Carotid endarterectomy

Carotid endarterectomy (CEA) is a surgical procedure performed by vascular surgeons used to reduce the risk of stroke by correcting stenosis (narrowing) in the common carotid artery or internal carotid artery. Endarterectomy is the removal of material on the inside (end(o)-) of an artery.

| Carotid endarterectomy | |

|---|---|

Carotid endarterectomy specimen. The specimen is removed from within the lumen of the common carotid artery (bottom), and the internal carotid artery (left) and external carotid artery (right). | |

| ICD-9-CM | 38.1 |

| MeSH | D016894 |

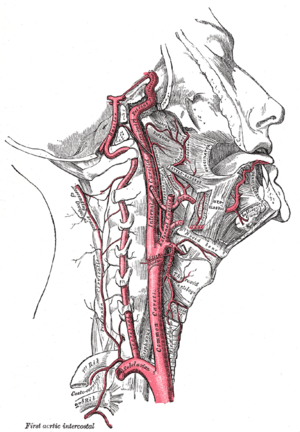

Atherosclerosis causes plaque to form within the carotid artery walls, usually at the fork where the common carotid artery divides into the internal and external carotid artery. The plaque build up can narrow or constrict the artery lumen, a condition called stenosis. Rupture of the plaque can cause the formation of a blood clot in the artery. A piece of the formed blood clot often breaks off and travels (embolizes) up through the internal carotid artery into the brain, where it blocks circulation, and can cause death of the brain tissue, a condition referred to as ischemic stroke.

Sometimes the stenosis causes temporary symptoms first, known as TIAs, where temporary ischemia occurs in the brain, spinal cord, or retina without causing an infarction.[1] Symptomatic stenosis has a high risk of stroke within the next 2 days. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend that people with moderate to severe (50–99% blockage) stenosis, and symptoms, should have "urgent" endarterectomy within 2 weeks.[2]

When the plaque does not cause symptoms, people are still at higher risk of stroke than the general population, but not as high as people with symptomatic stenosis. The incidence of stroke, including fatal stroke, is 1–2% per year. The surgical mortality of endarterectomy ranges from 1–2% to as much as 10%. Two large randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that carotid surgery done with a 30-day stroke and death risk of 3% or less will benefit asymptomatic people with ≥60% stenosis who are expected to live at least 5 years after surgery.[3][4] Surgeons are divided over whether asymptomatic people should be treated with medication alone or should have surgery.[5][6]

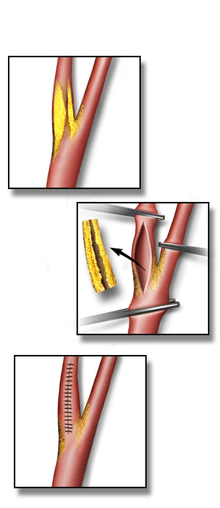

In endarterectomy, the surgeon opens the artery and removes the plaque. The plaque forms and enlarges in the inner layer of the artery, or endothelium, hence the name of the procedure which simply means removal of the endothelium of the artery. A newer procedure, endovascular angioplasty and stenting, threads a catheter up from the groin, around the aortic arch, and up the carotid artery. The catheter uses a balloon to expand the artery, and inserts a stent to hold the artery open. In several clinical trials, the 30-day incidence of heart attack, stroke, or death was significantly higher with stenting than with endarterectomy (9.6% vs. 3.9%).[7][8]

One trial found that stents and endarterectomy were comparable while another found that stents had almost double the rate of complications.[9]

Medical uses

Typically, people without symptoms must be expected to survive at least 5 years after surgery to warrant accepting the risk of surgery.[10] Current surgical best-practice restricts surgery for asymptomatic carotid stenosis to people with ≥70% carotid stenosis if the surgery can be performed with ≤3% risk of perioperative complications.[10]

The aim of CEA is to prevent ischemic stroke. As with any prevantative operation, careful evaluation of the relative benefits and risks of the procedure is required. Perioperative risks for combined 30-day mortality and stroke risk should be < 3% for asymptomatic people and ≤ 6% for symptomatic people. Symptomatic people typically have either transient ischemic attack (TIA) or minor stroke, defined as a focal neurologic defect affecting one side of the body, speech, or vision. Asymptomatic people have narrowing of their carotid arteries, but have not experienced a TIA or stroke.

Carotid stenosis is diagnosed with Doppler ultrasound studies of the neck arteries, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), computed tomography angiography (CTA), or invasive angiography. Revascularization of symptomatic stenoses has a much higher therapeutic index compared to asymptomatic lesions.

In symptomatic people for every six people treated, one major stroke would be prevented at two years (i.e. a number needed to treat (NNT) of six) for symptomatic people with a 70–99% stenosis, where percent stenosis was defined as:[11]

- percent stenosis = ( 1 − ( minimal diameter ) / ( poststenotic diameter ) ) × 100%.

Symptomatic people with less severe carotid occlusion (50–69%) had a smaller benefit, with a NNT of 22 at five years (Barclay). In addition, co-morbidity adversely affects the outcome; people with multiple medical problems have a higher post-operative mortality rate and hence benefit less from the procedure. For maximum benefit people should be operated on soon after a TIA or stroke, preferably within the first 2 weeks.

For asymptomatic people (those without TIA or strokes) the European asymptomatic carotid surgery trial (ACST) found that asymptomatic people may also benefit from the procedure, but only the group with a high grade stenosis. The key in estimating the potential benefit for revascularization in asymptomatic people is understanding the natural history of the disease, including the annual risk of stroke. Most agree that the annual risk of stroke in people with asymptomatic carotid disease is between 1% and 2%, although some people are considered to be at higher risk, such as those with ulcerated plaques. In randomized trials of CEA compared to medication therapy, it has been shown that stroke is reduced by surgery, but the benefit does not appear as a net gain for several years after the surgery is performed. This is because there are perioperative complications (stroke and death) in the surgical patients. The longer a person is expected to live after surgery, the greater the net surgical benefit.

Complications

For people to benefit from revascularization, the surgeon's complication rate (30 day stroke and death) must remain ≤3% for asymptomatic and ≤6% of symptomatic people. Other surgical complications include hemorrhage of the wound bed, which is potentially life-threatening, as swelling of the neck due to hematoma could compress the trachea. Rarely, the hypoglossal nerve can be damaged during surgery. This is likely to result in fasciculations developing on the tongue and paralysis of the affected side: on sticking it out, the person's tongue will deviate toward the affected side. Another rare but potentially serious complication is hyperperfusion syndrome because of the sudden increase in perfusion of the vasculature distal to stenosis.[12]

Contraindications

The procedure is not necessary when:

- There is complete internal carotid artery obstruction (because there is no benefit to treating chronic occlusion).

- The person has a previous complete hemispheric stroke on the ipsilateral and complete cerebrovascular territory side severe neurologic deficits (NIHSS>15), because there is no brain tissue at risk for further damage.

- People deemed unfit for the operation by the surgeon or anesthesiologist due to comorbidities.

High risk criteria for CEA include the following:

- Age ≥80 years.

- Class III/IV congestive heart failure.

- Class III/IV angina pectoris.

- Left main or multi vessel coronary artery disease.

- Need for open heart surgery within 30 days.

- Left ventricular ejection fraction of ≤30%.

- Recent (≤30-day) heart attack.

- Severe lung disease or COPD.

- Severe renal disease.

- High cervical (C2) or intrathoracic lesion.

- Prior radical neck surgery or radiation therapy.

- Contralateral carotid artery occlusion.

- Prior ipsilateral CEA.

- Contralateral laryngeal nerve injury.

- Tracheostoma.

Procedure

An incision is made on the midline side of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The incision is between 5 and 10 cm in length. The internal, common and external carotid arteries are carefully identified, controlled with vessel loops, and clamped. The lumen of the internal carotid artery is opened, and the atheromatous plaque substance removed. The artery is closed using suture and a patch to increase the size of the lumen. Hemostasis is achieved, and the overlying layers closed with suture. The skin can be closed with suture which may be visible or invisible (absorbable). Many surgeons place a temporary shunt to ensure blood supply to the brain during the procedure. The procedure may be performed under general or local anaesthesia. The latter allows for direct monitoring of neurological status by intra-operative verbal contact and testing of grip strength. With general anaesthesia, indirect methods of assessing cerebral perfusion must be used, such as electroencephalography (EEG), transcranial doppler analysis and carotid artery stump pressure monitoring. At present there is no good evidence to show any major difference in outcome between local and general anaesthesia.

Minimally invasive procedures have been developed, by threading catheters through the femoral artery, up through the aorta, then inflating a balloon to dilate the carotid artery, with a wire-mesh stent and a device to protect the brain from embolization of plaque material. The FDA has approved 7 carotid stent systems as safe and effective in people at increased risk of complications for carotid surgery and 1 carotid stent system for people at average or usual risk of carotid surgery. A study of people at high surgical risk for carotid surgery demonstrated non-inferiority for carotid stenting compared to carotid surgery.[13] The CREST trial, the largest trial comparing carotid surgery to carotid stenting in over 2,500 people found that carotid artery stenting resulted in a stroke rate of 6.4% versus 4.7% for endarterectomy at 4 years. However, carotid endarterectomy was associated with a slightly higher rate of myocardial infarction around the time of the procedure (2.3% versus 1.1%). Although the study's composite index including death, stroke, and myocardial infarction is not significantly different between the two groups, myocardial infarction was associated with less impact on quality of life as compared with stroke at one year.[14]

It is the consensus of experts in the field that carotid artery stenting should be considered an option for high risk patients who require carotid artery revascularization to prevent stroke.[15][16]

History

The endarterectomy procedure was developed and first done by the Portuguese surgeon Joao Cid dos Santos in 1946, when he operated an occluded superficial femoral artery, at the University of Lisbon. In 1951 an Argentinian surgeon repaired a carotid artery occlusion using a bypass procedure. The first endarterectomy was successfully performed by Michael DeBakey around 1953, at the Methodist Hospital in Houston, TX, although the technique was not reported in the medical literature until 1975.[17] The first case to be recorded in the medical literature was in The Lancet in 1954;[17][18] the surgeon was Felix Eastcott, a consultant surgeon and deputy director of the surgical unit at St Mary's Hospital, London, UK.[19] Eastcott's procedure was not strictly an endarterectomy as we now understand it; he excised the diseased part of the artery and then resutured the healthy ends together. Since then, evidence for its effectiveness in different patient groups has accumulated. In 2003 nearly 140,000 carotid endarterectomies were performed in the USA.

References

- Easton, J. D.; Saver, J. L.; Albers, G. W.; Alberts, M. J.; Chaturvedi, S.; Feldmann, E.; et al. (2009). "Definition and Evaluation of Transient Ischemic Attack: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists". Stroke. 40 (6): 2276–2293. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192218. ISSN 0039-2499. PMID 19423857.

- Sharon Swain, Claire Turner, Pippa Tyrrell, Anthony Rudd on behalf of the Guideline Development Group, Diagnosis and initial management of acute stroke and transient ischaemic attack: summary of NICE guidance, BMJ 2008;337:a786, doi:10.1136/bmj.a786 (Published 24 July 2008)

- Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study (ACAS) (1995). "Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis". JAMA. 273 (18): 1421–1428. doi:10.1001/jama.273.18.1421.

- Halliday A, Mansfield A, Marro J, Peto C, Peto R, Potter J, Thomas D (2004). "Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 363 (9420): 1491–1502. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(04)16146-1. PMID 15135594.

- Clinical Decisions: Management of Carotid Stenosis, N Engl J Med 358:1617–1621

- Drug Therapy Gains Favor to Avert Stroke, By THOMAS M. BURTON, Wall Street Journal, MARCH 3, 2009. Layman's summary of surgery vs. medication-only debate.

- Carotid Stenting vs. Endarterectomy: Longer-Term Outcomes Archived 2010-12-08 at the Wayback Machine JournalWatch General Medicine

- Sidawy AN, Zwolak RM, White RA, Siami FS, Schermerhorn ML, Sicard GA (2009). "Risk-adjusted 30-day outcomes of carotid stenting and endarterectomy: results from the SVS Vascular Registry". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 49 (1): 71–9. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2008.08.039. PMID 19028045.

- Study Finds Stents Effective in Preventing Strokes By RONI CARYN RABIN, New York Times, February 26, 2010.

- American Academy of Neurology (February 2013), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Academy of Neurology, retrieved August 1, 2013

- Barnett HJ; Taylor DW; Eliasziw M; et al. (November 1998). "Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators". The New England Journal of Medicine. 339 (20): 1415–1425. doi:10.1056/NEJM199811123392002. PMID 9811916.

- van Mook WN; Rennenberg RJ; Schurink GW; et al. (2005). "Cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome". Lancet Neurol. 4 (12): 877–888. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70251-9. PMID 16297845.

- Yadav JS; Wholey MH; Kuntz RE; et al. (October 2004). "Protected carotid-artery stenting versus endarterectomy in high-risk patients". N. Engl. J. Med. 351 (15): 1493–1501. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040127. PMID 15470212.

- Brott TG, Hobson RW 2nd, Howard G et al. (2010). "Stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of carotid-artery stenosis". N Engl J Med. 363: 11–23. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0912321. PMC 2932446. PMID 20505173.

- White CJ, Beckman JA, Cambria RP, Comerota AJ, Gray WA, Hobson RW, Iyer SS (2008). "Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Symposium II: controversies in carotid artery revascularization". Circulation. 118 (25): 2852–2859. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.108.191175. PMID 19106407.

- Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al. (2011). "ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS Guideline on the Management of Patients With Extracranial Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease: Executive Summary A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Stroke Association, American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, American College of Radiology, American Society of Neuroradiology, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery, Society for Vascular Medicine, and Society for Vascular Surgery Developed in Collaboration With the American Academy of Neurology and Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography". J Am Coll Cardiol. 57 (8): 1002–44. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.005. PMID 21288680.

- Friedman, SG (December 2014). "The first carotid endarterectomy". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 60 (6): 1703–8.e1–4. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2014.08.059. PMID 25238726.

- Eastcott, HH; Pickering, GW; Rob, CG (13 November 1954). "Reconstruction of internal carotid artery in a patient with intermittent attacks of hemiplegia". Lancet. 267 (6846): 994–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(54)90544-9. PMID 13213095.

- "Felix Eastcott, arterial surgeon". The Times. London. 2009-12-31.