Calcium gluconate

Calcium gluconate is a mineral supplement and medication.[1] As a medication it is used by injection into a vein to treat low blood calcium, high blood potassium, and magnesium toxicity.[2][1] Supplementation is generally only required when there is not enough calcium in the diet.[3] Supplementation may be done to treat or prevent osteoporosis or rickets.[1] It can also be taken by mouth but is not recommended for injection into a muscle.[1]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | KAL see um GLUE koe nate |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | by mouth, IV, topical |

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| E number | E578 (acidity regulators, ...) |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.524 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

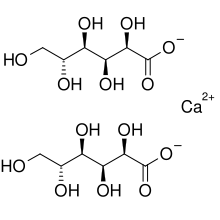

| Formula | C12H22CaO14 |

| Molar mass | 430.373 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 120 °C (248 °F) (decomposes) |

| Solubility in water | slowly soluble mg/mL (20 °C) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Side effects when injected include slow heart rate, pain at the site of injection, and low blood pressure.[3] When taken by mouth side effects may include constipation and nausea.[1] Blood calcium levels should be measured when used and extra care should be taken in those with a history of kidney stones.[3] At normal doses use is regarded as safe in pregnancy and breastfeeding.[1][4] Calcium gluconate is made by mixing gluconic acid with calcium carbonate or calcium hydroxide.[5]

Calcium gluconate came into medical use in the 1920s.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective medicines needed in a health system.[7] Calcium gluconate is available as a generic medication.[2] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.21–1.34 per one-gram vial, 10 ml of 100 mg/ml (10% solution).[8] In the United Kingdom this amount costs the NHS about 0.65 pounds.[2]

Medical uses

Low blood calcium

10% calcium gluconate solution (given intravenously) is the form of calcium most widely used in the treatment of low blood calcium. This form of calcium is not as well absorbed as calcium lactate,[9] and it only contains 0.93% (930 mg/dl) calcium ion (defined by 1 g weight solute in 100 ml of solution to make 1% solution w/v). Therefore, if the hypocalcemia is acute and severe, calcium chloride is given instead.

High blood potassium

Calcium gluconate is used as a cardioprotective agent in people with high blood potassium levels, with one alternative being the use of calcium chloride.[10] It is recommended when the potassium levels are high (>6.5 mmol/l) or when the electrocardiogram (ECG) shows changes due to high blood potassium.[2]

Though it does not have an effect on potassium levels in the blood, it reduces the excitability of cardiomyocytes, thereby lowering the likelihood of cardiac arrhythmias.[11]

Magnesium sulfate overdose

It is also used to counteract an overdose of Epsom salts magnesium sulfate,[12] which is often administered to pregnant women in order to prophylactically prevent seizures (as in a patient experiencing preeclampsia). Magnesium sulfate is no longer given to pregnant women who are experiencing premature labor in order to slow or stop their contractions (other tocolytics are now used instead due to better efficacy and side effect profiles). Excess magnesium sulfate results in magnesium sulfate toxicity, which results in both respiratory depression and a loss of deep tendon reflexes (hyporeflexia).

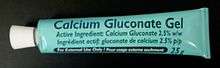

Hydrofluoric acid burns

Gel preparations of calcium gluconate are used to treat hydrofluoric acid burns.[13][14] This is because calcium gluconate reacts with hydrofluoric acid to form insoluble, non-toxic calcium fluoride.

Black widow spider bites

Historically, IV calcium gluconate was used as an antidote for black widow spider envenomation, often in conjunction with muscle relaxants.[15] This therapy, however, has since been shown to be ineffective.[16][17]

Cardiac arrest

While intravenous calcium has been used in cardiac arrest its general use is not recommended.[1] Cases of cardiac arrest in which it is still recommended include high blood potassium, low blood calcium such as may occur following blood transfusions, and calcium channel blocker overdose.[1] There is the potential that general use could worsen outcomes.[1] If calcium is used calcium chloride is generally the recommended form.[1]

Side effects

Calcium gluconate side effects include nausea, constipation, and upset stomach. Rapid intravenous injections of calcium gluconate may cause hypercalcaemia, which can result in vasodilation, cardiac arrhythmias, decreased blood pressure, and bradycardia. Extravasation of calcium gluconate can lead to cellulitis. Intramuscular injections may lead to local necrosis and abscess formation.[18]

It is also reported that this form of calcium increases renal plasma flow, diuresis, natriuresis,[19][20] glomerular filtration rate,[21] and prostaglandin E2 and F1-alpha levels.[22]

Society and culture

Shortages of medical calcium gluconate were reported in November 2012 and November 2015 in the United States.[10][23]

See also

- Calcium lactate gluconate

References

- "Calcium Salts". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. pp. 680, 694. ISBN 9780857111562.

- WHO Model Formulary 2008 (PDF). World Health Organization. 2009. p. 497. ISBN 9789241547659. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "Calcium gluconate Use During Pregnancy | Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- Bhattacharya, Suvendu (2014). Conventional and Advanced Food Processing Technologies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 391. ISBN 9781118406304. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017.

- Tegethoff, F. Wolfgang (2012). Calcium Carbonate: From the Cretaceous Period into the 21st Century. Birkhäuser. p. 308. ISBN 9783034882453. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017.

- World Health Organization (2019). "World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). hdl:10665/325771. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Calcium Gluconate". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Spencer, H.; Scheck, J.; Lewin, I.; Samachson, J. (1966). "Comparative absorption of calcium from calcium gluconate and calcium lactate in man". The Journal of Nutrition. 89 (3): 283–292. doi:10.1093/jn/89.3.283. PMID 4288031.

- Faine; Miller (December 2013). "The Calcium Quandary". Emergency Physicians Monthly. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- Parham, W. A.; Mehdirad, A. A.; Biermann, K. M.; Fredman, C. S. (2006). "Hyperkalemia revisited". Texas Heart Institute Journal / From the Texas Heart Institute of St. Luke's Episcopal Hospital, Texas Children's Hospital. 33 (1): 40–47. PMC 1413606. PMID 16572868.

- Omu AE, Al-Harmi J, Vedi HL, Mlechkova L, Sayed AF, Al-Ragum NS (2008). "Magnesium sulphate therapy in women with pre-eclampsia and eclampsia in Kuwait". Med Princ Pract. 17 (3): 227–32. doi:10.1159/000117797. PMID 18408392.

- el Saadi MS, Hall AH, Hall PK, Riggs BS, Augenstein WL, Rumack BH (1989). "Hydrofluoric acid dermal exposure". Vet Hum Toxicol. 31 (3): 243–7. PMID 2741315.

- Roblin I, Urban M, Flicoteau D, Martin C, Pradeau D (2006). "Topical treatment of experimental hydrofluoric acid skin burns by 2.5% calcium gluconate". J Burn Care Res. 27 (6): 889–94. doi:10.1097/01.BCR.0000245767.54278.09. PMID 17091088.

- Pestana, Carlos Dr. Pestana Surgery Notes Kaplan Medical 2013

- Offerman, Steven (2011). "The Treatment of Black Widow Spider Envenomation with Antivenin Latrodectus Mactans: A Case Series". The Permanente Journal. 15 (3): 76–81. doi:10.7812/tpp/10-136. PMC 3200105. PMID 22058673.

- Clark, Richard (July 1992). "Clinical presentation and treatment of black widow spider envenomation: A review of 163 cases". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 21 (7): 782–787. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(05)81021-2. PMID 1351707.

- Yui-Ming Lam; Hung-Fat Tse; Chu-Pak Lau (April 2001). "Continuous Calcium Chloride Infusion for Massive Nifedipine Overdose". Chest. 119 (4): 1280–1282. doi:10.1378/chest.119.4.1280. PMID 11296202.

- Ruilope LM; Oliet A; Alcázar JM; Hernández E; Andrés A; Rodicio JL; García-Robles R; Martínez J; Lahera V; Romero JC. (December 1989). "Characterization of the renal effects of an intravenous calcium gluconate infusion in normotensive volunteers". J Hypertens Suppl. 7 (6): S170–1. doi:10.1097/00004872-198900076-00081. PMID 2632708.

- Bernardi M, Di Marco C, Trevisani F, Fornalè L, Andreone P, Cursaro C, Baraldini M, Ligabue A, Tamè MR, Gasbarrini G (July 1993). "Renal sodium retention during upright posture in preascitic cirrhosis". Gastroenterology. 105 (1): 188–193. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(93)90025-8. PMID 8514034.

- Wong F, Massie D, Colman J, Dudley F (March 1993). "Glomerular hyperfiltration in patients with well-compensated alcoholic cirrhosis". Gastroenterology. 104 (3): 884–900. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(93)91026-e. PMID 8440439.

- Lahera V, Fiksen-Olsen MJ, Romero JC (February 1990). "Stimulation of renin release by intrarenal calcium infusion". Hypertension. 15 (2): 149–152. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.15.2_suppl.i149. PMID 2404858.

- "FDA Drug Shortages". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

External links

- "Calcium gluconate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.