Catheter

In medicine, a catheter is a thin tube made from medical grade materials serving a broad range of functions. Catheters are medical devices that can be inserted in the body to treat diseases or perform a surgical procedure. By modifying the material or adjusting the way catheters are manufactured, it is possible to tailor catheters for cardiovascular, urological, gastrointestinal, neurovascular, and ophthalmic applications.

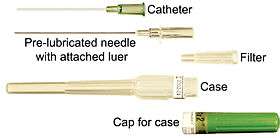

| Catheter | |

|---|---|

Catheter disassembled | |

Catheters can be inserted into a body cavity, duct, or vessel. Functionally, they allow drainage, administration of fluids or gases, access by surgical instruments, and also perform a wide variety of other tasks depending on the type of catheter.[1] The process of inserting a catheter is "catheterization". In most uses, a catheter is a thin, flexible tube ("soft" catheter) though catheters are available in varying levels of stiffness depending on the application. A catheter left inside the body, either temporarily or permanently, may be referred to as an "indwelling catheter" (for example, a peripherally inserted central catheter). A permanently inserted catheter may be referred to as a "permcath" (originally a trademark).

Uses

Placement of a catheter into a particular part of the body may allow:

- urinary catheter: draining urine from the urinary bladder as in urinary catheterization, e.g., the intermittent catheters or Foley catheter or even when the urethra is damaged as in suprapubic catheterisation.[2]

- drainage of urine from the kidney by percutaneous (through the skin) nephrostomy

- drainage of fluid collections, e.g. an abdominal abscess

- pigtail catheter: used to drain air from around the lung (pneumothorax)

- administration of intravenous fluids, medication or parenteral nutrition with a peripheral venous catheter

- angioplasty, angiography, balloon septostomy, balloon sinuplasty, cardiac electrophysiology testing, catheter ablation. Often the Seldinger technique is used.

- direct measurement of blood pressure in an artery or vein

- direct measurement of intracranial pressure

- administration of anaesthetic medication into the epidural space, the subarachnoid space, or around a major nerve bundle such as the brachial plexus

- administration of oxygen, volatile anesthetic agents, and other breathing gases into the lungs using a tracheal tube

- subcutaneous administration of insulin or other medications, with the use of an infusion set and insulin pump

- A central venous catheter is a conduit for giving drugs or fluids into a large-bore catheter positioned either in a vein near the heart or just inside the atrium.

- A Swan-Ganz catheter is a special type of catheter placed into the pulmonary artery for measuring pressures in the heart.

- An embryo transfer catheter is designed to insert fertilized embryos from in vitro fertilization into the uterus. They may vary in length from approximately 150 to 190 mm (5.9 to 7.5 in).

- An umbilical line is a catheter used in neonatal intensive care units (NICU) providing quick access to the central circulation of premature infants.

- A Tuohy-Borst adapter is a medical device used for attaching catheters to various other devices.

- A Quinton catheter is a double or triple lumen, external catheter used for hemodialysis.

- An intrauterine catheter, such as a device known as a 'tom cat', may be used to insert specially 'washed' sperm directly into the uterus in artificial insemination. A physician is required to administer this procedure.

- A Whiz Catheter is a medical grade device that does not need to be inserted but is a conduit for the passing of urine in woman who are mobility impaired and can be connected to a drainage bag or bottle

Inventors

Historical

Ancient Chinese used onion stalks, the Romans, Hindus, and Greeks used tubes of wood or precious metals.[3]

The ancient Syrians created catheters from reeds. "Catheter" (from Greek καθετήρ kathetḗr) originally referred to any instrument that was inserted, such as a plug. It comes from the Greek verb καθίεμαι kathíemai, meaning "let down", because the catheter was 'let down' into the body.

Modern

The earliest invention of the flexible catheter was during the 18th century.[4] Extending his inventiveness to his family's medical problems, Benjamin Franklin invented the flexible catheter in 1752 when his brother John suffered from bladder stones. Franklin's catheter was made of metal with segments hinged together with a wire enclosed to provide rigidity during insertion.[5][6]

According to a footnote in his letter in Volume 4 of the Papers of Benjamin Franklin (1959), Benjamin Franklin credits Francesco Roncelli-Pardino from 1720 as the inventor of a flexible catheter. In fact, Benjamin Franklin claims the flexible catheter may have been designed even earlier.[7]

An early modern application of the catheter was employed by Claude Bernard for the purpose of cardiac catheterization in 1844. The procedure involved entering a horse's ventricles via the jugular vein and carotid artery. This appears to be an earlier and modern application of the catheter because this catheter approach technique is still performed by neurosurgeons, cardiologists, and cardiothoracic surgeons.[8]

David S. Sheridan was the inventor of the modern disposable catheter in the 1940s. In his lifetime he started and sold four catheter companies and was dubbed the "Catheter King" by Forbes magazine in 1988. He is also credited with the invention of the modern "disposable" plastic endotracheal tube now used routinely in surgery. Prior to his invention, red rubber tubes were used, sterilized, and then re-used, which had a high risk of infection and thus often led to the spread of disease. As a result, Mr Sheridan is credited with saving thousands of lives.

In the early 1900s, a Dubliner named Walsh and a famous Scottish urinologist called Norman Gibbon teamed together to create the standard catheter used in hospitals today. Named after the two creators, it was called the Gibbon-Walsh catheter. The Gibbon and the Walsh catheters have been described and their advantages over other catheters shown. The Walsh catheter is particularly useful after prostatectomy for it drains the bladder without infection or clot retention. The Gibbon catheter has largely obviated the necessity of performing emergency prostatectomy. It is also very useful in cases of urethral fistula. A simple procedure such as dilatation of the urethra and passage of a Gibbon catheter often causes the fistula to close. This catheter is also of use in the treatment of urethral stricture and, as a temporary measure, in the treatment of retention of urine caused by carcinoma of the prostate.

Materials

A range of polymers are used for the construction of catheters, including silicone rubber, nylon, polyurethane, polyethylene terephthalate (PET), latex, and thermoplastic elastomers. Silicone is one of the most common choices because it is inert and unreactive to body fluids and a range of medical fluids with which it might come into contact. On the other hand, the polymer is weak mechanically, and a number of serious fractures have occurred in catheters.[9][10][11] For example, silicone is used in Foley catheters where fractures have been reported, often requiring surgery to remove the tip left in the bladder.

Polyimides are used to manufacture vascular catheters for insertion into small vessels in the neck, head and brain.

There are many different types of catheters for bladder problems. A typical modern intermittent catheter is made from polyurethane and comes in different lengths and sizes for men, women and children. The most advanced catheters have a thin hydrophilic surface coating. When immersed in water this coating swells to a smooth, slippery film making the catheter safer and more comfortable to insert. Some catheters are packed in a sterile saline solution.

Interventional procedures

A. Overview

B. Both puncture needle and obturator engaged, allowing for direct insertion.

C. Puncture needle retracted. Obturator engaged. Used for example in steady advancement of the catheter on a guidewire.

D. Both obturator and puncture needle retracted, when the catheter is in place.

E. Locking string is pulled (bottom center) and then wrapped and attach to the superficial end of the catheter.

Different catheter tips can be used to guide the catheter into the target vessel.[12]

Cardiac catheterization (cardiac cath or heart cath) is a procedure to examine how well your heart is working. A thin, hollow tube called a catheter is inserted into a large blood vessel that leads to your heart. A cardiac cath provides information on how well your heart works, identifies problems and allows for procedures to open blocked arteries. The doctor will make a needle puncture through your skin and into a large blood vessel. A small straw-sized tube (called a sheath) will be inserted into the vessel. The doctor will gently guide a catheter (a long, thin tube) into your vessel through the sheath. A video screen will show the position of the catheter as it is threaded through the major blood vessels and to the heart. You may feel some pressure in your groin, but you shouldn’t feel any pain. Various instruments may be placed at the tip of the catheter. They include instruments to measure the pressure of blood in each heart chamber and in blood vessels connected to the heart, view the interior of blood vessels, take blood samples from different parts of the heart, or remove a tissue sample (biopsy) from inside the heart.[13]

The catheter used for hemodialysis is a tunneled catheter because it is placed under the skin. There are two types of tunneled catheters: cuffed or non-cuffed. Non-cuffed tunneled catheters are used for emergencies and for short periods (up to 3 weeks). Tunneled cuffed catheters, a type recommended by the NKF for temporary access, can be used for longer than 3 weeks when: - An AV fistula or graft has been placed but is not yet ready for use. - There are no other options for permanent access. For example, when a patient's blood vessels are not strong enough for a fistula or graft. Catheters have two openings inside; one is a red (arterial) opening to draw blood from your vein and out of your body into the dialysis pathway and the other is a blue (venous) opening that allows cleaned blood to return to your body. Hemodialysis is a treatment used when your kidneys fail (Stage 5 Kidney Disease) and can no longer clean your blood and remove extra fluid from your body. A hemodialysis access or vascular access is a way to reach your blood for hemodialysis. [14]

Problems

"Even routine patient care such as catheter use can cause serious problems for patients if communication breaks down among health care workers. [Catheters are hidden beneath blankets, so physicians don’t automatically know who’s using one] Any foreign object in the body carries an infection risk, and a catheter can serve as a superhighway for bacteria to enter the bloodstream or body." — Milisa Manojlovich, a professor at the University of Michigan School of Nursing and Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation

Catheters can be difficult to clean, and therefore harbor antibiotic resistant[15] or otherwise pathogenic bacteria.

References

- Diggery, Robert (2012). Catheters: Types, applications and potential complications (medical devices and equipment. Nova Science. ISBN 1621006301.

- "MedlinePlus: Urinary catheters". U.S. National Library of Medicine. November 6, 2019.

- "MedTech Memoirs: Catheters". Advantage Business Media. June 16, 2015. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017.

- "Didusch Site - Milestones - Relief in a Tube: Catheters Remain a Steadfast Treatment for Urinary Disorders". www.urologichistory.museum. Archived from the original on January 17, 2015.

- "Benjamin Franklin: In Search of a Better World". Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on August 12, 2011.

- Hirschmann, J.V. (December 2005). "Benjamin Franklin and Medicine" (PDF). Annals of Internal Medicine. 143 (11): 830–4. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-143-11-200512060-00012.

- Huth, E.J. (2007). "Benjamin Franklin's place in the history of medicine" (PDF). Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 37 (4): 373–8.

- Baim, Donald (2005). Grossman's Cardiac Catheterization, Angiography, and Intervention. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0781755672.

- McKenzie, J. M.; Flahiff, C. M.; Nelson, C. L. (October 1, 1993). "Retention and strength of silicone-rubber catheters. A report of five cases of retention and analysis of catheter strength". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 75 (10): 1505–1507. ISSN 0021-9355. PMID 8408139. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- Agarwal, Shaleen; Gandhi, Mamatha; Kashyap, Randeep; Liebman, Scott (March 1, 2011). "Spontaneous Rupture of a Silicone Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter Presenting Outflow Failure and Peritonitis". Peritoneal Dialysis International. 31 (2): 204–206. doi:10.3747/pdi.2010.00123. ISSN 0896-8608. PMID 21427251. Archived from the original on May 8, 2018.

- Mirza, Bilal; Saleem, Muhammad; Sheikh, Afzal (August 14, 2010). "Broken Piece of Silicone Suction Catheter in Upper Alimentary Tract of a Neonate". APSP Journal of Case Reports. 1 (1): 8. ISSN 2218-8185. PMC 3417984. PMID 22953251.

- http://www.merit.com/PDFs/IMPRESS400741001-B.pdf Archived 12 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- (American Heart Association)

- (National Kidney Foundation)

- "Nobody wants to talk about catheters. Our silence could prove fatal | Mosaic". Mosaicscience.com. November 7, 2018. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Catheters. |

| Look up catheter in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Millward, Steven F. (September 2000). "Percutaneous Nephrostomy: A Practical Approach". Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 11 (8): 955–964. doi:10.1016/S1051-0443(07)61322-0.