Calf (leg)

The calf (Latin: sura) is the back portion of the lower leg in human anatomy. The muscles within the calf correspond to the posterior compartment of the leg. The two largest muscles within this compartment are known together as the calf muscle and attach to the heel via the Achilles tendon. Several other, smaller muscles attach to the knee, the ankle, and via long tendons to the toes.

| Calf | |

|---|---|

The calf is the back portion of the lower leg | |

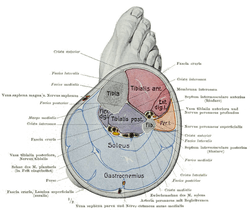

Cross-section of lower right leg, through the calf, showing its 4 compartments: anterior at upper right; lateral at center right; deep posterior at center; superficial posterior at the bottom | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | sura |

| TA | A01.1.00.039 |

| FMA | 24984 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

The calf is composed of the muscles of the posterior compartment of the leg: The gastrocnemius and soleus (composing the triceps surae muscle) and the tibialis posterior. The sural nerve provides innervation.

Clinical significance

Medical conditions that result in calf swelling among other symptoms include deep vein thrombosis[1] compartment syndrome,[2][3] Achilles tendon rupture, and varicose veins.

Idiopathic leg cramps are common and typically affect the calf muscles at night.[4] Edema also is common and in many cases idiopathic. In a small study of factory workers in good health, wearing compression garments helped to reduce edema and the pain associated with edema.[5] A small study of runners found that wearing knee-high compression stockings while running significantly improved performance.[6]

The circumference of the calf has been used to estimate selected health risks. In Spain, a study of 22,000 persons 65 or older found that a smaller calf circumference was associated with a higher risk of undernutrition.[7] In France, a study of 6265 persons 65 or older found an inverse correlation between calf circumference and carotid plaques.[8]

Calf augmentation and restoration is available, using a range of prosthesis devices and surgical techniques.

History

Etymology

Calf and calf of the leg are documented in use in Middle English, respectively, circa 1350 and 1425.[9]

Historically, the absence of calf, meaning a lower leg without a prominent calf muscle, was regarded by some authors as a sign of inferiority: it is well known that monkeys have no calves, and still less do they exist among the lower orders of mammals.[10]

Training

The calf training routine includes a set of simple and effective exercises.

Springs. The exercise is performed by standing straight and slowly rising on toes. The heels should be lifted off the floor as high as possible. The recommended number of sets is 3–4, and the number of repetitions is 30. Also, 100 times in a row can be performed as an alternative. To complicate the exercise, one can use additional weights, such as light dumbbells or bottles with water. If keeping balance is difficult, the weight can be held in one hand, and the other hand can be used to lean against the wall or the back of a chair. Another more complicated variation of this exercise is performed first with one leg, and then with the other leg.

Calf raises on the platform. For this exercise, a step platform is needed. A thick book or just a stair step can be also used for this purpose. The starting position is standing on the edge of a step with the heels hanging down. One should rise on tiptoe and then lower the body down, while stretching the ankle to the limit and touching the heels to the floor.

There is a possibility of maneuver on a step platform: one can vary the position of the toes to target different portions of the calves. The gastrocnemius muscle has 2 heads: medial and lateral. With the feet forward, equal amounts of the medial and lateral heads are targeted. To target the inner portion of the calves (the medial head), the toes should be pointed outwards. The outer calves (the lateral head) are worked out with the toes pointed inwards.

The more complicated option of this exercise implies performing the calf raises with the full range of motion, holding the weight in one hand and leaning against the wall with the other hand for balance.

Tiptoe walking. This is an easy exercise that involves rising up on tiptoes and walking with small steps. One should avoid bending the knees.

Stair walking. Walking up and down the stairs is a good way to work out the calf muscles. 15–30 minutes are enough for this kind of activity.

Jumping rope. This exercise is usually performed by gymnasts and boxers. It is important to jump until the calf muscles burn.

Weighted jumps. This exercise greatly works the calves and is performed by jumping out of a squat position while holding a couple of dumbbells in hands.

Weighted Squats. The squats are done with the dumbbells in hands until the leg muscles burn.

Seated calf raises. The soleus muscle that makes up three quarters of the lower leg muscles is targeted only in the seated position. The exercises that are performed in a standing position target the outer portion of the calf, and this is just a quarter of its overall volume.

This variation of calf raises can be done both in the gym by using an exercise machine, and at home by sitting on a chair with some weight on the knees. The exercise should be performed in a slow pace.

Pistol squat. This exercise is suitable for advanced athletes, because it is difficult to perform. One should hold onto something with a hand, extend one of the legs forward, and squat on the other leg as many times as possible.

Jogging. Jogging is a good way to work out the calves very fast.

Cycling, skiing, tennis, roller skating, ice skating. Each of these kinds of sports is "calf-forming" and yields an amazing result for leg muscles. Unlike the previous exercises, these are outdoor activities.

The calf exercises should be performed every 3–4 days. They can be alternated and interchanged to avoid getting used to the load.

General Workout Tips

Before any serious activity, including doing calf-building exercises, the muscles and joints should be properly warmed up.

Aerobic exercises should be performed at the beginning of a workout. A workout should end with calf strengthening exercises to stimulate their growth, and stretching that involves taking a wide step backward, placing the heel on the floor, and bending the torso forward. Each leg should be stretched for 10–20 seconds.

The calf exercises should be performed with maximum range of motion.

The load should be changed regularly. Getting used to the load can lower the effectiveness of workouts, therefore, diversifying the exercises is a good way to keep progressing.

The calves should be worked out two or three times a week in order for the muscles to recover.

The muscle load during calf raises can be increased by shifting the body weight to the toes.

The calf-building exercises can be complicated by pausing for five counts at the top of the rise.

One should avoid overtraining to prevent cramps.

The calf muscles slowly respond to the physical load and require more time to work them out compared to other body muscles. The stable results can be achieved due to hard work.

External links

References

- David Simel; Drummond Rennie; Robert Hayward; Sheri A Keitz (2008). The rational clinical examination: Evidence-based clinical diagnosis. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 500. ISBN 978-0-07-159030-3. page 229

- Drey IA, Baruch H (February 2008). "Acute compartment syndrome of the calf presenting after prolonged decubitus position". Orthopedics. 31 (2): 184. doi:10.3928/01477447-20080201-08. PMID 19292184.

- Hartgens F, Hoogeveen AR, Brink PR (August 2008). "[Athletes with exercise-related pain at the medial side of the lower leg]". Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde (in Dutch). 152 (33): 1839–43. PMID 18783163.

- Young G (2009). "Leg cramps". Clinical Evidence. 2009. PMC 2907778. PMID 19445755.

- Blättler W, Kreis N, Lun B, Winiger J, Amsler F (2008). "Leg symptoms of healthy people and their treatment with compression hosiery". Phlebology. 23 (5): 214–21. doi:10.1258/phleb.2008.008014. PMID 18806203.

- Kemmler W, von Stengel S, Köckritz C, Mayhew J, Wassermann A, Zapf J (January 2009). "Effect of compression stockings on running performance in men runners". Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 23 (1): 101–5. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31818eaef3. PMID 19057400.

- Cuervo M, Ansorena D, García A, González Martínez MA, Astiasarán I, Martínez JA (2009). "[Assessment of calf circumference as an indicator of the risk for hyponutrition in the elderly]". Nutrición Hospitalaria : Organo Oficial de la Sociedad Española de Nutrición Parenteral y Enteral (in Spanish). 24 (1): 63–7. PMID 19266115.

- Debette S, Leone N, Courbon D, Gariépy J, Tzourio C, Dartigues JF, Ritchie K, Alpérovitch A, Ducimetière P, Amouyel P, Zureik M (November 2008). "Calf circumference is inversely associated with carotid plaques" (PDF). Stroke: A Journal of Cerebral Circulation. 39 (11): 2958–65. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.520106. PMID 18703804.

- Hans Kurath (1959). Middle English dictionary. University of Michigan Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-472-01031-8. page 20

- Maria Montessori (1913). Pedagogical anthropology. Frederic Taber Cooper. Frederick A. Stokes Company. p. 508. page 311