a gap in the jaw) or incomplete (a 'hole' in the roof of the mouth, usually as a cleft soft palate). When cleft palate occurs, the uvula is usually split. It occurs due to the failure of fusion of the lateral palatine processes, the nasal septum, or the median palatine processes (formation of the secondary palate).

The hole in the roof of the mouth caused by a cleft connects the mouth directly to the inside of the nose.

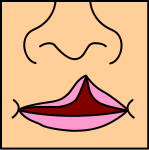

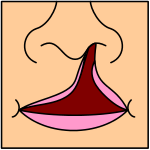

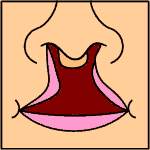

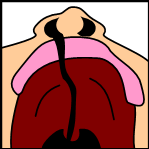

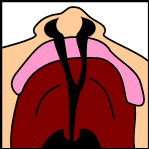

Note: the next images show the roof of the mouth. The top shows the nose, the lips are colored pink. For clarity the images depict a toothless infant.

Incomplete cleft palate

Incomplete cleft palate Unilateral complete lip and palate

Unilateral complete lip and palate Bilateral complete lip and palate

Bilateral complete lip and palate

A result of an open connection between the mouth and inside the nose is called velopharyngeal inadequacy (VPI). Because of the gap, air leaks into the nasal cavity resulting in a hypernasal voice resonance and nasal emissions while talking.[10] Secondary effects of VPI include speech articulation errors (e.g., distortions, substitutions, and omissions) and compensatory misarticulations and mispronunciations (e.g., glottal stops and posterior nasal fricatives).[11] Possible treatment options include speech therapy, prosthetics, augmentation of the posterior pharyngeal wall, lengthening of the palate, and surgical procedures.[10]

Submucous cleft palate (SMCP) can also occur, which is a cleft of the soft palate with a split uvula, a furrow along the midline of the soft palate, and a notch in the back margin of the hard palate.[12] The diagnosis of SMCP often occurs late in children as a result of the nature of the cleft.[13] While the muscles of the soft palate are not joined, the mucosal membranes covering the roof of the mouth appear relatively normal and intact.[14]

Psychosocial issues

Most children who have their clefts repaired early enough are able to have a happy youth and social life. Having a cleft palate/lip does not inevitably lead to a psychosocial problem. However, adolescents with cleft palate/lip are at an elevated risk for developing psychosocial problems especially those relating to self-concept, peer relationships and appearance. Adolescents may face psychosocial challenges but can find professional help if problems arise. A cleft palate/lip may impact an individual's self-esteem, social skills and behavior. There is research dedicated to the psychosocial development of individuals with cleft palate. Self-concept may be adversely affected by the presence of a cleft lip or cleft palate, particularly among girls.[15]

Research has shown that during the early preschool years (ages 3–5), children with cleft lip or cleft palate tend to have a self-concept that is similar to their peers without a cleft. However, as they grow older and their social interactions increase, children with clefts tend to report more dissatisfaction with peer relationships and higher levels of social anxiety. Experts conclude that this is probably due to the associated stigma of visible deformities and possible speech impediments. Children who are judged as attractive tend to be perceived as more intelligent, exhibit more positive social behaviors, and are treated more positively than children with cleft lip or cleft palate.[16] Children with clefts tend to report feelings of anger, sadness, fear, and alienation from their peers, but these children were similar to their peers in regard to "how well they liked themselves."

The relationship between parental attitudes and a child's self-concept is crucial during the preschool years. It has been reported that elevated stress levels in mothers correlated with reduced social skills in their children.[17] Strong parent support networks may help to prevent the development of negative self-concept in children with cleft palate.[18] In the later preschool and early elementary years, the development of social skills is no longer only impacted by parental attitudes but is beginning to be shaped by their peers. A cleft lip or cleft palate may affect the behavior of preschoolers. Experts suggest that parents discuss with their children ways to handle negative social situations related to their cleft lip or cleft palate. A child who is entering school should learn the proper (and age-appropriate) terms related to the cleft. The ability to confidently explain the condition to others may limit feelings of awkwardness and embarrassment and reduce negative social experiences.[19]

As children reach adolescence, the period of time between age 13 and 19, the dynamics of the parent-child relationship change as peer groups are now the focus of attention. An adolescent with cleft lip or cleft palate will deal with the typical challenges faced by most of their peers including issues related to self-esteem, dating and social acceptance.[20][21][22] Adolescents, however, view appearance as the most important characteristic, above intelligence and humor.[23] This being the case, adolescents are susceptible to additional problems because they cannot hide their facial differences from their peers. Adolescent boys typically deal with issues relating to withdrawal, attention, thought, and internalizing problems, and may possibly develop anxiousness-depression and aggressive behaviors.[22] Adolescent girls are more likely to develop problems relating to self-concept and appearance. Individuals with cleft lip or cleft palate often deal with threats to their quality of life for multiple reasons including: unsuccessful social relationships, deviance in social appearance and multiple surgeries.

Complications

Cleft may cause problems with feeding, ear disease, speech, socialization, and cognition.

Due to lack of suction, an infant with a cleft may have trouble feeding. An infant with a cleft palate will have greater success feeding in a more upright position. Gravity will help prevent milk from coming through the baby's nose if he/she has cleft palate. Gravity feeding can be accomplished by using specialized equipment, such as the Haberman Feeder. Another equipment commonly used for gravity feeding is a customized bottle with a combination of nipples and bottle inserts. A large hole, crosscut, or slit in the nipple, a protruding nipple and rhythmically squeezing the bottle insert can result in controllable flow to the infant without the stigma caused by specialized equipment.

Individuals with cleft also face many middle ear infections which may eventually lead to hearing loss. The Eustachian tubes and external ear canals may be angled or tortuous, leading to food or other contamination of a part of the body that is normally self-cleaning. Hearing is related to learning to speak. Babies with palatal clefts may have compromised hearing and therefore, if the baby cannot hear, it cannot try to mimic the sounds of speech. Thus, even before expressive language acquisition, the baby with the cleft palate is at risk for receptive language acquisition. Because the lips and palate are both used in pronunciation, individuals with cleft usually need the aid of a speech therapist.

Tentative evidence has found that those with clefts perform less well at language.[24]

Cause

The development of the face is coordinated by complex morphogenetic events and rapid proliferative expansion, and is thus highly susceptible to environmental and genetic factors, rationalising the high incidence of facial malformations. During the first six to eight weeks of pregnancy, the shape of the embryo's head is formed. Five primitive tissue lobes grow:

- a) one from the top of the head down towards the future upper lip (frontonasal prominence);

- b-c) two from the cheeks, which meet the first lobe to form the upper lip (maxillar prominence);

- d-e) and just below, two additional lobes grow from each side, which form the chin and lower lip (mandibular prominence).

If these tissues fail to meet, a gap appears where the tissues should have joined (fused). This may happen in any single joining site, or simultaneously in several or all of them. The resulting birth defect reflects the locations and severity of individual fusion failures (e.g., from a small lip or palate fissure up to a completely malformed face).

The upper lip is formed earlier than the palate, from the first three lobes named a to c above. Formation of the palate is the last step in joining the five embryonic facial lobes, and involves the back portions of the lobes b and c. These back portions are called palatal shelves, which grow towards each other until they fuse in the middle.[25] This process is very vulnerable to multiple toxic substances, environmental pollutants, and nutritional imbalance. The biologic mechanisms of mutual recognition of the two cabinets, and the way they are glued together, are quite complex and obscure despite intensive scientific research.[26]

Orofacial clefts may be associated with a syndrome (syndromic) or may not be associated with a syndrome (nonsyndromic). Syndromic clefts are part of syndromes that are caused by a variety of factors such as environment and genetics or an unknown cause. Nonsyndromic clefts, which are not as common as syndromic clefts, also have a genetic cause.[27]

Genetics

Genetic factors contributing to cleft lip and cleft palate formation have been identified for some syndromic cases. Many clefts run in families, even though in some cases there does not seem to be an identifiable syndrome present.[28] A number of genes are involved including cleft lip and palate transmembrane protein 1 and GAD1,[29] One study found an association between mutations in the HYAL2 gene and cleft lip and cleft palate formation.[30]

Syndromes

- The Van der Woude Syndrome is caused by a specific variation in the gene IRF6 that increases the occurrence of these deformities threefold.[31][32][33]

- Another syndrome, Siderius X-linked intellectual disability, is caused by mutations in the PHF8 gene (OMIM 300263); in addition to cleft lip or palate, symptoms include facial dysmorphism and mild mental retardation.[34]

In some cases, cleft palate is caused by syndromes that also cause other problems:

- Stickler's Syndrome can cause cleft lip and palate, joint pain, and myopia.[35][36]

- Loeys-Dietz syndrome can cause cleft palate or bifid uvula, hypertelorism, and aortic aneurysm.[37]

- Hardikar syndrome can cause cleft lip and palate, Hydronephrosis, Intestinal obstruction and other symptoms.[38]

- Cleft lip/palate may be present in many different chromosome disorders including Patau Syndrome (trisomy 13).

- Malpuech facial clefting syndrome

- Hearing loss with craniofacial syndromes

- Popliteal pterygium syndrome

- Treacher Collins syndrome

- Pierre Robin syndrome[39][40]

Specific genes

| Type | OMIM | Gene | Locus |

|---|---|---|---|

| OFC1 | 119530 | ? | 6p24 |

| OFC2 | 602966 | ? | 2p13 |

| OFC3 | 600757 | ? | 19q13 |

| OFC4 | 608371 | ? | 4q |

| OFC5 | 608874 | MSX1 | 4p16.1 |

| OFC6 | 608864 | ? | 1q |

| OFC7 | 600644) | PVRL1 | 11q |

| OFC8 | 129400 | TP63 | 3q27 |

| OFC9 | 610361 | ? | 13q33.1-q34 |

| OFC10 | 601912 | SUMO1 | 2q32.2-q33 |

| OFC11 | 600625 | BMP4 | 14q22 |

| OFC12 | 612858 | ? | 8q24.3 |

Many genes associated with syndromic cases of cleft lip/palate (see above) have been identified to contribute to the incidence of isolated cases of cleft lip/palate. This includes in particular sequence variants in the genes IRF6, PVRL1 and MSX1.[41] The understanding of the genetic complexities involved in the morphogenesis of the midface, including molecular and cellular processes, has been greatly aided by research on animal models, including of the genes BMP4, SHH, SHOX2, FGF10 and MSX1.[41]

Environmental factors

Environmental influences may also cause, or interact with genetics to produce, orofacial clefts. An example of the link between environmental factors and genetics comes from a research on mutations in the gene PHF8. The research found that PHF8 encodes for a histone lysine demethylase,[42] and is involved in epigenetic regulation. The catalytic activity of PHF8 depends on molecular oxygen,[42] a factor considered important from reports on increased incidence of cleft lip/palate in mice that have been exposed to hypoxia early during pregnancy.[43]

Cleft lip and other congenital abnormalities have also been linked to maternal hypoxia caused by maternal smoking,[44] maternal alcohol abuse, or some forms of maternal hypertension treatment.[45] Other environmental factors that have been studied include: seasonal causes (such as pesticide exposure); maternal diet and vitamin intake; retinoids (members of the vitamin A family); anticonvulsant drugs; nitrate compounds; organic solvents; parental exposure to lead; alcohol; cigarette use; and a number of other psychoactive drugs (e.g. cocaine, crack cocaine, heroin).

Current research continues to investigate the extent to which folic acid can reduce the incidence of clefting.[46]

Diagnosis

Traditionally, the diagnosis is made at the time of birth by physical examination. Recent advances in prenatal diagnosis have allowed obstetricians to diagnose facial clefts in utero with ultrasonography.[47]

Clefts can also affect other parts of the face, such as the eyes, ears, nose, cheeks, and forehead. In 1976, Paul Tessier described fifteen lines of cleft. Most of these craniofacial clefts are even rarer and are frequently described as Tessier clefts using the numerical locator devised by Tessier.[48]

Classification

Cleft lip and cleft palate is an "umbrella term" for a collection of orofacial clefts. It includes clefting of the upper lip, the maxillary alveolus (dental arch), and the hard or soft palate, in various combinations. Proposed anatomic combinations include:[49]

- cleft lip [CL]

- cleft lip and alveolus [CLA]

- cleft lip, alveolus, and palate [CLAP]

- cleft lip and palate (with an intact alveolus) [CLP]

- cleft palate [CP]

Treatment

Cleft lip and palate is very treatable; however, the kind of treatment depends on the type and severity of the cleft.

Most children with a form of clefting are monitored by a cleft palate team or craniofacial team through young adulthood.[50] Care can be lifelong. Treatment procedures can vary between craniofacial teams. For example, some teams wait on jaw correction until the child is aged 10 to 12 (argument: growth is less influential as deciduous teeth are replaced by permanent teeth, thus saving the child from repeated corrective surgeries), while other teams correct the jaw earlier (argument: less speech therapy is needed than at a later age when speech therapy becomes harder). Within teams, treatment can differ between individual cases depending on the type and severity of the cleft.

Cleft lip

Within the first 2–3 months after birth, surgery is performed to close the cleft lip. While surgery to repair a cleft lip can be performed soon after birth, often the preferred age is at approximately 10 weeks of age, following the "rule of 10s" coined by surgeons Wilhelmmesen and Musgrave in 1969 (the child is at least 10 weeks of age; weighs at least 10 pounds, and has at least 10g hemoglobin).[51][52] If the cleft is bilateral and extensive, two surgeries may be required to close the cleft, one side first, and the second side a few weeks later. The most common procedure to repair a cleft lip is the Millard procedure pioneered by Ralph Millard. Millard performed the first procedure at a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) unit in Korea.[53]

Often an incomplete cleft lip requires the same surgery as complete cleft. This is done for two reasons. Firstly the group of muscles required to purse the lips run through the upper lip. In order to restore the complete group a full incision must be made. Secondly, to create a less obvious scar the surgeon tries to line up the scar with the natural lines in the upper lip (such as the edges of the philtrum) and tuck away stitches as far up the nose as possible. Incomplete cleft gives the surgeon more tissue to work with, creating a more supple and natural-looking upper lip.

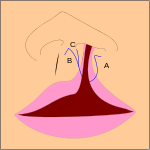

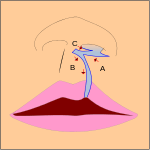

The blue lines indicate incisions.

The blue lines indicate incisions. Movement of the flaps; flap A is moved between B and C. C is rotated slightly while B is pushed down.

Movement of the flaps; flap A is moved between B and C. C is rotated slightly while B is pushed down. Pre-operation

Pre-operation Post-operation, the lip is swollen from surgery and will get a more natural look within a couple of weeks. See photos in the section above.

Post-operation, the lip is swollen from surgery and will get a more natural look within a couple of weeks. See photos in the section above.

Pre-surgical devices

In some cases of a severe bi-lateral complete cleft, the premaxillary segment will be protruded far outside the mouth.

Nasoalveolar molding prior to surgery can improve long-term nasal symmetry among patients with complete unilateral cleft lip–cleft palate patients compared to correction by surgery alone, according to a retrospective cohort study.[54] In this study, significant improvements in nasal symmetry were observed in multiple areas including measurements of the projected length of the nasal ala (lateral surface of the external nose), position of the superoinferior alar groove, position of the mediolateral nasal dome, and nasal bridge deviation. "The nasal ala projection length demonstrated an average ratio of 93.0 percent in the surgery-alone group and 96.5 percent in the nasoalveolar molding group," this study concluded.

Cleft palate

Often a cleft palate is temporarily covered by a palatal obturator (a prosthetic device made to fit the roof of the mouth covering the gap).

Cleft palate can also be corrected by surgery, usually performed between 6 and 12 months. Approximately 20–25% only require one palatal surgery to achieve a competent velopharyngeal valve capable of producing normal, non-hypernasal speech. However, combinations of surgical methods and repeated surgeries are often necessary as the child grows. One of the new innovations of cleft lip and cleft palate repair is the Latham appliance.[55] The Latham is surgically inserted by use of pins during the child's 4th or 5th month. After it is in place, the doctor, or parents, turn a screw daily to bring the cleft together to assist with future lip or palate repair.

If the cleft extends into the maxillary alveolar ridge, the gap is usually corrected by filling the gap with bone tissue. The bone tissue can be acquired from the patients own chin, rib or hip.

Speech

Children with cleft palate are at risk for having velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI). Velopharyngeal insufficiency refers to the inability of the soft palate to elevate and then close against the back wall of the throat during speech. This is usually because, despite the palate repair, the soft palate is too short to reach the back of the throat and close tightly against it. Velopharyngeal closure is necessary during speech because it closes off the nose from the mouth. This allows the air from the lungs and sound from the voice box to enter the mouth for normal speech. Velopharyngeal insufficiency can cause hypernasality (too much sound in the nasal cavity during speech) or audible nasal emission of the air stream. The lack of adequate airflow in the mouth can make the production of many speech sounds, (i.e., /p/, /b/, /t/, /d/, /s/, /z/, etc.) very difficult or impossible to produce.[56][57]

Because of the lack of adequate airflow in the mouth for speech, children with cleft palate often compensate by producing speech sounds in the pharynx (throat area) where there is airflow. These speech errors improve intelligibility somewhat, but will require speech therapy for correction after surgical correction of VPI is done [56][58][59]

Velopharyngeal insufficiency is a disorder of abnormal structure. Therefore, correction of VPI requires surgical intervention, or a prosthetic device in rare cases when surgery is not an option. Although speech therapy cannot correct VPI (including the hypernasality and/or audible nasal emission that occurs from VPI), therapy is often needed after VPI surgery to correct compensatory errors that develop as a result of VPI. Speech outcomes are usually better with surgical correction of VPI and necessary therapy in the preschool years.[60]

Hearing

Children with cleft palate are at increased risk for conductive hearing loss.[61] This is caused by negative pressure and fluid buildup in the middle ear as a result of poor development of the tensor veli palatini muscle. This muscle is responsible for opening the eustachian tube to allow drainage of the middle ear. A tympanostomy tube is often inserted into the eardrum to aerate the middle ear.[62] This is often beneficial for the hearing of the child.[63]

Sample treatment schedule

Each person's schedule is individualized. The table below shows a common sample treatment schedule. The colored squares indicate the average timeframe in which the indicated procedure occurs. In some cases this is usually one procedure (for example lip repair); in other cases this is an ongoing therapy (for example speech therapy) and in most cases of cleft lip and palate that involve the alveolus bone people will need a treatment plan including prevention of cavities, orthodontics, alevolar bone grafting, and possibly jaw surgery.[64][65]

| Age | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Palatal obturator | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Repair cleft lip | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Repair soft palate | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Repair hard palate | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tympanostomy tube | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speech therapy/pharyngoplasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alveolar cleft grafting | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Orthodontics | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Orthognathic surgery |

Craniofacial team

A craniofacial team is routinely used to treat this condition. The majority of hospitals still use craniofacial teams; yet others are making a shift towards dedicated cleft lip and palate programs. While craniofacial teams are widely knowledgeable about all aspects of craniofacial conditions, dedicated cleft lip and palate teams are able to dedicate many of their efforts to being on the cutting edge of new advances in cleft lip and palate care.

Many of the top pediatric hospitals are developing their own CLP clinics in order to provide patients with comprehensive multi-disciplinary care from birth through adolescence. Allowing an entire team to care for a child throughout their cleft lip and palate treatment (which is ongoing) allows for the best outcomes in every aspect of a child's care. While the individual approach can yield significant results, current trends indicate that team based care leads to better outcomes for CLP patients. .[66]

Outcomes assessment

Outcomes assessment in CL/P has been laden with difficulty due to the complexity and longitudinal nature of cleft care (which spans birth through young adulthood). Pioneering efforts at outcomes comparisons between treatment protocols or between centers include the Eurocleft, CSAG, Americleft, and Scandcleft projects. One of the major limitations identified by these projects was the lack of data standards for outcomes assessment in cleft care.[67]

Recently, the International Consortium for Health Outcome Measurement (ICHOM) proposed the Standard Set of Outcome Measures for Cleft Lip/Palate,[68][69] which was developed in accordance with the guidelines of the WHO International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF).[70] The ICHOM Standard Set includes measures for many of the important outcome domains in cleft care (hearing, breathing, eating/drinking, speech, oral health, appearance, psychosocial well-being, and team-based process metrics), and it includes clinician-reported, patient-reported, and family-reported outcome measures. The ICHOM Standard Set is considered open source (CC-BY-SA).

Epidemiology

Cleft lip and palate occurs in about 1 to 2 per 1000 births in the developed world.[2]

Rates for cleft lip with or without cleft palate and cleft palate alone varies within different ethnic groups.

According to CDC, the prevalence of cleft palate in the United States is 6.35/10000 births and the prevalence of cleft lip with or without cleft palate is 10.63/10000 births.[71] The highest prevalence rates for (CL ± P) are reported for Native Americans and Asians. Africans have the lowest prevalence rates.[72]

- Native Americans: 3.74/1000

- Japanese: 0.82/1000 to 3.36/1000

- Chinese: 1.45/1000 to 4.04/1000

- Caucasians: 1.43/1000 to 1.86/1000

- Latin Americans: 1.04/1000

- Africans: 0.18/1000 to 1.67/1000

Cleft lip and cleft palate caused about 3,800 deaths globally in 2017, down from 14,600 deaths in 1990.[4]

Prevalence of "cleft uvula" has varied from 0.02% to 18.8% with the highest numbers found among Chippewa and Navajo and the lowest generally in Africans.[73][74]

Society and culture

Abortion controversy

In some countries, cleft lip or palate deformities are considered reasons (either generally tolerated or officially sanctioned) to perform an abortion beyond the legal fetal age limit, even though the fetus is not in jeopardy of life or limb. Some human rights activists contend that this practice of what they refer to as "cosmetic murder" amounts to eugenics.

Works of fiction

The eponymous hero of J.M. Coetzee's 1983 novel Life & Times of Michael K has a cleft lip that is never corrected. In the 1920 novel Growth of the Soil, by Norwegian writer Knut Hamsun, Inger (wife of the main character) has an uncorrected cleft lip which puts heavy limitations on her life, even causing her to kill her own child, who is also born with a cleft lip. The protagonist of the 1924 novel Precious Bane, by English writer Mary Webb, is a young woman living in 19th-century rural Shropshire who eventually comes to feel that her deformity is the source of her spiritual strength. The book was later adapted for television by both the BBC and ORTF in France.

In Inheritance, the final title of Christopher Paolini's Inheritance Cycle, the main character Eragon heals a newborn girl with this condition in a display of complicated healing magic. It is stated that those within Eragon's society born with this condition are often not allowed to live as they face a very hard life.[75]

Cleft lip and cleft palate are often portrayed negatively in popular culture. Examples include Oddjob, the secondary villain of the James Bond novel Goldfinger by Ian Fleming (the film adaptation does not mention this but leaves it implied); the fanciful portrayal of Roman Emperor Commodus in the 2000 film Gladiator;[76] and serial killer Francis Dolarhyde in the novel Red Dragon and its film adaptations, Manhunter and Red Dragon.[77] The portrayal of enemy characters with cleft lips and cleft palates, dubbed mutants, in the 2019 video game Rage 2 left Chris Plante of Polygon wondering if the condition would ever be portrayed positively.[78][79]

Notable cases

| Name | Comments | |

|---|---|---|

| Jerry Byrd | American sportswriter for the Shreveport Journal, 1957-1991, and Bossier Press-Tribune, 1993-2012; born with cleft lip and without cleft palate | [80] |

| John Henry "Doc" Holliday | American dentist, gambler and gunfighter of the American Old West, who is usually remembered for his friendship with Wyatt Earp and the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral | [81] |

| Tutankhamen | Egyptian pharaoh who may have had a slightly cleft palate according to diagnostic imaging | [82] |

| Thorgils Skarthi | Thorgils 'the hare-lipped'—a 10th-century Viking warrior and founder of Scarborough, England. | [83] |

| Tad Lincoln | Fourth and youngest son of President Abraham Lincoln | [84] |

| Carmit Bachar | American dancer and singer | [85][86] |

| Jürgen Habermas | German philosopher and sociologist | [87] |

| Ljubo Milicevic | Australian professional footballer | [88] |

| Stacy Keach | American actor and narrator | [89] |

| Cheech Marin | American actor and comedian | [90] |

| Owen Schmitt | American football fullback | [91] |

| Tim Lott | English author and journalist | [92] |

| Richard Hawley | English musician | [92] |

| Dario Šarić | Croatian professional basketball player | [93] |

| Antoinette Bourignon | Flemish mystic | [94] |

| Tom Burke | English actor | [95] |

Other animals

Cleft lips and palates are occasionally seen in cattle and dogs, and rarely in goats, sheep, cats, horses, pandas and ferrets. Most commonly, the defect involves the lip, rhinarium, and premaxilla. Clefts of the hard and soft palate are sometimes seen with a cleft lip. The cause is usually hereditary. Brachycephalic dogs such as Boxers and Boston Terriers are most commonly affected.[96] An inherited disorder with incomplete penetrance has also been suggested in Shih tzus, Swiss Sheepdogs, Bulldogs, and Pointers.[97] In horses, it is a rare condition usually involving the caudal soft palate.[98] In Charolais cattle, clefts are seen in combination with arthrogryposis, which is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. It is also inherited as an autosomal recessive trait in Texel sheep. Other contributing factors may include maternal nutritional deficiencies, exposure in utero to viral infections, trauma, drugs, or chemicals, or ingestion of toxins by the mother, such as certain lupines by cattle during the second or third month of gestation.[99] The use of corticosteroids during pregnancy in dogs and the ingestion of Veratrum californicum by pregnant sheep have also been associated with cleft formation.[100]

Difficulty with nursing is the most common problem associated with clefts, but aspiration pneumonia, regurgitation, and malnutrition are often seen with cleft palate and is a common cause of death. Providing nutrition through a feeding tube is often necessary, but corrective surgery in dogs can be done by the age of twelve weeks.[96] For cleft palate, there is a high rate of surgical failure resulting in repeated surgeries.[101] Surgical techniques for cleft palate in dogs include prosthesis, mucosal flaps, and microvascular free flaps.[102] Affected animals should not be bred due to the hereditary nature of this condition.

- Cleft lip in a Boxer

- Cleft lip in a Boxer with premaxillary involvement

- Same dog as picture on left, one year later

See also

- Smile Pinki

- Palatal obturator

- Vomer flap surgery

- Cleft lip and palate organisations

- Face and neck development of the embryo

References

Notes

- "Facts about Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate". October 20, 2014. Archived from the original on 8 May 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- Watkins, SE; Meyer, RE; Strauss, RP; Aylsworth, AS (April 2014). "Classification, epidemiology, and genetics of orofacial clefts". Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 41 (2): 149–63. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2013.12.003. PMID 24607185.

- Roth, Gregory A; Abate, Degu; Abate, Kalkidan Hassen; Abay, Solomon M; Abbafati, Cristiana; Abbasi, Nooshin; Abbastabar, Hedayat; Abd-Allah, Foad; Abdela, Jemal (2018-11-10). "Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017". The Lancet. 392 (10159): 1736–1788. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 6227606. PMID 30496103.

- "GBD Results Tool | GHDx". ghdx.healthdata.org. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- Boklage, Charles E. (2010). How new humans are made cells and embryos, twins and chimeras, left and right, mind/selfsoul, sex, and schizophrenia. Singapore: World Scientific. p. 283. ISBN 9789812835147. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- Kim EK, Khang SK, Lee TJ, Kim TG (May 2010). "Clinical features of the microform cleft lip and the ultrastructural characteristics of the orbicularis oris muscle". Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 47 (3): 297–302. doi:10.1597/08-270.1. PMID 19860522.

- Yuzuriha S, Mulliken JB (November 2008). "Minor-form, microform, and mini-microform cleft lip: anatomical features, operative techniques, and revisions". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 122 (5): 1485–93. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e31818820bc. PMID 18971733.

- Tosun Z, Hoşnuter M, Sentürk S, Savaci N (2003). "Reconstruction of microform cleft lip". Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 37 (4): 232–5. doi:10.1080/02844310310016412. PMID 14582757.

- Tollefson TT, Humphrey CD, Larrabee WF, Adelson RT, Karimi K, Kriet JD (2011). "The spectrum of isolated congenital nasal deformities resembling the cleft lip nasal morphology". Arch Facial Plast Surg. 13 (3): 152–60. doi:10.1001/archfacial.2011.26. PMID 21576661.

- Sloan GM (2000). "Posterior pharyngeal flap and sphincter pharyngoplasty: the state of the art". Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 37 (2): 112–22. doi:10.1597/1545-1569(2000)037<0112:PPFASP>2.3.CO;2. PMID 10749049.

- Hill JS (2001). "Velopharyngeal insufficiency: An update on diagnostic and surgical techniques". Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 9 (6): 365–8. doi:10.1097/00020840-200112000-00005.

- Kaplan EN (1975). "The Occult and Submucous Cleft Palate". Cleft Palate Journal. 12: 356–68. PMID 1058746.

- Hanny, KH (2015). "Late detection of cleft palate". European Journal of Pediatrics. 175 (1): 71–80. doi:10.1007/s00431-015-2590-9. PMC 4709386. PMID 26231683.

- "Cleft Lip and Palate". American-Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- Leonard BJ, Brust JD (1991). "Self-concept of children and adolescents with cleft lip and/or palate". Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 28 (4): 347–353. doi:10.1597/1545-1569(1991)028<0347:SCOCAA>2.3.CO;2. PMID 1742302.

- Tobiasen JM (July 1984). "Psychosocial correlates of congenital facial clefts: a conceptualization and model". Cleft Palate J. 21 (3): 131–9. PMID 6592056.

- Pope AW, Ward J (1997). "Self-perceived facial appearance and psychosocial adjustment in preadolescents with craniofacial anomalies". Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 34 (5): 396–401. doi:10.1597/1545-1569(1997)034<0396:SPFAAP>2.3.CO;2. PMID 9345606.

- Bristow & Bristow 2007, pp. 82–92

- "Cleft Palate Foundation". Archived from the original on 2007-07-01. Retrieved 2007-07-01.

- Snyder HT, Bilboul MJ, Pope AW (2005). "Psychosocial adjustment in adolescents with craniofacial anomalies: a comparison of parent and self-reports". Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 42 (5): 548–55. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.624.1274. doi:10.1597/04-078R.1. PMID 16149838.

- Endriga MC, Kapp-Simon KA (1999). "Psychological issues in craniofacial care: state of the art". Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 36 (1): 3–11. doi:10.1597/1545-1569(1999)036<0001:PIICCS>2.3.CO;2. PMID 10067755.

- Pope AW, Snyder HT (July 2005). "Psychosocial adjustment in children and adolescents with a craniofacial anomaly: age and sex patterns". Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 42 (4): 349–54. doi:10.1597/04-043R.1. PMID 16001914.

- Prokhorov AV, Perry CL, Kelder SH, Klepp KI (1993). "Lifestyle values of adolescents: results from Minnesota Heart Health Youth Program". Adolescence. 28 (111): 637–47. PMID 8237549.

- Roberts, Rachel M.; Mathias, Jane L.; Wheaton, Patricia (2012), "Cognitive Functioning in Children and Adults With Nonsyndromal Cleft Lip and/or Palate: A Meta-analysis", Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 37 (7): 786–797, doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jss052, PMID 22451260

- Dudas M, Li WY, Kim J, Yang A, Kaartinen V (2007). "Palatal fusion — where do the midline cells go? A review on cleft palate, a major human birth defect". Acta Histochem. 109 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.acthis.2006.05.009. PMID 16962647.

- Dudas M, Li WY, Kim J, Yang A, Kaartinen V (2007). "Palatal fusion — where do the midline cells go? A review on cleft palate, a major human birth defect". Acta Histochem. 109 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.acthis.2006.05.009. PMID 16962647.

- Meeks, Naomi J.L.; Saenz, Margarita; Tsai, Anne Chun-Hui; Elias, Ellen R. (2018), Hay, Jr., William W.; Levin, Myron J.; Deterding, Robin R.; Abzug, Mark J. (eds.), "Genetics & Dysmorphology", Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Pediatrics (24 ed.), McGraw-Hill Education, retrieved 2019-08-06

- Beaty TH, Ruczinski I, Murray JC, et al. (May 2011). "Evidence for gene-environment interaction in a genome wide study of isolated, non-syndromic cleft palate". Genet Epidemiol. 35 (6): 469–78. doi:10.1002/gepi.20595. PMC 3180858. PMID 21618603.

- Kanno K, Suzuki Y, Yamada A, Aoki Y, Kure S, Matsubara Y (May 2004). "Association between nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate and the glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 gene in the Japanese population". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 127A (1): 11–6. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.20649. PMID 15103710.

- Sandoiu, Ana (2017-01-17). "Scientists find genetic mutation that causes cleft lip and palate, heart defects". Medical News Today. Archived from the original on 2017-01-29. Retrieved 2017-01-31.

- Dixon MJ, Marazita ML, Beaty TH, Murray JC (March 2011). "Cleft lip and palate: synthesizing genetic and environmental influences". Nature Reviews Genetics. 12 (3): 167–78. doi:10.1038/nrg2933. PMC 3086810. PMID 21331089.

- Zucchero TM, Cooper ME, Maher BS, et al. (August 2004). "Interferon regulatory factor 6 (IRF6) gene variants and the risk of isolated cleft lip or palate". N. Engl. J. Med. 351 (8): 769–80. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa032909. PMID 15317890.

- "Cleft palate genetic clue found". BBC News. 2004-08-30. Archived from the original on 2007-02-08. Retrieved 2007-07-01.

- Siderius LE, Hamel BC, van Bokhoven H, et al. (2000). "X-linked mental retardation associated with cleft lip/palate maps to Xp11.3-q21.3". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 85 (3): 216–220. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19990730)85:3<216::AID-AJMG6>3.0.CO;2-X. PMID 10398231.

- Kronwith SD, Quinn G, McDonald DM, et al. (1990). "Stickler's syndrome in the Cleft Palate Clinic". J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 27 (5): 265–7. PMID 2246742.

- Mrugacz M, Sredzińska-Kita D, Bakunowicz-Lazarczyk A, Piszcz M (2005). "[High myopia as a pathognomonic sign in Stickler's syndrome]". Klin Oczna (in Polish). 107 (4–6): 369–71. PMID 16118961.

- Sousa SB, Lambot-Juhan K, Rio M, et al. (May 2011). "Expanding the skeletal phenotype of Loeys-Dietz syndrome". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 155A (5): 1178–83. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.33813. PMID 21484991.

- Hardikar syndrome symptoms

- Wall, James; Albanese, Craig T. (2015), Doherty, Gerard M. (ed.), "Pediatric Surgery", CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Surgery (14 ed.), McGraw-Hill Education, retrieved 2019-08-06

- Meeks, Naomi J.L.; Saenz, Margarita; Tsai, Anne Chun-Hui; Elias, Ellen R. (2018), Hay, Jr., William W.; Levin, Myron J.; Deterding, Robin R.; Abzug, Mark J. (eds.), "Genetics & Dysmorphology", Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Pediatrics (24 ed.), McGraw-Hill Education, retrieved 2019-08-06

- Cox, T. C. (2004). "Taking it to the max: The genetic and developmental mechanisms coordinating midfacial morphogenesis and dysmorphology". Clin. Genet. 65 (3): 163–176. doi:10.1111/j.0009-9163.2004.00225.x. PMID 14756664.

- Loenarz, C.; Ge W.; Coleman M. L.; Rose N. R.; Cooper C. D. O.; Klose R. J.; Ratcliffe P. J.; Schofield, C. J. (2009). "PHF8, a gene associated with cleft lip/palate and mental retardation, encodes for an N{varepsilon}-dimethyl lysine demethylase". Hum. Mol. Genet. 19 (2): 217–22. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddp480. PMC 4673897. PMID 19843542.

- Millicovsky, G.; Johnston, M.C. (1981). "Hyperoxia and hypoxia in pregnancy: simple experimental manipulation alters the incidence of cleft lip and palate in CL/Fr mice". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78 (9): 5722–5723. Bibcode:1981PNAS...78.5722M. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.9.5722. PMC 348841. PMID 6946511.

- Shi, M.; Wehby, G.L.; Murray, J.C. (2008). "Review on Genetic Variants and Maternal Smoking in the Etiology of Oral Clefts and Other Birth Defects". Birth Defects Res., Part C. 84 (1): 16–29. doi:10.1002/bdrc.20117. PMC 2570345. PMID 18383123.

- Hurst, J. A.; Houlston, R.S.; Roberts, A.; Gould, S.J.; Tingey, W.G. (1995). "Transverse limb deficiency, facial clefting and hypoxic renal damage: an association with treatment of maternal hypertension?". Clin. Dysmorphol. 4 (4): 359–363. doi:10.1097/00019605-199510000-00013. PMID 8574428.

- Boyles AL, Wilcox AJ, Taylor JA, et al. (February 2008). "Folate and One-Carbon Metabolism Gene Polymorphisms and Their Associations With Oral Facial Clefts". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 146A (4): 440–9. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.32162. PMC 2366099. PMID 18203168.

- Costello BJ, Edwards SP, Clemens M (October 2008). "Fetal diagnosis and treatment of craniomaxillofacial anomalies". J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 66 (10): 1985–95. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2008.01.042. PMID 18848093.

- Tessier P (June 1976). "Anatomical classification facial, cranio-facial and latero-facial clefts". J Maxillofac Surg. 4 (2): 69–92. doi:10.1016/S0301-0503(76)80013-6. PMID 820824.

- Allori, AC; Mulliken, JG; Meara, JG (March 2017). "Classification of Cleft Lip/Palate: Then and Now". Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 54 (2): 175–188. doi:10.1597/14-080. PMID 26339868.

- Bristow, L; Bristow, S (2007). Making faces: Logan's cleft lip and palate story. Oakville, Ontaria, CA: Pulsus Group. pp. 1–92.

- Lydiatt DD, Yonkers AJ, Schall DG (November 1989). "The management of the cleft lip and palate patient". Nebr Med J. 74 (11): 325–8, discussion 328–9. PMID 2586685.

- M, Sriram Bhat; M, Sriram Bhat (2014). SRB's Surgical Operations: Text & Atlas. JP Medical Ltd. p. 414. ISBN 9789350251218.

- "Biography and Personal Archive". Archived from the original on 2007-06-17. Retrieved 2007-07-01. at miami.edu

- Barillas I, Dec W, Warren SM, Cutting CB, Grayson BH (March 2009). "Nasoalveolar molding improves long-term nasal symmetry in complete unilateral cleft lip-cleft palate patients". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 123 (3): 1002–6. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e318199f46e. PMID 19319066.

- Fukuyama E, Omura S, Fujita K, Soma K, Torikai K (November 2006). "Excessive rapid palatal expansion with Latham appliance for distal repositioning of protruded premaxilla in bilateral cleft lip and alveolus". Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 43 (6): 673–7. doi:10.1597/05-109. PMID 17105324.

- Lawrence CW, Philips BJ (January 1975). "A telefluoroscopic study of lingual contacts made by persons with palatal defects". Cleft Palate J. 12: 85–94. PMID 1053965.

- Kummer AW. (2020). Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Conditions: A Comprehensive Guide to Clinical Management, 4th Edition. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Chapman KL (January 1993). "Phonologic processes in children with cleft palate". Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 30 (1): 64–72. doi:10.1597/1545-1569(1993)030<0064:PPICWC>2.3.CO;2. PMID 8418874.

- Trost JE (July 1981). "Articulatory additions to the classical description of the speech of persons with cleft palate". Cleft Palate J. 18 (3): 193–203. PMID 6941865.

- Kummer AW. (2020). Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Conditions: A Comprehensive Guide to Clinical Management, 4th Edition. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Szabo C, Langevin K, Schoem S, Mabry K (August 2010). "Treatment of persistent middle ear effusion in cleft palate patients". Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 74 (8): 874–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.04.016. PMID 20537733.

- Cohen MS, Mandel EM, Furman JM, Sparto PJ, Casselbrant ML (June 2011). "Tympanostomy Tube Placement and Vestibular Function in Children". Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 145 (4): 666–72. doi:10.1177/0194599811412038. PMC 3856627. PMID 21676943.

- Broen, PA; Moller, KT; Carlstrom, J; Doyle, SS; Devers, M; Keenan, KM (March 1996). "Comparison of the hearing histories of children with and without cleft palate". The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 33 (2): 127–33. doi:10.1597/1545-1569(1996)033<0127:COTHHO>2.3.CO;2. PMID 8695620.

- Scalzone A, Flores-Mir C, Carozza D, d'Apuzzo F, Grassia V, Perillo L (2019). "Secondary alveolar bone grafting using autologous versus alloplastic material in the treatment of cleft lip and palate patients: systematic review and meta-analysis". Prog Orthod. 20 (1): 6. doi:10.1186/s40510-018-0252-y. PMC 6369233. PMID 30740615.

- Roy AA, Rtshiladze MA, Stevens K, Phillips J (2019). "Orthognathic Surgery for Patients with Cleft Lip and Palate". Clin Plast Surg. 46 (2): 157–171. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2018.11.002. PMID 30851748.

- Joanne Green. "The Importance of a Multi-Disciplinary Approach". Archived from the original on 2007-10-26. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- Sitzman, TJ; Allori, AC; Thorburn, G (April 2014). "Measuring outcomes in cleft lip and palate treatment". Clinics of Plastic Surgery. 41 (2): 311–9. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2013.12.001. PMID 24607197.

- "ICHOM | Cleft Lip & Palate Standard Set | Measuring Outcomes".

- Allori, AC; Kelley, T; Meara, JG (September 2017). "A standard set of outcome measures for the comprehensive appraisal of cleft care". Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 54 (5): 540–554. doi:10.1597/15-292. PMID 27223626.

- "WHO | International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)".

- "Prevalence of Cleft Lip & Cleft Palate | National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research". www.nidcr.nih.gov. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- See "Who is affected by cleft lip and cleft palate". Archived from the original on 2008-03-30. Retrieved 2008-06-20.

- Cervenka J, Shapiro BL (February 1970). "Cleft uvula in Chippewa Indians: prevalence and genetics". Hum. Biol. 42 (1): 47–52. PMID 5445084.

- Rivron RP (March 1989). "Bifid uvula: prevalence and association in otitis media with effusion in children admitted for routine otolaryngological operations". J Laryngol Otol. 103 (3): 249–52. doi:10.1017/S002221510010862X. PMID 2784825.

- Paolini, Christopher (November 8, 2011). "Chapter 9: Rudely Into the Light, Chapter 10: A Cradle Song". Inheritance. Knopf Books for Young Readers. pp. 69–78. ISBN 978-0375856112.

- Solomon, Jon (2001). The ancient world in the cinema (Rev. and expanded ed.). New Haven [u.a.]: Yale Univ. Press. p. 90. ISBN 9780300083378.

- Timothy D. Harfield. "The Monster Without: Red Dragon, the Cleft-Lip, and the Politics of Recognition" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- Plante, Chris (June 14, 2018). "When I asked about Rage 2's worst character, I got an unexpected response". Polygon. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- Plante, Chris (May 13, 2019). "Rage 2 is a fun game that makes me feel like garbage". Polygon. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- Nico Van Thyn (June 8, 2012). "Once a Knight: The legendary man, Mr. Byrd". nvanthyn.blogsport.com. Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- Karen Holliday Tanner (1998). Doc Holliday: A Family Portrait. University of Omaha Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3036-1.

- "King Tut Not Murdered Violently, CT Scans Show". Archived from the original on 2007-07-03. Retrieved 2007-07-01.

- Bloodfeud: Murder and Revenge in Anglo-Saxon England, Richard Fletcher

- "Tad Lincoln: The Not-so-Famous Son of A Most-Famous President". HistoryBuff.com. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-07-01.

- "Carmit Bachar, smile ambassador". Archived from the original on 2007-10-30. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- Beverley Lyons, October 16, 2006. Carmite Doing Her Bit For Charity Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine. The Daily Record

- "Jurgen Habermas". Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- "Chat To Ljubo...LIVE". 28 May 2009. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- "Stacy Keach". Cleft Palate Foundation. Archived from the original on 2007-02-13. Retrieved 2007-07-01.

- "Cheech Marin". Cleft Palate Foundation. Retrieved 2007-07-01.

- Whiteside, Kelly (4 Nov 2006). "Schmitt is face of West Va. toughness| USA Today". Archived from the original on 2009-10-15. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- "Famous People with a Cleft". 2008-04-05. Archived from the original on 2013-01-21.

- "Who's That Guy? Dario Saric!". 2014-09-03. Archived from the original on 2014-08-22.

- MacEwen, Alex (1910). Antoinette Bourignon, Quietist. London: Hodder and Stoughton. p. 27. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- Cartwright, Gemma (30 September 2017). "He Was Born With a Cleft Lip". POPSUGAR Celebrity UK. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- Ettinger, Stephen J.; Feldman, Edward C. (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 978-0-7216-6795-9.

- Garcia, J.F. Rodriguez (2006). "Surgery of the Soft and Hard Palate". Proceedings of the North American Veterinary Conference. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- Semevolos, Stacy A.; Ducharme, Norm (1998). "Surgical Repair of Congenital Cleft Palate in Horses: Eight Cases (1979–1997)" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Association of Equine Practitioners. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- "Mouth". The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- Beasley, V. (1999). "Teratogenic Agents". Veterinary Toxicology. Archived from the original on 2004-09-20. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- Lee J, Kim Y, Kim M, Lee J, Choi J, Yeom D, Park J, Hong S (2006). "Application of a temporary palatal prosthesis in a puppy suffering from cleft palate". J. Vet. Sci. 7 (1): 93–5. doi:10.4142/jvs.2006.7.1.93. PMC 3242096. PMID 16434860.

- Griffiths L, Sullivan M (2001). "Bilateral overlapping mucosal single-pedicle flaps for correction of soft palate defects". Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association. 37 (2): 183–6. doi:10.5326/15473317-37-2-183. PMID 11300527.

Further reading

- FIGURE 1 | Development of the lip and palate and FIGURE 2 | Types of cleft in Dixon, Michael J.; Marazita, Mary L.; Beaty, Terri H.; Murray, Jeffrey C. (2011). "Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences". Nature Reviews Genetics. 12 (3): 167–178. doi:10.1038/nrg2933. PMC 3086810. PMID 21331089.

- Berkowitz, Samuel (26 February 2013). Cleft Lip and Palate: Diagnosis and Management. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-30770-6.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Look up cleft lip in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cleft lip. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Cleft Palate. |

- Cleft lip and cleft palate at Curlie