Carotid stenting

Carotid artery stenting (CAS) is an endovascular procedure where a stent is deployed within the lumen of the carotid artery to treat narrowing of the carotid artery and decrease the risk of stroke. CAS is used to treat narrowing of the carotid artery in high-risk patients, when carotid endarterectomy is considered too risky. Carotid artery stenosis can present with no symptoms or with symptoms such as transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) or strokes.

| Carotid stenting | |

|---|---|

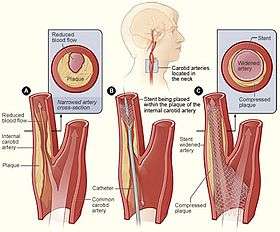

Illustration showing the process of carotid artery stenting | |

| ICD-9-CM | 00.55, 00.63, 39.90, |

Benefits

The largest clinical trial to date, CREST, compared stenting to surgery on the collective incidence of any stroke, any heart attack or death. They found that there was no significant differences out to four years of follow-up between surgery and carotid stenting when counting all three, but carotid endarterectomy (CEA) has a higher risk of heart attacks and CAS has a higher risk of minor stroke than open surgery.[1] Overall, younger patients (<70 years old) had better outcomes with stenting than with surgery. Patients had fewer heart attacks with stenting, but they did have more minor strokes. There was no difference between surgery or stenting for major (disabling) strokes.

Prior to this, several European trials have reported results in symptomatic carotid artery stenosis patients comparing surgery and stenting. A major problem with the European trials is they allowed inexperienced operators to place stents, while the surgeons performing CEA were very experienced. The SPACE trial,[2] conducted in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland found no difference in outcomes between surgery and stenting. They also noted that younger (< 67 years old) patients had better outcomes with stenting. They noted that more experienced centers had better results than inexperienced centers.

The EVA-3s[3] trial was stopped early due to an early finding that stenting was too dangerous. The trial was criticized that they used experienced surgeons and inexperienced stent physicians, so that the results may have been affected by the training of operators. Future trials ensured that the endovascular arms had more experienced endovascular operators, as seen in the CREST and SAPPHIRE trial.[1]

An interim report from ICSS[4] demonstrates no overall difference between surgery and stenting for both major strokes and death, but again did show more minor strokes (resolved within 30 days) with stents and open surgery was safer than CAS in the treatment of symptomatic carotid artery disease. A study was carried out in seven of the centers participating in ICSS to assess the incidence of ischemic brain lesions (silent infarcts) detected by diffusion-weighted MRI. They found that 73% of patients undergoing CAS with distal filter protection showed new ischemic lesions after the procedure versus 17% of those undergoing CEA. Again, the CAS operators were less experienced than the CEA operators which may have imbalanced the study.

Recently physicians have questioned the ethics and validity of European trials comparing a mature carotid surgical procedure to carotid stenting performed by inexperienced physicians.[5] In CREST, the largest trial comparing stenting to surgery in over 2,500 patients, physicians were required to demonstrate their expertise before being allowed to enroll patients in the trial. This trial showed no difference between carotid stenting and carotid surgery in average risk patients.

Most recently, a broad consensus of experts released a guideline document suggesting that in most cases, carotid stenting may be considered an alternative therapy to surgery.[6]

Procedure

Carotid stenting can be performed under general or local anesthesia. Critical steps in the procedure are vascular access, crossing the stenosis with a wire, deploying a stent across the lesion, and removing the vascular access. A number of other steps may or may not be performed, including the use of a cerebral protection device, pre- or post-stent balloon dilation and cerebral angiography.

Indications

Carotid stenting is the preferred therapy for patients who are at an increased risk with carotid surgery. High risk factors include medical comorbidities (severe heart disease, heart failure, severe lung disease, age > 75/80, etc.) and anatomic features (contralateral carotid occlusion, radiation therapy to the neck, prior ipsilateral carotid artery surgery, intra-thoracic or intracranial carotid disease) that make surgery difficult or risky.[7]

Anatomic high surgical risk:

- Contralateral carotid occlusion

- Contralateral laryngeal palsy

- Post-radiation treatment

- Previous CEA recurrent stenosis

- High cervical ICA lesions

- CCA lesions below the clavicle

- Severe tandem lesions

Co-morbid high surgical risk:

- Congestive Heart Failure (Class III/IV), and/or known severe left ventricular dysfunction <30%

- Open-heart surgery within 6 weeks

- Recent myocardial infarction (>24 hours and <4 weeks)

- Unstable angina (CCS class III/IV)

- Synchronous severe cardiac and carotid disease requiring open heart surgery and carotid revascularization

- Severe pulmonary disease to include any of the following:

- Chronic oxygen therapy

- Resting P02 of < 60 mmHg

- Baseline hematocrit > 50%

- FEV1 or DLCO < 50% of normal

- Abnormal stress test

- Age greater than 80 years

Using the criteria of successful trials, candidates are either symptomatic (TIA or stroke) patients with >50% stenosis of the carotid artery, or are asymptomatic with >80% stenosis of the internal carotid artery.

Carotid stenting may be considered an alternative to carotid surgery in average surgical risk patients, albeit with a higher risk of death or stroke as seen in the SAPPHIRE and CREST trials.[1]

Features that favor carotid stenting include non-atherosclerotic cause of the stenosis (fibrodysplasia, radiation, early post-surgical stenosis or flap) an experienced center and experienced physician performing the procedure. Features that make stent placement more difficult include significant aortic arch tortuosity, thrombus containing lesions, occluded carotid artery, heavily calcified vessels, symptomatic patients and very tortuous and twisting vessels. None of these affect open, surgical endarterectomy.

Patient selection warnings

Lesion Characteristics:

- Patients with evidence of intraluminal thrombus thought to increase the risk of plaque fragmentation and distal embolization.

- Patients whose lesion(s) may require more than two stents.

- Patients with total occlusion of the target vessel.

- Patients with highly calcified lesions resistant to PTA.

- Concurrent treatment of bilateral lesions.

Access Characteristics:

- Patients with known peripheral vascular, supra-aortic or internal carotid artery tortuosity that would preclude the use of catheter-based techniques.

- Patients in whom femoral or brachial arterial access is not possible

Patient Characteristics:

- Patients experiencing acute ischemic neurologic stroke or who experienced a large stroke within 48 hours.

- Patients with an intracranial mass lesion (i.e., abscess, tumor, or infection) or aneurysm (>9mm).

- Patients with arterio-venous malformations of the territory of the target carotid artery.

- Patients with coagulopathies.

- Patients with poor renal function, who, in the physician’s opinion, may be at high-risk for a reaction to contrast medium.

- Pregnant patients or patients under the age of 18. Patients with uncontrolled hypertension are susceptible to periprocedural complications including intracerebral hemorrhage which may be lethal[9].

Outcomes

Based on a follow-up study of CREST patients, Brott et al. found that there is no long-term (within 4 years) difference between CAS and CEA in the rate of post-treatment stroke, heart attack, or death. In the short-term (within 1 month), however, CAS has a higher risk of minor stroke, whereas CEA has a higher risk of myocardial infarction.[1] There was no difference between surgery and stenting for major strokes or death.

In another CREST patients study, Cohen et al. found that CAS is associated with better quality-of-life outcomes such as physical functioning, vitality, social functioning, physical role limitations, and pain control compared to CEA in 2 weeks and 1 month post treatment. By 1 year, however, there is no difference in quality-of-life outcomes between CAS and CEA.[8]

References

- Brott, Thomas G; Hobson, Robert W; Howard, George; Roubin, Gary S; Clark, Wayne M; Brooks, William; MacKey, Ariane; Hill, Michael D; Leimgruber, Pierre P; Sheffet, Alice J; Howard, Virginia J; Moore, Wesley S; Voeks, Jenifer H; Hopkins, L. Nelson; Cutlip, Donald E; Cohen, David J; Popma, Jeffrey J; Ferguson, Robert D; Cohen, Stanley N; Blackshear, Joseph L; Silver, Frank L; Mohr, J.P; Lal, Brajesh K; Meschia, James F (2010). "Stenting versus Endarterectomy for Treatment of Carotid-Artery Stenosis". New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (1): 11–23. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0912321. PMC 2932446. PMID 20505173.

- http://www.theheart.org/article/868833.do%5B%5D

- Mas, Jean-Louis; Chatellier, Gilles; Beyssen, Bernard; Branchereau, Alain; Moulin, Thierry; Becquemin, Jean-Pierre; Larrue, Vincent; Lièvre, Michel; Leys, Didier; Bonneville, Jean-François; Watelet, Jacques; Pruvo, Jean-Pierre; Albucher, Jean-François; Viguier, Alain; Piquet, Philippe; Garnier, Pierre; Viader, Fausto; Touzé, Emmanuel; Giroud, Maurice; Hosseini, Hassan; Pillet, Jean-Christophe; Favrole, Pascal; Neau, Jean-Philippe; Ducrocq, Xavier (2006). "Endarterectomy versus Stenting in Patients with Symptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis". New England Journal of Medicine. 355 (16): 1660–71. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa061752. PMID 17050890.

- http://www.theheart.org/article/975095.do%5B%5D

- Roffi, Marco; Sievert, Horst; Gray, William A; White, Christopher J; Torsello, Giovanni; Cao, Piergiorgio; Reimers, Bernhard; Mathias, Klaus; Setacci, Carlo; Schönholz, Claudio; Clair, Daniel G; Schillinger, Martin; Grunwald, Iris; Bosiers, Marc; Abou-Chebl, Alex; Moussa, Issam D; Mudra, Harald; Iyer, Sriram S; Scheinert, Dierk; Yadav, Jay S; Van Sambeek, Marc R; Holmes, David R; Cremonesi, Alberto (2010). "Carotid artery stenting versus surgery: Adequate comparisons?". The Lancet Neurology. 9 (4): 339–41, author reply 341–2. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70027-2. PMID 20189459.

- Brott, Thomas G; Halperin, Jonathan L; Abbara, Suhny; Bacharach, J. Michael; Barr, John D; Bush, Ruth L; Cates, Christopher U; Creager, Mark A; Fowler, Susan B; Friday, Gary; Hertzberg, Vicki S; McIff, E. Bruce; Moore, Wesley S; Panagos, Peter D; Riles, Thomas S; Rosenwasser, Robert H; Taylor, Allen J (2011). "2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS Guideline on the Management of Patients with Extracranial Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease: Executive Summary". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 57 (8): 1002–44. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.005. PMID 21288680.

- Gurm, H. S; Yadav, J. S; Fayad, P; Katzen, B. T; Mishkel, G. J; Bajwa, T. K; Ansel, G; Strickman, N. E; Wang, H; Cohen, S. A; Massaro, J. M; Cutlip, D. E (2008). "Long-term results of carotid stenting versus endarterectomy in high-risk patients". New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (15): 1572–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0708028. PMID 18403765.

- Cohen, David J; Stolker, Joshua M; Wang, Kaijun; Magnuson, Elizabeth A; Clark, Wayne M; Demaerschalk, Bart M; Sam, Albert D; Elmore, James R; Weaver, Fred A; Aronow, Herbert D; Goldstein, Larry B; Roubin, Gary S; Howard, George; Brott, Thomas G (2011). "Health-Related Quality of Life After Carotid Stenting Versus Carotid Endarterectomy". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 58 (15): 1557–65. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.05.054. PMC 3253735. PMID 21958882.