Breast imaging

In medicine, breast imaging is the representation or reproduction of a breast's form. There are various methods of breast imaging.

.jpg)

X-ray

Mammography

Mammography is the process of using low-energy X-rays (usually around 30 kVp) to examine the human breast, which is used as a diagnostic and screening tool. The goal of mammography is the early detection of breast cancer, typically through detection of characteristic masses and/or microcalcifications. For the average woman, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended (2009) mammography every two years in women between the ages of 50 and 74.[1] The American College of Radiology and American Cancer Society recommend yearly screening mammography starting at age 40.[2] The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (2012) and the European Cancer Observatory (2011) recommends mammography every 2–3 years between 50 and 69.[3][4] These task force reports point out that in addition to unnecessary surgery and anxiety, the risks of more frequent mammograms include a small but significant increase in breast cancer induced by radiation.[5][6] Additionally, mammograms should not be done with any increased frequency in people undergoing breast surgery, including breast enlargement, mastopexy, and breast reducation.[7] The Cochrane Collaboration (2013) concluded that the trials with adequate randomisation did not find an effect of mammography screening on total cancer mortality, including breast cancer, after 10 years. The authors of systematic review write: "If we assume that screening reduces breast cancer mortality by 15% and that overdiagnosis and overtreatment is at 30%, it means that for every 2000 women invited for screening throughout 10 years, one will avoid dying of breast cancer and 10 healthy women, who would not have been diagnosed if there had not been screening, will be treated unnecessarily. Furthermore, more than 200 women will experience important psychological distress including anxiety and uncertainty for years because of false positive findings." The authors conclude that the time has come to re-assess whether universal mammography screening should be recommended for any age group.[8] They thus state that universal screening may not be reasonable. The Nordic Cochrane Collection, which in 2012 reviews updated research to state that advances in diagnosis and treatment make mammography screening less effective today. They state screening is “no longer effective.” They conclude that “it therefore no longer seems reasonable to attend” for breast cancer screening at any age, and warn of misleading information on the internet.

Mammography has a false-negative (missed cancer) rate of between 7 and 12 percent.[9] This is partly due to dense tissues obscuring the cancer and the fact that the appearance of cancer on mammograms has a large overlap with the appearance of normal tissues. A meta-analysis review of programs in countries with organized screening found 52% over-diagnosis.Digital breast tomosynthesis

Digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) can provide a higher diagnostic accuracy compared to conventional mammography. In DBT, like conventional mammography, compression is used to improve image quality and decreases radiation dose. The laminographic imaging technique dates back to the 1930s and belongs to the category of geometric or linear tomography.[10]

Because the data acquired are very high resolution (85 – 160 micron typical ), much higher than CT, DBT is unable to offer the narrow slice widths that CT offers (typically 1-1.5 mm). However, the higher resolution detectors permit very high in-plane resolution, even if the Z-axis resolution is less. The primary interest in DBT is in breast imaging, as an extension to mammography, where it offers better detection rates with little extra increase in radiation.[11][12]

Tomosynthesis is now Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for use in breast cancer screening.[13]

Xeromammography

Xeromammography is a photoelectric method of recording an x-ray image on a coated metal plate, using low-energy photon beams, long exposure time, and dry chemical developers. It is a form of xeroradiography.[14]

Galactography

Galactography is a medical diagnostic procedure for viewing the milk ducts. The standard treatment of galactographically suspicious breast lesions is to perform a surgical intervention on the concerned duct or ducts: if the discharge clearly stems from a single duct, then the excision of the duct (microdochectomy) is indicated;[15] if the discharge comes from several ducts or if no specific duct could be determined, then a subareolar resection of the ducts (Hadfield's procedure) is performed instead.[15] To avoid infection, galactography should not be performed when the nipple discharge contains pus.[16]

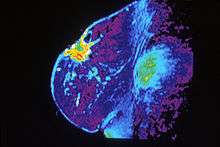

MRI

Breast MRI, an alternative to mammography, has shown substantial progress in the detection of breast cancer. The available literature suggests that the sensitivity of contrast-enhanced breast MRI in detection of cancer is considerably higher than that of either radiographic mammography or ultrasound and is generally reported to be in excess of 94%.[17]

The specificity (the confidence that a lesion is cancerous and not a false positive) is only fair ('modest'),[18] (or 37%-97%[17]) thus a positive finding by MRI should not be interpreted as a definitive diagnosis.

The reports of 4,271 breast MRIs from eight large scale clinical trials were reviewed in 2006.[19]

Ultrasound

Breast ultrasound is the use of medical ultrasonography to perform imaging of the breast. It can be considered either a diagnostic or a screening procedure.[20] It may be used either with or without a mammogram.[21]

Scintimammography

Scintimammography is a type of breast imaging test that is used to detect cancer cells in the breasts of some women who have had abnormal mammograms, or for those who have dense breast tissue, post-operative scar tissue or breast implants, but is not used for screening or in place of a mammogram. Rather, it is used when the detection of breast abnormalities is not possible or not reliable on the basis of mammography and ultrasound. In the scintimammography procedure, a woman receives an injection of a small amount of a radioactive substance called technetium 99 sestamibi. This substance is preferably taken up by cancerous tissues, making them show brightly on the images.[22]

References

- "Breast Cancer: Screening". United States Preventive Services Task Force.

- "Breast Cancer Early Detection". cancer.org. 2013-09-17. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- "Recommendations on screening for breast cancer in average-risk women aged 40–74 years". Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-02-11. Retrieved 2015-09-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Breast Cancer: Screening". United States Preventive Services Task Force. Archived from the original on 2013-06-16.

- Friedenson B (March 2000). "Is mammography indicated for women with defective BRCA genes? Implications of recent scientific advances for the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of hereditary breast cancer". MedGenMed. 2 (1): E9. PMID 11104455.

- American Society of Plastic Surgeons (24 April 2014), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Society of Plastic Surgeons, archived from the original on 19 July 2014, retrieved 25 July 2014

- Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ (2013). "Screening for breast cancer with mammography". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6 (6): CD001877. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub5. PMC 6464778. PMID 23737396.

- "Mammogram Accuracy - Accuracy of Mammograms". ww5.komen.org. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- Dedicated Computed Tomography of the Breast: Image Processing and Its Impact on Breast Mass Detectability. Qing Xia. 2007. ISBN 0549663193 pp.4

- Smith AP, Niklason L, Ren B, Wu T, Ruth C, Jing Z. Lesion Visibility in Low Dose Tomosynthesis. In: Digital mammography : 8th international workshop, IWDM 2006, Manchester, UK, June 18–21, 2006 : proceedings. Astley, S, Brady, M, Rose, C, Zwiggelaar, R (Eds.) (Springer, New York, 2006) pp.160.

- Lång, K; Andersson, I; Zackrisson, S (2014). "Breast cancer detection in digital breast tomosynthesis and digital mammography—a side-by-side review of discrepant cases". The British Journal of Radiology. 87 (1040): 20140080. doi:10.1259/bjr.20140080. ISSN 0007-1285. PMC 4112403. PMID 24896197.

- "Selenia Dimensions 3D System – P080003, US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), February 11, 2011

- Xeromammography at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Nigel Rawlinson; Derek Alderson (29 September 2010). Surgery: Diagnosis and Management. John Wiley & Sons. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-4443-9122-0.

- "Breast ductography". radiopaedia.org. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Breast

- DeMartini W, Lehman C, Partridge S (April 2008). "Breast MRI for cancer detection and characterization: a review of evidence-based clinical applications". Acad Radiol. 15 (4): 408–16. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2007.11.006. PMID 18342764.

- Lehman CD (2006). "Role of MRI in screening women at high risk for breast cancer". Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 24 (5): 964–70. doi:10.1002/jmri.20752. PMID 17036340.

- A. Thomas Stavros; Cynthia L. Rapp; Steve H. Parker (1 January 2004). Breast ultrasound. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-397-51624-7. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- "Breast ultrasound: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- Nass, Sharyl J.; Henderson, I. Craig; Cancer, Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Technologies for the Early Detection of Breast (2001). Mammography and beyond: developing technologies for the early detection of breast cancer. National Academies Press. pp. 106–. ISBN 978-0-309-07283-0. Retrieved 17 July 2011.