Charité

The Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin is one of Europe's largest university hospitals, affiliated with Humboldt University and Free University Berlin.[3] With numerous Collaborative Research Centers (CRC) of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft it is one of Germany's most research-intensive medical institutions. From 2012 to 2019, it was ranked by Focus as the best of over 1000 hospitals in Germany.[4][5] US Newsweek ranked the Charité as fifth best hospital in the world and best in Europe (2019)[6]. More than half of all German Nobel Prize winners in Physiology or Medicine, including Emil von Behring, Robert Koch and Paul Ehrlich, have worked at the Charité.[7] Several politicians and diplomats have been treated at the Charité, including German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who underwent meniscus treatment at the Orthopaedic Department, and Julia Timoschenko from Ukraine.[8][9]

Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin | |

| |

| Motto | Forschen, Lehren, Heilen, Helfen |

|---|---|

Motto in English | Researching, teaching, healing, helping |

| Type | Public |

| Established | 1710 |

| Budget | € 1.7 billion[1] |

| Chairman | Heyo K. Kroemer[2] |

Academic staff | 4,401[1] |

Administrative staff | 8,521[1] |

| Students | 7,200[1] |

| Location | Berlin , Germany |

| Campus | Urban |

| Affiliations | Freie Universität Berlin Humboldt University of Berlin |

| Website | www |

In 2010/11 the medical schools of Humboldt University and Freie Universität Berlin were united under the roof of the Charité. The admission rate of the reorganized medical school was 5% in 2013.[10] QS World University Rankings 2019 ranked the Charité Medical School as number one for medicine in Germany and ninth best in Europe.[11] In 2019, it was announced that the Berlin Institute of Health will become part of the Charité, marking a change in the German university system by making the Charité the first university clinic which will receive direct and annual financial support by the federal state of Germany. Together with private charity donors like the Johanna Quandt's private excellence initiative (BMW) or the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, as well as financing by the State of Berlin, the new direct federal investments will become the third financial fundament for research at the Charité.[12] In addition, it is part of the Berlin University Alliance, receiving funding from the German Universities Excellence Initiative in 2019.

History

Complying with an order of King Frederick I of Prussia from 14 November 1709, the hospital was established north of the Berlin city walls in 1710 in anticipation of an outbreak of the bubonic plague that had already depopulated East Prussia. After the plague spared the city, it came to be used as a charity hospital for the poor. On 9 January 1727, Frederick William I of Prussia gave it the name Charité, meaning "charity".[13]

The construction of an anatomical theatre in 1713 marks the beginning of the medical school, then supervised by the collegium medico-chirurgicum of the Prussian Academy of Sciences.[14]

After the University of Berlin (today Humboldt University) was founded in 1810, the dean of the medical college Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland integrated the Charité as a teaching hospital in 1828.

Organization

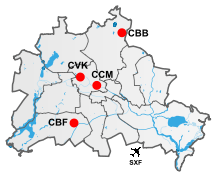

The Charité has four different campuses across the city of Berlin:

- Campus Charité Mitte (CCM) in Mitte, Berlin

- Campus Benjamin Franklin (CBF) in Lichterfelde, Berlin

- Campus Virchow Klinikum (CVK) in Wedding, Berlin

- Campus Berlin Buch (CBB) in Buch, Berlin

In 2001, the Helios Clinics Group acquired the hospitals in Buch with their 1,200 beds. Still, the Charité continues to use the campus for teaching and research and has more than 300 staff members located there. The Charité encompasses more than 100 clinics and scientific institutes, organized in 17 different departments, referred to as Charité Centers (CC):

- CC 1: Health and Human Sciences

- CC 2: Basic Sciences (First Year)

- CC 3: Dental, Oral and Maxillary Medicine

- CC 4: Charité-BIH Center for Therapy Research

- CC 5: Diagnostic Laboratory and Preventative Medicine

- CC 6: Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology and Nuclear Medicine

- CC 7: Anesthesiology, Operating-Room Management and Intensive Care Medicine

- CC 8: Surgery

- CC 9: Traumatology and Reconstructive Medicine

- CC 10: Charité Comprehensive Cancer Center

- CC 11: Cardiovascular Diseases

- CC 12: Internal Medicine and Dermatology

- CC 13: Internal Medicine, Gastroenterology and Nephrology

- CC 14: Tumor Medicine

- CC 15: Neurology, Neurosurgery, Psychiatry

- CC 16: Audiology/Phoniatrics, Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology

- CC 17: Gynecology, Perinatal, Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine with Perinatal Center & Human Genetics

Overall, 13 of those centers focus on patient care, while the rest focuses on research and teaching. The Medical History Museum Berlin has a history dating back to 1899. The museum in its current form opened in 1998 and is famous for its pathological and anatomical collection.[15]

Notable people

Many famous physicians and scientists worked or studied at the Charité. Indeed, more than half of the German Nobel Prize winners in medicine and physiology come from the Charité.[16] Forty Nobel laureates are affiliated with Humboldt University of Berlin and five with Freie Universität Berlin.

- Selmar Aschheim – gynecologist

- Heinrich Adolf von Bardeleben – surgeon

- Ernst von Bergmann - surgeon

- August Bier – surgeon

- Max Bielschowsky – neuropathologist

- Theodor Billroth – surgeon

- Otto Binswanger - psychiatrist and neurologist

- Karl Bonhoeffer - neurologist

- Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt – neurologist and neuropathologist

- Johann Friedrich Dieffenbach – surgeon

- Friedrich Theodor von Frerichs – pathologist

- Robert Froriep – anatomist

- Wilhelm Griesinger – psychiatrist and neurologist

- Hermann von Helmholtz – physician and physicist

- Joachim Friedrich Henckel – surgeon

- Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle – physician, pathologist and anatomist

- Eduard Heinrich Henoch – pediatrician

- Otto Heubner – pediatrician

- Rahel Hirsch – first female medical professor in Prussia

- Erich Hoffmann – dermatologist

- Anton Ludwig Ernst Horn – psychiatrist

- Gero Hütter – hematologist

- Friedrich Jolly – neurologist and psychiatrist

- Friedrich Kraus – internist

- Bernhard von Langenbeck – surgeon

- Karl Leonhard – psychiatrist

- Hugo Karl Liepmann – neurologist and psychiatrist

- Leonor Michaelis – biochemist and physician

- Hermann Oppenheim – neurologist

- Samuel Mitja Rapoport – biochemist and physician

- Moritz Heinrich Romberg – neurologist

- Ferdinand Sauerbruch – surgeon

- Curt Schimmelbusch – physician and pathologist

- Johann Lukas Schönlein – physician and pathologist

- Theodor Schwann – zoologist

- Ludwig Traube – physician and pathologist

- Rudolf Virchow – physician, founder of cell theory and modern pathology

- Carl Friedrich Otto Westphal – neurologist and psychiatrist

- Carl Wernicke – neurologist

- August von Wassermann – bacteriologist

- Caspar Friedrich Wolff – physiologist

- Bernhard Zondek – endocrinologist

Nobel laureates

- Emil Adolf von Behring – physiologist (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1901)

- Ernst Boris Chain – biochemist (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945)

- Paul Ehrlich – immunologist (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1908)

- Hermann Emil Fischer – chemist (Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1902)

- Werner Forssmann – physician (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1956)

- Robert Koch – physician (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1905)

- Albrecht Kossel – physician (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1910)

- Sir Hans Adolf Krebs – physician and biochemist (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1953)

- Fritz Albert Lipmann – biochemist (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1953)

- Hans Spemann – embryologist (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1935)

- Otto Heinrich Warburg – physiologist (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1931)

Medical school

In 2003 the Berlin city and state House of Representatives passed an interim law unifying the medical faculties of both Humboldt University and Freie Universität Berlin under the roof of the Charité.[17] Since 2010/11 all new medical students have been enrolled on the New Revised Medical Curriculum Programme with a length of 6 years.[18] Referred to the points needed in the German Abitur to get directly accepted, the Charité is together with Heidelberg University Medical School Germany's most competitive medical school (2016).[19] 3,17% of all Charité Medical School students are supported by the German Academic Scholarship Foundation, the highest percentage of all public German universities. The Erasmus Exchange Programme offered to Charité Medical School students includes 72 universities and is the largest in Europe.[20] Charité students can spend up to a year at a foreign medical school with exchange partners such as the Karolinska Institute, University of Copenhagen, Sorbonne University, Università di Roma La Sapienza, University of Amsterdam, and the University of Zürich. Students are also encouraged to participate in research projects, complete a dissertation, or join Charité affiliated social projects.

International partner universities

- UK: Oxford University

- UK: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

- USA: Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore

- USA: Northwestern University, Chicago

- Canada: Université de Montréal

- Australia: Monash University, Melbourne

- Japan: Chiba University

- Japan: Saitama Medical School

- Brazil: Universidade de São Paulo

- China: Tongji University, Shanghai

- China: Tongji Medical College, Wuhan

Einstein Foundation

The Charité is one of the main partners of the Einstein Foundation, which was established by the city and state of Berlin in 2009. It is a "foundation that aims to promote science and research of top international caliber in Berlin and to establish the city as a centre of scientific excellence".[21] Research fellows include:

- Thomas Südhof – biochemist (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2013)

- Brian Kobilka – chemist (Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2012)

- Edvard Moser – neuroscientist (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2014)

Television

- Charité, German television series

References

- "Leistungsbericht der Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin über das Jahr 2015 zur Umsetzung des Charité-Vertrags 2014 bis 2017" (PDF) (in German). p. 40. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- "Heyo Kroemer tritt Amt als neuer Charité-Chef an" (in German). Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- "Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin Geschichte". Archived from the original on 10 December 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2008.

- https://www.charite.de/service/pressemitteilung/artikel/detail/charite_erneut_als_deutschlands_beste_klinik_ausgezeichnet-2/

- Mayer, Kurt-Martin (21 September 2014). "Die FOCUS-Klinikliste: Die Charité ist Deutschlands bestes Krankenhaus – Gesundheits-News – FOCUS Online – Nachrichten". Focus (in German). Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- Newsweek (29 March 2019). "The Best Hospitals in the World". Newsweek. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- 2011, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. "Home". Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- "Bundeskanzlerin: Merkel musste sich am Meniskus operieren lassen". Spiegel Online. 1 April 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- Berlin, Charité-Universitätsmedizin. "Pressemitteilung". www.charite.de (in German). Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Charité führt neuen Test für Bewerber ein". Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "Medicine". Top Universities. 15 February 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- "Das BIG wird in die Charité integriert". www.tagesspiegel.de (in German). Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "History". Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. Archived from the original on 10 December 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- Einhäupl, Karl Max; Ganten, Detlev; Hein, Jakob (2010). "2 Krankenpflege". 300 Jahre Charité – im Spiegel ihrer Institute (in German). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9783110202564. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- "History of the Museum". Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- 2011, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. "Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin: Charité". www.charite.de. Archived from the original on 25 November 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "School of Medicine: Charité". www.fu-berlin.de. 3 October 2005. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- 2011, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. "New Revised Medical Curriculum". Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- Arnold, Dietmar. "hochschulstart Wintersemester 2017/18 – zentrales Verfahren". zv.hochschulstart.de (in German). Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- Heller, Birgit. "Länder und Universitäten". Erasmus (in German). Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- "Einstein Foundation Berlin – Einstein Center for Neurosciences Berlin". www.ecn-berlin.de. Retrieved 28 September 2017.