Haemophilia B

Haemophilia B is a blood clotting disorder causing easy bruising and bleeding due to an inherited mutation of the gene for factor IX, and resulting in a deficiency of factor IX. It is less common than factor VIII deficiency (haemophilia A).[3]

| Haemophilia B | |

|---|---|

| |

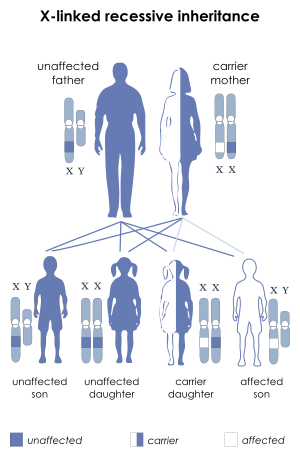

| Diagram depicting how a mother with an abnormal X-linked recessive gene (a "carrier") (white box), and a father with a normal comparable gene ("unaffected")(blue box) can result in 1)an affected son; 2)an unaffected son; 3)a carrier daughter; or 4)an unaffected daughter, each with a 25% probability. | |

| Specialty | Haematology |

| Causes | Factor IX deficiency[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Bleeding scores, Coagulation factor assays[2] |

| Treatment | Factor IX concentrate[1] |

Haemophilia B was first recognized as a distinct disease entity in 1952.[4] It is also known by the eponym Christmas disease,[1] named after Stephen Christmas, the first patient described with haemophilia B. In addition, the first report of its identification was published in the Christmas edition of the British Medical Journal.[4][5]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms include easy bruising, urinary tract bleeding (hematuria), nosebleeds (epistaxis), and bleeding into joints (hemarthrosis).[1]

Genetics

The factor IX gene is located on the X chromosome (Xq27.1-q27.2). It is an X-linked recessive trait, which explains why males are affected in greater numbers.[6][7]

In 1990, George Brownlee and Merlin Crossley showed that two sets of genetic mutations were preventing two key proteins from attaching to the DNA of people with a rare and unusual form of haemophilia B – haemophilia B Leyden – where sufferers experience episodes of excessive bleeding in childhood but have few bleeding problems after puberty.[7] This lack of protein attachment to the DNA was thereby turning off the gene that produces clotting factor IX, which prevents excessive bleeding.[7]

Pathophysiology

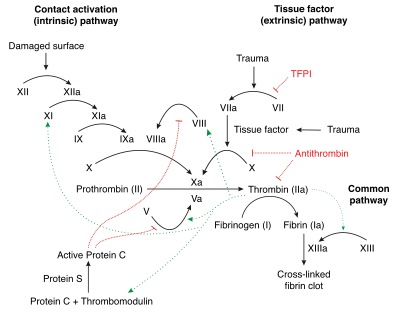

Factor IX deficiency leads to an increased propensity for haemorrhage, which can be either spontaneously or in response to mild trauma.[8]

Factor IX deficiency can cause interference of the coagulation cascade, thereby causing spontaneous hemorrhage when there is trauma. Factor IX when activated activates factor X which helps fibrinogen to fibrin conversion.[8]

Factor IX becomes active eventually in coagulation by cofactor factor VIII (specifically IXa). Platelets provide a binding site for both cofactors. This complex (in the coagulation pathway) will eventually activate factor X.[9]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis for hemophilia B can be done via the following tests/methods:[2]

- Coagulation screening test

- Bleeding scores

- Coagulation factor assays

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for this inherited condition is the following: hemophilia A, factor XI deficiency, von Willebrand disease, fibrinogen disorders and Bernard-Soulier syndrome[7]

Treatment

Treatment is given intermittently, when there is significant bleeding. It includes intravenous infusion of factor IX and/or blood transfusions. NSAIDS should be avoided once the diagnosis is made since they can exacerbate a bleeding episode. Any surgical procedure should be done with concomitant tranexamic acid.[4][10]

History

In the 1950s and 1960s, with newfound technology and gradual advances in medicine, pharmaceutical scientists found a way to take the factor IX from fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and give it to those with haemophilia B. Though they found a way to treat the disease, the FFP contained only a small amount of factor IX, requiring large amounts of FFP to treat an actual bleeding episode, which resulted in the person requiring hospitalization. By the mid-1960s scientists found a way to get a larger amount of factor IX from FFP. By the late 1960s, pharmaceutical scientists found methods to separate the factor IX from plasma, which allows for neatly packaged bottles of factor IX concentrates. With the rise of factor IX concentrates it became easier for people to get treatment at home.[11] Although these advances in medicine had a significant positive impact on the treatment of haemophilia, there were many complications that came with it. By the early 1980s, scientists discovered that the medicines they had created were transferring blood-borne viruses, such as hepatitis, and HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. With the rise of these deadly viruses, scientists had to find improved methods for screening the blood products they received from donors.In 1982, scientists made a breakthrough in medicine and were able to clone factor IX gene. With this new development it decreased the risk of the many viruses. Although the new factor was created, it wasn't available for haemophilia B patients till 1997.

Society

In 2009, an analysis of genetic markers revealed that haemophilia B was the blood disease affecting many European royal families of Great Britain, Germany, Russia and Spain: so-called "Royal Disease".[12][13]

References

- "Hemophilia B: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2016-09-21.

- Konkle, Barbara A.; Josephson, Neil C.; Nakaya Fletcher, Shelley (1 January 1993). "Hemophilia B". GeneReviews. Retrieved 7 October 2016.update 2014

- Kliegman, Robert (2011). Nelson textbook of pediatrics (19th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. pp. 1700–1. ISBN 978-1-4377-0755-7.

- "Haemophilia B (Factor IX Deficiency) information | Patient". Patient. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- Biggs R, Douglas AS, MacFarlane RG, Dacie JV, Pitney WR, Merskey C, O'Brien JR (1952). "Christmas disease: a condition previously mistaken for haemophilia". Br Med J. 2 (4799): 1378–82. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4799.1378. PMC 2022306. PMID 12997790.

- "OMIM Entry - # 306900 - HEMOPHILIA B; HEMB". omim.org. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- "Hemophilia".

- "Hemophilia B: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology". eMedicine. Medscape. 24 August 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- "Factor IX Deficiency: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". eMedicine. Medscape. 24 August 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- Beck, Norman (2009). Diagnostic hematology. London: Springer. p. 416. ISBN 9781848002951. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- Schramm, Wolfgang (November 2014). "The history of haemophilia – a short review". Thrombosis Research. 134: S4–S9. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2013.10.020. ISSN 1879-2472. PMID 24513149. – via ScienceDirect (Subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries.)

- Michael Price (8 October 2009). "Case Closed: Famous Royals Suffered From Hemophilia". ScienceNOW Daily News. AAAS. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- Evgeny I. Rogaev; et al. (8 October 2009). "Genotype Analysis Identifies the Cause of the "Royal Disease"". Science. 326 (5954): 817. Bibcode:2009Sci...326..817R. doi:10.1126/science.1180660. PMID 19815722.subscription required

Further reading

- Franchini, Massimo; Frattini, Francesco; Crestani, Silvia; Sissa, Cinzia; Bonfanti, Carlo (1 January 2013). "Treatment of hemophilia B: focus on recombinant factor IX". Biologics: Targets and Therapy. 7: 33–38. doi:10.2147/BTT.S31582. ISSN 1177-5475. PMC 3575125. PMID 23430394.

- Nathwani, Amit C.; Reiss, Ulreke M.; Tuddenham, Edward G.D.; Rosales, Cecilia; Chowdary, Pratima; McIntosh, Jenny; Della Peruta, Marco; Lheriteau, Elsa; Patel, Nishal; Raj, Deepak; Riddell, Anne; Pie, Jun; Rangarajan, Savita; Bevan, David; Recht, Michael; Shen, Yu-Min; Halka, Kathleen G.; Basner-Tschakarjan, Etiena; Mingozzi, Federico; High, Katherine A.; Allay, James; Kay, Mark A.; Ng, Catherine Y.C.; Zhou, Junfang; Cancio, Maria; Morton, Christopher L.; Gray, John T.; Srivastava, Deokumar; Nienhuis, Arthur W.; Davidoff, Andrew M. (20 November 2014). "Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Factor IX Gene Therapy in Hemophilia B". New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (21): 1994–2004. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1407309. ISSN 0028-4793. PMC 4278802. PMID 25409372.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |