Sinusitis

Sinusitis, also known as rhinosinusitis, is inflammation of the mucous membranes that line the sinuses resulting in symptoms.[1][7] Common symptoms include thick nasal mucus, a plugged nose, and facial pain.[1][7] Other signs and symptoms may include fever, headaches, a poor sense of smell, sore throat, and a cough.[2][3] The cough is often worse at night.[3] Serious complications are rare.[3] It is defined as acute sinusitis if it lasts fewer than 4 weeks, and as chronic sinusitis if it lasts for more than 12 weeks.[1]

| Sinusitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Sinus infection, rhinosinusitis |

| |

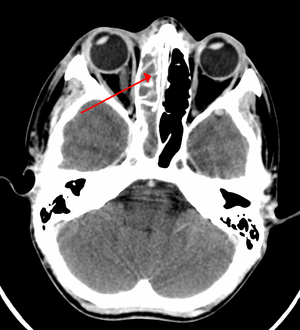

| A CT scan showing sinusitis of the ethmoid sinus | |

| Specialty | Otorhinolaryngology |

| Symptoms | Thick nasal mucus, plugged nose, pain in the face, fever[1][2][3] |

| Causes | Infection (bacterial, fungal, viral), allergies, air pollution, structural problems in the nose[2] |

| Risk factors | Asthma, cystic fibrosis, poor immune function[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Usually based on symptoms[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Migraine[4] |

| Prevention | Handwashing, avoiding smoking, immunization[2] |

| Treatment | Pain medications, nasal steroids, nasal irrigation, antibiotic[1][5] |

| Frequency | 10–30% each year (developed world)[1][6] |

Sinusitis can be caused by infection, allergies, air pollution, or structural problems in the nose.[2] Most cases are caused by a viral infection.[2] A bacterial infection may be present if symptoms last more than 10 days or if a person worsens after starting to improve.[1] Recurrent episodes are more likely in persons with asthma, cystic fibrosis, and poor immune function.[1] X-rays are not usually needed unless complications are suspected.[1] In chronic cases, confirmatory testing is recommended by either direct visualization or computed tomography.[1]

Some cases may be prevented by hand washing, avoiding smoking, and immunization.[2] Pain killers such as naproxen, nasal steroids, and nasal irrigation may be used to help with symptoms.[1][5] Recommended initial treatment for acute sinusitis is watchful waiting.[1] If symptoms do not improve in 7–10 days or get worse, then an antibiotic may be used or changed.[1] In those in whom antibiotics are used, either amoxicillin or amoxicillin/clavulanate is recommended first line.[1] Surgery may occasionally be used in people with chronic disease.[8]

Sinusitis is a common condition.[1] It affects between about 10 and 30 percent of people each year in the United States and Europe.[1][6] Women are more often affected than men.[9] Chronic sinusitis affects about 12.5% of people.[10] Treatment of sinusitis in the United States results in more than US$11 billion in costs.[1] The unnecessary and ineffective treatment of viral sinusitis with antibiotics is common.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Headache or facial pain or pressure of a dull, constant, or aching sort over the affected sinuses is common with both acute and chronic stages of sinusitis. This pain is usually localized to the involved sinus and may worsen when the affected person bends over or when lying down. Pain often starts on one side of the head and progresses to both sides.[11] Acute sinusitis may be accompanied by thick nasal discharge that is usually green in color and may contain pus or blood.[12] Often, a localized headache or toothache is present, and these symptoms distinguish a sinus-related headache from other types of headaches, such as tension and migraine headaches. Another way to distinguish between toothache and sinusitis is that the pain in sinusitis is usually worsened by tilting the head forwards and with valsalva maneuvers.[13]

Infection of the eye socket is possible, which may result in the loss of sight and is accompanied by fever and severe illness. Another possible complication is the infection of the bones (osteomyelitis) of the forehead and other facial bones – Pott's puffy tumor.[11]

Sinus infections can also cause middle-ear problems due to the congestion of the nasal passages. This can be demonstrated by dizziness, "a pressurized or heavy head", or vibrating sensations in the head. Postnasal drip is also a symptom of chronic rhinosinusitis.

Halitosis (bad breath) is often stated to be a symptom of chronic rhinosinusitis; however, gold-standard breath analysis techniques have not been applied. Theoretically, several possible mechanisms of both objective and subjective halitosis may be involved.[13]

A 2004 study suggested that up to 90% of "sinus headaches" are actually migraines.[14][15] The confusion occurs in part because migraine involves activation of the trigeminal nerves, which innervate both the sinus region and the meninges surrounding the brain. As a result, accurately determining the site from which the pain originates is difficult. People with migraines do not typically have the thick nasal discharge that is a common symptom of a sinus infection.[16]

By location

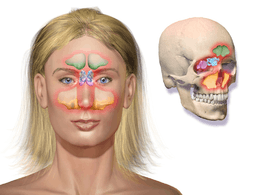

The four paired paranasal sinuses are the frontal, ethmoidal, maxillary, and sphenoidal sinuses. The ethmoidal sinuses are further subdivided into anterior and posterior ethmoid sinuses, the division of which is defined as the basal lamella of the middle nasal concha. In addition to the severity of disease, discussed below, sinusitis can be classified by the sinus cavity it affects:

- Maxillary – can cause pain or pressure in the maxillary (cheek) area (e.g., toothache,[13] or headache) (J01.0/J32.0)

- Frontal – can cause pain or pressure in the frontal sinus cavity (located above the eyes), headache, particularly in the forehead (J01.1/J32.1)

- Ethmoidal – can cause pain or pressure pain between/behind the eyes, the sides of the upper part of the nose (the medial canthi), and headaches (J01.2/J32.2)[17]

- Sphenoidal – can cause pain or pressure behind the eyes, but is often felt in the top of the head, over the mastoid processes, or the back of the head.[17]

Complications

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Preseptal cellulitis |

| II | Orbital cellulitis |

| III | Subperiosteal abscess |

| IV | Orbital abscess |

| V | Cavernous sinus septic thrombosis |

The proximity of the brain to the sinuses makes the most dangerous complication of sinusitis, particularly involving the frontal and sphenoid sinuses, infection of the brain by the invasion of anaerobic bacteria through the bones or blood vessels. Abscesses, meningitis, and other life-threatening conditions may result. In extreme cases, the patient may experience mild personality changes, headache, altered consciousness, visual problems, seizures, coma, and possibly death.[11]

Sinus infection can spread through anastomosing veins or by direct extension to close structures. Orbital complications were categorized by Chandler et al. into five stages according to their severity (see table).[18] Contiguous spread to the orbit may result in periorbital cellulitis, subperiosteal abscess, orbital cellulitis, and abscess. Orbital cellulitis can complicate acute ethmoiditis if anterior and posterior ethmoidal veins thrombophlebitis enables the spread of the infection to the lateral or orbital side of the ethmoid labyrinth. Sinusitis may extend to the central nervous system, where it may cause cavernous sinus thrombosis, retrograde meningitis, and epidural, subdural, and brain abscesses.[19] Orbital symptoms frequently precede intracranial spread of the infection . Other complications include sinobronchitis, maxillary osteomyelitis, and frontal bone osteomyelitis.[20][21][22][23] Osteomyelitis of the frontal bone often originates from a spreading thrombophlebitis. A periostitis of the frontal sinus causes an osteitis and a periostitis of the outer membrane, which produces a tender, puffy swelling of the forehead.

The diagnosis of these complications can be assisted by noting local tenderness and dull pain, and can be confirmed by CT and nuclear isotope scanning. The most common microbial causes are anaerobic bacteria and S. aureus. Treatment includes performing surgical drainage and administration of antimicrobial therapy. Surgical debridement is rarely required after an extended course of parenteral antimicrobial therapy.[24] Antibiotics should be administered for at least 6 weeks. Continuous monitoring of people for possible intracranial complication is advised.

Causes

Maxillary sinusitis may also develop from problems with the teeth, and these cases make up between 10 and 40% of cases.[25] The cause of this situation is usually a periapical or periodontal infection of a maxillary posterior tooth, where the inflammatory exudate has eroded through the bone superiorly to drain into the maxillary sinus. Once an odontogenic infection involves the maxillary sinus, it may then spread to the orbit or to the ethmoid sinus, the nasal cavity, and frontal sinuses, and in unusual instances can spread from the maxillary sinus causing orbital cellulitis, blindness, meningitis, subdural empyema, brain abscess and life-threatening cavernous sinus thrombosis.[26][27] Limited field CBCT imaging, as compared to periapical radiographs, improves the ability to detect the teeth as the sources for sinusitis.[27] Treatment focuses on removing the infection and preventing reinfection, by removing of the microorganisms, their byproducts, and pulpal debris from the infected root canal.[27] Systemic antibiotics is ineffective as a definitive solution, but may afford temporary relief of symptoms by improving sinus clearing, and may be appropriate for rapidly spreading infections, but debridement and disinfection of the root canal system at the same time is necessary.[27]

Chronic sinusitis can also be caused indirectly through a common but slight abnormality in the auditory or eustachian tube, which is connected to the sinus cavities and the throat. Other diseases such as cystic fibrosis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis can also cause chronic sinusitis. This tube is usually almost level with the eye sockets, but when this sometimes hereditary abnormality is present, it is below this level and sometimes level with the vestibule or nasal entrance.

Acute

Acute sinusitis is usually precipitated by an earlier upper respiratory tract infection, generally of viral origin, mostly caused by rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, and influenza viruses, others caused by adenoviruses, human parainfluenza viruses, human respiratory syncytial virus, enteroviruses other than rhinoviruses, and metapneumovirus. If the infection is of bacterial origin, the most common three causative agents are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis.[28] Until recently, H. influenzae was the most common bacterial agent to cause sinus infections. However, introduction of the H. influenzae type B (Hib) vaccine has dramatically decreased these infections and now non-typable H. influenzae (NTHI) is predominantly seen in clinics. Other sinusitis-causing bacterial pathogens include S. aureus and other streptococci species, anaerobic bacteria and, less commonly, Gram-negative bacteria. Viral sinusitis typically lasts for 7 to 10 days,[28] whereas bacterial sinusitis is more persistent. Around 0.5 to 2.0% of viral sinusitis results in subsequent bacterial sinusitis.

Acute episodes of sinusitis can also result from fungal invasion. These infections are typically seen in people with diabetes or other immune deficiencies (such as AIDS or transplant on immunosuppressive antirejection medications) and can be life-threatening. In type I diabetics, ketoacidosis can be associated with sinusitis due to mucormycosis.[29]

Chemical irritation can also trigger sinusitis, commonly from cigarette smoke and chlorine fumes.[30] It may also be caused by a tooth infection.[28]

Chronic

By definition, chronic sinusitis lasts longer than 12 weeks and can be caused by many different diseases that share chronic inflammation of the sinuses as a common symptom. Symptoms may include any combination of: nasal congestion, facial pain, headache, night-time coughing, an increase in previously minor or controlled asthma symptoms, general malaise, thick green or yellow discharge, feeling of facial fullness or tightness that may worsen when bending over, dizziness, aching teeth, and/or bad breath.[31] Each of these symptoms has multiple other possible causes, which should be considered and investigated, as well. Often, chronic sinusitis can lead to anosmia, the inability to smell objects.[31] In a small number of cases, acute or chronic maxillary sinusitis is associated with a dental infection. Vertigo, lightheadedness, and blurred vision are not typical in chronic sinusitis and other causes should be investigated.

Chronic sinusitis cases are subdivided into cases with and without polyps. When polyps are present, the condition is called chronic hyperplastic sinusitis; however, the causes are poorly understood[28] and may include allergy, environmental factors such as dust or pollution, bacterial infection, or fungi (either allergic, infective, or reactive).

Chronic rhinosinusitis represents a multifactorial inflammatory disorder, rather than simply a persistent bacterial infection.[28] The medical management of chronic rhinosinusitis is now focused upon controlling the inflammation that predisposes people to obstruction, reducing the incidence of infections. However, all forms of chronic rhinosinusitis are associated with impaired sinus drainage and secondary bacterial infections. Most individuals require initial antibiotics to clear any infection and intermittently afterwards to treat acute exacerbations of chronic rhinosinusitis.

A combination of anaerobic and aerobic bacteria is detected in conjunction with chronic sinusitis. Also isolated are S. aureus, including methicillin-resistant S. aureus, and coagulase-negative staphylococci and Gram-negative enteric bacteria can be isolated.

Attempts have been made to provide a more consistent nomenclature for subtypes of chronic sinusitis. The presence of eosinophils in the mucous lining of the nose and paranasal sinuses has been demonstrated for many people, and this has been termed eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis (EMRS). Cases of EMRS may be related to an allergic response, but allergy is not often documented, resulting in further subcategorization into allergic and nonallergic EMRS.[32]

A more recent, and still debated, development in chronic sinusitis is the role that fungi play in this disease.[33] Whether fungi are a definite factor in the development of chronic sinusitis remains unclear, and if they are, what is the difference between those who develop the disease and those who remain free of symptoms. Trials of antifungal treatments have had mixed results.

Recent theories of sinusitis indicate that it often occurs as part of a spectrum of diseases that affect the respiratory tract (i.e., the "one airway" theory) and is often linked to asthma.[34][35] All forms of sinusitis may either result in, or be a part of, a generalized inflammation of the airway, so other airway symptoms, such as cough, may be associated with it.

Both smoking and secondhand smoke are associated with chronic rhinosinusitis.[10]

Pathophysiology

Biofilm bacterial infections may account for many cases of antibiotic-refractory chronic sinusitis.[36][37][38] Biofilms are complex aggregates of extracellular matrix and interdependent microorganisms from multiple species, many of which may be difficult or impossible to isolate using standard clinical laboratory techniques.[39] Bacteria found in biofilms have their antibiotic resistance increased up to 1000 times when compared to free-living bacteria of the same species. A recent study found that biofilms were present on the mucosa of 75% of people undergoing surgery for chronic sinusitis.[40]

Diagnosis

Classification

Sinusitis (or rhinosinusitis) is defined as an inflammation of the mucous membrane that lines the paranasal sinuses and is classified chronologically into several categories:[31]

- Acute sinusitis – A new infection that may last up to four weeks and can be subdivided symptomatically into severe and nonsevere. Some use definitions up to 12 weeks.[1]

- Recurrent acute sinusitis – Four or more full episodes of acute sinusitis that occur within one year

- Subacute sinusitis – An infection that lasts between four and 12 weeks, and represents a transition between acute and chronic infection

- Chronic sinusitis – When the signs and symptoms last for more than 12 weeks.[1]

- Acute exacerbation of chronic sinusitis – When the signs and symptoms of chronic sinusitis exacerbate, but return to baseline after treatment

Roughly 90% of adults have had sinusitis at some point in their lives.[41]

Acute

Health care providers distinguish bacterial and viral sinusitis by watchful waiting.[1] If a person has had sinusitis for fewer than 10 days without the symptoms becoming worse, then the infection is presumed to be viral.[1] When symptoms last more than 10 days or get worse in that time, then the infection is considered bacterial sinusitis.[42] Pain in the teeth and bad breath are also more indicative of bacterial disease.[43]

Imaging by either X-ray, CT or MRI is generally not recommended unless complications develop.[42] Pain caused by sinusitis is sometimes confused for pain caused by pulpitis (toothache) of the maxillary teeth, and vice versa. Classically, the increased pain when tilting the head forwards separates sinusitis from pulpitis.

Chronic

For sinusitis lasting more than 12 weeks, a CT scan is recommended.[42] On a CT scan, acute sinus secretions have a radiodensity of 10 to 25 Hounsfield units (HU), but in a more chronic state they become more viscous, with a radiodensity of 30 to 60 HU.[44]

Nasal endoscopy and clinical symptoms are also used to make a positive diagnosis.[28] A tissue sample for histology and cultures can also be collected and tested.[45] Allergic fungal sinusitis (AFS) is often seen in people with asthma and nasal polyps. In rare cases, sinusoscopy may be made.

Nasal endoscopy involves inserting a flexible fiber-optic tube with a light and camera at its tip into the nose to examine the nasal passages and sinuses.

.jpg) CT of chronic sinusitis

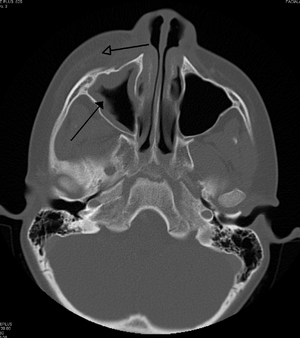

CT of chronic sinusitis CT scan of chronic sinusitis, showing a filled right maxillary sinus with sclerotic thickened bone.

CT scan of chronic sinusitis, showing a filled right maxillary sinus with sclerotic thickened bone. MRI image showing sinusitis. Edema and mucosal thickening appears in both maxillary sinuses.

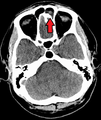

MRI image showing sinusitis. Edema and mucosal thickening appears in both maxillary sinuses. Maxillary sinusitis caused by a dental infection associated with periorbital cellulitis

Maxillary sinusitis caused by a dental infection associated with periorbital cellulitis Frontal sinusitis

Frontal sinusitis X-ray of left-sided maxillary sinusitis marked by an arrow. There is lack of the air transparency indicating fluid in contrast to the other side.

X-ray of left-sided maxillary sinusitis marked by an arrow. There is lack of the air transparency indicating fluid in contrast to the other side.

Treatment

| Treatments[46][47] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Indication | Rationale |

| Time | Viral and some bacterial sinusitis | Sinusitis is usually caused by a virus which is not affected by antibiotics.[46] |

| Antibiotics | Bacterial sinusitis | Cases accompanied by extreme pain, skin infection, or which last a long time may be caused by bacteria.[46] |

| Nasal irrigation | Nasal congestion | Can provide relief by helping decongest.[46] |

| Drink liquids | Thick phlegm | Remaining hydrated loosens mucus.[46] |

| Antihistamines | Concern with allergies | Antihistamines do not relieve typical sinusitis or cold symptoms much; this treatment is not needed in most cases.[46] |

| Nasal spray | Desire for temporary relief | Tentative evidence that it helps symptoms.[5] Does not treat cause. Not recommended for more than three days' use.[46] |

Recommended treatments for most cases of sinusitis include rest and drinking enough water to thin the mucus.[48] Antibiotics are not recommended for most cases.[48][49]

Breathing low-temperature steam such as from a hot shower or gargling can relieve symptoms.[48][50] There is tentative evidence for nasal irrigation in acute sinusitis, for example during upper respiratory infections.[5] Decongestant nasal sprays containing oxymetazoline may provide relief, but these medications should not be used for more than the recommended period. Longer use may cause rebound sinusitis.[51] It is unclear if nasal irrigation, antihistamines, or decongestants work in children with acute sinusitis.[52] There is no clear evidence that plant extracts such as cyclamen europaeum are effective as an intranasal wash to treat acute sinusitis.[53] Evidence is inconclusive on whether anti-fungal treatments improve symptoms or quality of life.[54]

Antibiotics

Most sinusitis cases are caused by viruses and resolve without antibiotics.[28] However, if symptoms do not resolve within 10 days, amoxicillin is a reasonable antibiotic for first treatment,[28] with amoxicillin/clavulanate being indicated if symptoms do not improve after 7 days on amoxicillin alone.[42] A 2012 Cochrane review, however, found only a small benefit between 7 and 14 days, and could not recommend the practice when compared to potential complications and risk of developing resistance.[55] Antibiotics are specifically not recommended in those with mild / moderate disease during the first week of infection due to risk of adverse effects, antibiotic resistance, and cost.[56]

Fluoroquinolones, and a newer macrolide antibiotic such as clarithromycin or a tetracycline like doxycycline, are used in those who have severe allergies to penicillins.[57] Because of increasing resistance to amoxicillin the 2012 guideline of the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends amoxicillin-clavulanate as the initial treatment of choice for bacterial sinusitis.[58] The guidelines also recommend against other commonly used antibiotics, including azithromycin, clarithromycin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, because of growing antibiotic resistance. The FDA recommends against the use of fluoroquinolones when other options are available due to higher risks of serious side effects.[59]

A short-course (3–7 days) of antibiotics seems to be just as effective as the typical longer-course (10–14 days) of antibiotics for those with clinically diagnosed acute bacterial sinusitis without any other severe disease or complicating factors.[60] The IDSA guideline suggest five to seven days of antibiotics is long enough to treat a bacterial infection without encouraging resistance. The guidelines still recommend children receive antibiotic treatment for ten days to two weeks.[58]

Corticosteroids

For unconfirmed acute sinusitis, nasal sprays using corticosteroids have not been found to be better than a placebo either alone or in combination with antibiotics.[61] For cases confirmed by radiology or nasal endoscopy, treatment with intranasal corticosteroids alone or in combination with antibiotics is supported.[62] The benefit, however, is small.[63]

For confirmed chronic rhinosinusitis, there is limited evidence that intranasal steroids improve symptoms and insufficient evidence that one type of steroid is more effective.[64][65]

There is only limited evidence to support short treatment with corticosteroids by mouth for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps.[66][67][68] There is limited evidence to support corticosteroids by mouth in combination with antibiotics for acute sinusitis; it has only short-term effect improving the symptoms.[69][70]

Surgery

For chronic or recurring sinusitis, referral to an otolaryngologist may be indicated, and treatment options may include nasal surgery. Surgery should only be considered for those people who do not benefit with medication.[67][71] It is unclear how benefits of surgery compare to medical treatments in those with nasal polyps as this has been poorly studied.[72][73]

Maxillary antral washout involves puncturing the sinus and flushing with saline to clear the mucus. A 1996 study of people with chronic sinusitis found that washout confers no additional benefits over antibiotics alone.[74]

A number of surgical approaches can be used to access the sinuses and these have generally shifted from external/extranasal approaches to intranasal endoscopic ones. The benefit of functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) is its ability to allow for a more targeted approach to the affected sinuses, reducing tissue disruption, and minimizing post-operative complications.[75] The use of drug eluting stents such as propel mometasone furoate implant may help in recovery after surgery.[76]

Another recently developed treatment is balloon sinuplasty. This method, similar to balloon angioplasty used to "unclog" arteries of the heart, utilizes balloons in an attempt to expand the openings of the sinuses in a less invasive manner.

For persistent symptoms and disease in people who have failed medical and the functional endoscopic approaches, older techniques can be used to address the inflammation of the maxillary sinus, such as the Caldwell-luc antrostomy. This surgery involves an incision in the upper gum, opening in the anterior wall of the antrum, removal of the entire diseased maxillary sinus mucosa and drainage is allowed into inferior or middle meatus by creating a large window in the lateral nasal wall.[77]

Epidemiology

Sinusitis is a common condition, with between 24 and 31 million cases occurring in the United States annually.[78][79] Chronic sinusitis affects approximately 12.5% of people.[10]

Research

Based on recent theories on the role that fungus may play in the development of chronic sinusitis, antifungal treatments have been used, on a trial basis. These trials have had mixed results.[28]

See also

References

- Rosenfeld RM, Piccirillo JF, Chandrasekhar SS, Brook I, Kumar KA, Kramper M, Orlandi RR, Palmer JN, Patel ZM, Peters A, Walsh SA, Corrigan MD (April 2015). "Clinical practice guideline (update): Adult Sinusitis Executive Summary". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 152 (4): 598–609. doi:10.1177/0194599815574247. PMID 25833927.

- "Sinus Infection (Sinusitis)". cdc.gov. September 30, 2013. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "What Are the Symptoms of Sinusitis?". April 3, 2012. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Migraines vs. Sinus Headaches". American Migraine Foundation. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- King D, Mitchell B, Williams CP, Spurling GK (April 2015). "Saline nasal irrigation for acute upper respiratory tract infections" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (4): CD006821. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006821.pub3. PMID 25892369.

- Adkinson, N. Franklin (2014). Middleton's allergy: principles and practice (Eight ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. p. 687. ISBN 9780323085939. Archived from the original on 2016-06-03.

- Head K, Chong LY, Piromchai P, Hopkins C, Philpott C, Schilder AG, Burton MJ (April 2016). "Systemic and topical antibiotics for chronic rhinosinusitis" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD011994. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011994.pub2. PMID 27113482.

- "How Is Sinusitis Treated?". April 3, 2012. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Sinusitis". U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. April 3, 2012. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Hamilos DL (October 2011). "Chronic rhinosinusitis: epidemiology and medical management". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 128 (4): 693–707, quiz 708–9. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.004. PMID 21890184.

- "Sinusitus Complications". Patient Education. University of Maryland. Archived from the original on 2010-02-22.

- "Sinusitis". herb2000.com. Archived from the original on 2011-05-25.

Incidence of acute sinusitis almost always set in following the appearance of a cold for several days at a stretch in the person to the point that all the profuse nasal discharge turns a distinct yellow or a dark green color, or perhaps very thick, and foul-smelling in some cases.

- Ferguson M (September 2014). "Rhinosinusitis in oral medicine and dentistry". Australian Dental Journal. 59 (3): 289–95. doi:10.1111/adj.12193. PMID 24861778.

- Schreiber CP, Hutchinson S, Webster CJ, Ames M, Richardson MS, Powers C (September 2004). "Prevalence of migraine in patients with a history of self-reported or physician-diagnosed "sinus" headache". Archives of Internal Medicine. 164 (16): 1769–72. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.16.1769. PMID 15364670.

- Mehle ME, Schreiber CP (October 2005). "Sinus headache, migraine, and the otolaryngologist". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 133 (4): 489–96. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2005.05.659. PMID 16213917.

- Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society (2004). "The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition". Cephalalgia. 24 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1): 9–160. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00653.x. PMID 14979299.

- Terézhalmy GT, Huber MA, Jones AC; Noujeim M; Sankar V (2009). Physical evaluation in dental practice. Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8138-2131-3.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Chandler JR, Langenbrunner DJ, Stevens ER (September 1970). "The pathogenesis of orbital complications in acute sinusitis". The Laryngoscope. 80 (9): 1414–28. doi:10.1288/00005537-197009000-00007. PMID 5470225.

- Baker AS (September 1991). "Role of anaerobic bacteria in sinusitis and its complications". The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. Supplement. 154 (9_suppl): 17–22. doi:10.1177/00034894911000s907. PMID 1952679.

- Clayman GL, Adams GL, Paugh DR, Koopmann CF (March 1991). "Intracranial complications of paranasal sinusitis: a combined institutional review". The Laryngoscope. 101 (3): 234–9. doi:10.1288/00005537-199103000-00003. PMID 2000009.

- Arjmand EM, Lusk RP, Muntz HR (November 1993). "Pediatric sinusitis and subperiosteal orbital abscess formation: diagnosis and treatment". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 109 (5): 886–94. doi:10.1177/019459989310900518. PMID 8247570.

- Harris GJ (March 1994). "Subperiosteal abscess of the orbit. Age as a factor in the bacteriology and response to treatment". Ophthalmology. 101 (3): 585–95. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(94)31297-8. PMID 8127580.

- Dill SR, Cobbs CG, McDonald CK (February 1995). "Subdural empyema: analysis of 32 cases and review". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 20 (2): 372–86. doi:10.1093/clinids/20.2.372. PMID 7742444.

- Stankiewicz JA, Newell DJ, Park AH (August 1993). "Complications of inflammatory diseases of the sinuses". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 26 (4): 639–55. PMID 7692375.

- Workman AD, Granquist EJ, Adappa ND (February 2018). "Odontogenic sinusitis: developments in diagnosis, microbiology, and treatment". Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 26 (1): 27–33. doi:10.1097/MOO.0000000000000430. PMID 29084007.

- Hupp JR, Ellis E, Tucker MR (2008). Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery (5th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby Elsevier. pp. 317–333. ISBN 9780323049030.

- "Maxillary Sinusitis of Endodontic Origin" (PDF). American Association of Endodontists. 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- Leung RS, Katial R (March 2008). "The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic sinusitis". Primary Care. 35 (1): 11–24, v–vi. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2007.09.002. PMID 18206715.

- Mucormycosis at eMedicine

- Gelfand, Jonathan L. "Help for Sinus Pain and Pressure". WebMD.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- Christine Radojicic. "Sinusitis". Disease Management Project. Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- Chakrabarti A, Denning DW, Ferguson BJ, Ponikau J, Buzina W, Kita H, Marple B, Panda N, Vlaminck S, Kauffmann-Lacroix C, Das A, Singh P, Taj-Aldeen SJ, Kantarcioglu AS, Handa KK, Gupta A, Thungabathra M, Shivaprakash MR, Bal A, Fothergill A, Radotra BD (September 2009). "Fungal rhinosinusitis: a categorization and definitional schema addressing current controversies". The Laryngoscope. 119 (9): 1809–18. doi:10.1002/lary.20520. PMC 2741302. PMID 19544383.

- S; Boodman, ra G. (1999-11-23). "Mayo Report on Sinusitis Draws Skeptics". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2018-06-01.

- Grossman J (February 1997). "One airway, one disease". Chest. 111 (2 Suppl): 11S–16S. doi:10.1378/chest.111.2_Supplement.11S. PMID 9042022.

- Cruz AA (July 2005). "The 'united airways' require an holistic approach to management". Allergy. 60 (7): 871–4. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00858.x. PMID 15932375.

- Palmer JN (December 2005). "Bacterial biofilms: do they play a role in chronic sinusitis?". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 38 (6): 1193–201, viii. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2005.07.004. PMID 16326178.

- Ramadan HH, Sanclement JA, Thomas JG (March 2005). "Chronic rhinosinusitis and biofilms". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 132 (3): 414–7. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2004.11.011. PMID 15746854.

- Bendouah Z, Barbeau J, Hamad WA, Desrosiers M (June 2006). "Biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa is associated with an unfavorable evolution after surgery for chronic sinusitis and nasal polyposis". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 134 (6): 991–6. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2006.03.001. PMID 16730544.

- Lewis, Kim; Salyers, Abagail A.; Taber, Harry W.; Wax, Richard G., eds. (2002). Bacterial Resistance to Antimicrobials. New York: Marcel Decker. ISBN 978-0-8247-0635-7. Archived from the original on 2014-01-07.

- Sanclement JA, Webster P, Thomas J, Ramadan HH (April 2005). "Bacterial biofilms in surgical specimens of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis". The Laryngoscope. 115 (4): 578–82. doi:10.1097/01.mlg.0000161346.30752.18. PMID 15805862.

- Pearlman AN, Conley DB (June 2008). "Review of current guidelines related to the diagnosis and treatment of rhinosinusitis". Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 16 (3): 226–30. doi:10.1097/MOO.0b013e3282fdcc9a. PMID 18475076.

- Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, Cheung D, Eisenberg S, Ganiats TG, Gelzer A, Hamilos D, Haydon RC, Hudgins PA, Jones S, Krouse HJ, Lee LH, Mahoney MC, Marple BF, Mitchell CJ, Nathan R, Shiffman RN, Smith TL, Witsell DL (September 2007). "Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 137 (3 Suppl): S1–31. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2007.06.726. PMID 17761281.

- Ebell MH, McKay B, Dale A, Guilbault R, Ermias Y (March 2019). "Accuracy of Signs and Symptoms for the Diagnosis of Acute Rhinosinusitis and Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis". Annals of Family Medicine. 17 (2): 164–172. doi:10.1370/afm.2354. PMC 6411403. PMID 30858261.

- Page 674 Archived 2017-02-16 at the Wayback Machine in: Paul W. Flint, Bruce H. Haughey, John K. Niparko, Mark A. Richardson, Valerie J. Lund, K. Thomas Robbins, Marci M. Lesperance, J. Regan Thomas (2010). Cummings Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery: Head and Neck Surgery, 3-Volume Set. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323080873.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Harrison's Manual of Medicine 16/e

- Consumer Reports; American Academy of Family Physicians (April 2012). "Treating sinusitis: Don't rush to antibiotics" (PDF). Choosing wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Consumer Reports. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 11, 2012. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. "Five things physicians and patients should question" (PDF). Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2012.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Consumer Reports; American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (July 2012), "Treating sinusitis: Don't rush to antibiotics" (PDF), Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, Consumer Reports, archived (PDF) from the original on January 24, 2013, retrieved August 14, 2012CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Lemiengre MB, van Driel ML, Merenstein D, Liira H, Mäkelä M, De Sutter AI (September 2018). "Antibiotics for acute rhinosinusitis in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD006089. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006089.pub5. PMC 6513448. PMID 30198548.

- Harvey R, Hannan SA, Badia L, Scadding G (July 2007). Harvey R (ed.). "Nasal saline irrigations for the symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD006394. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006394.pub2. PMID 17636843.

- Rhinitis medicamentosa at eMedicine

- Shaikh N, Wald ER (October 2014). "Decongestants, antihistamines and nasal irrigation for acute sinusitis in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10): CD007909. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007909.pub4. PMID 25347280.

- Zalmanovici Trestioreanu A, Barua A, Pertzov B (May 2018). "Cyclamen europaeum extract for acute sinusitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5: CD011341. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011341.pub2. PMC 6494494. PMID 29750825.

- Head K, Sharp S, Chong LY, Hopkins C, Philpott C (September 2018). "Topical and systemic antifungal therapy for chronic rhinosinusitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD012453. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012453.pub2. PMC 6513454. PMID 30199594.

- Lemiengre MB, van Driel ML, Merenstein D, Young J, De Sutter AI (October 2012). "Antibiotics for clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis in adults" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD006089. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006089.pub4. PMID 23076918.

- Smith SR, Montgomery LG, Williams JW (March 2012). "Treatment of mild to moderate sinusitis". Archives of Internal Medicine. 172 (6): 510–3. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.253. PMID 22450938.

- Karageorgopoulos DE, Giannopoulou KP, Grammatikos AP, Dimopoulos G, Falagas ME (March 2008). "Fluoroquinolones compared with beta-lactam antibiotics for the treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". CMAJ. 178 (7): 845–54. doi:10.1503/cmaj.071157. PMC 2267830. PMID 18362380.

- Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, Brozek JL, Goldstein EJ, Hicks LA, Pankey GA, Seleznick M, Volturo G, Wald ER, File TM (April 2012). "IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 54 (8): e72–e112. doi:10.1093/cid/cir1043. PMID 22438350.

- "Fluoroquinolone Antibacterial Drugs: Drug Safety Communication – FDA Advises Restricting Use for Certain Uncomplicated Infections". FDA. 12 May 2016. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- Falagas ME, Karageorgopoulos DE, Grammatikos AP, Matthaiou DK (February 2009). "Effectiveness and safety of short vs. long duration of antibiotic therapy for acute bacterial sinusitis: a meta-analysis of randomized trials". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 67 (2): 161–71. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03306.x. PMC 2670373. PMID 19154447.

- Williamson IG, Rumsby K, Benge S, Moore M, Smith PW, Cross M, Little P (December 2007). "Antibiotics and topical nasal steroid for treatment of acute maxillary sinusitis: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 298 (21): 2487–96. doi:10.1001/jama.298.21.2487. PMID 18056902.

- Zalmanovici Trestioreanu A, Yaphe J (December 2013). "Intranasal steroids for acute sinusitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD005149. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005149.pub4. PMC 6698484. PMID 24293353.

- Hayward G, Heneghan C, Perera R, Thompson M (2012). "Intranasal corticosteroids in management of acute sinusitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of Family Medicine. 10 (3): 241–9. doi:10.1370/afm.1338. PMC 3354974. PMID 22585889.

- Chong LY, Head K, Hopkins C, Philpott C, Schilder AG, Burton MJ (April 2016). "Intranasal steroids versus placebo or no intervention for chronic rhinosinusitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD011996. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011996.pub2. PMID 27115217.

- Chong LY, Head K, Hopkins C, Philpott C, Burton MJ, Schilder AG (April 2016). "Different types of intranasal steroids for chronic rhinosinusitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD011993. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011993.pub2. PMID 27115215.

- Head K, Chong LY, Hopkins C, Philpott C, Burton MJ, Schilder AG (April 2016). "Short-course oral steroids alone for chronic rhinosinusitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD011991. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011991.pub2. PMID 27113367.

- Fokkens W, Lund V, Mullol J (2007). "European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2007". Rhinology. Supplement. 20 (20): 1–136. doi:10.1017/S0959774306000060. PMID 17844873.

- Thomas M, Yawn BP, Price D, Lund V, Mullol J, Fokkens W (June 2008). "EPOS Primary Care Guidelines: European Position Paper on the Primary Care Diagnosis and Management of Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2007 - a summary". Primary Care Respiratory Journal. 17 (2): 79–89. doi:10.3132/pcrj.2008.00029. PMC 6619880. PMID 18438594.

- Venekamp RP, Thompson MJ, Hayward G, Heneghan CJ, Del Mar CB, Perera R, et al. (March 2014). "Systemic corticosteroids for acute sinusitis" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD008115. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008115.pub3. PMID 24664368.

- Head K, Chong LY, Hopkins C, Philpott C, Schilder AG, Burton MJ (April 2016). "Short-course oral steroids as an adjunct therapy for chronic rhinosinusitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD011992. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011992.pub2. PMID 27115214.

- Tichenor WS (2007-04-22). "FAQ — Sinusitis". Archived from the original on 2007-11-01. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- Rimmer J, Fokkens W, Chong LY, Hopkins C (1 December 2014). "Surgical versus medical interventions for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD006991. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006991.pub2. PMID 25437000.

- Sharma R, Lakhani R, Rimmer J, Hopkins C (November 2014). "Surgical interventions for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD006990. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006990.pub2. PMID 25410644.

- Pang YT, Willatt DJ (October 1996). "Do antral washouts have a place in the current management of chronic sinusitis?". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 110 (10): 926–8. doi:10.1017/s0022215100135376. PMID 8977854.

- Stammberger H (February 1986). "Endoscopic endonasal surgery--concepts in treatment of recurring rhinosinusitis. Part I. Anatomic and pathophysiologic considerations". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 94 (2): 143–7. doi:10.1177/019459988609400202. PMID 3083326.

- Liang J, Lane AP (March 2013). "Topical Drug Delivery for Chronic Rhinosinusitis". Current Otorhinolaryngology Reports. 1 (1): 51–60. doi:10.1007/s40136-012-0003-4. PMC 3603706. PMID 23525506.

- Bailey and Love

- Anon JB (April 2010). "Upper respiratory infections". The American Journal of Medicine. 123 (4 Suppl): S16–25. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.02.003. PMID 20350632.

- Dykewicz MS, Hamilos DL (February 2010). "Rhinitis and sinusitis". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 125 (2 Suppl 2): S103–15. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.12.989. PMID 20176255.