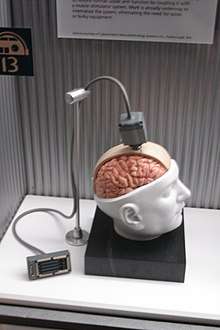

Brain transplant

A brain transplant or whole-body transplant is a procedure in which the brain of one organism is transplanted into the body of another organism. It is a procedure distinct from head transplantation, which involves transferring the entire head to a new body, as opposed to the brain only. Theoretically, a person with advanced organ failure could be given a new and functional body while keeping their own personality, memories, and consciousness through such a procedure.

No human brain transplant has ever been conducted. Neurosurgeon Robert J. White has grafted the head of a monkey onto the headless body of another monkey. EEG readings showed the brain was later functioning normally. It was thought to prove that the brain was an immunologically privileged organ, as the host's immune system did not attack it at first,[1] but immunorejection caused the monkey to die after nine days.[2] Brain transplants and similar concepts have also been explored in various forms of science fiction.

Existing challenges

One of the most significant barriers to the procedure is the inability of nerve tissue to heal properly; scarred nerve tissue does not transmit signals well (this is why a spinal cord injury is so devastating). Research at the Wistar Institute of the University of Pennsylvania involving tissue-regenerating mice (known as MRL mice) may provide pointers for further research as to how to regenerate nerves without scarring. It is possible that a completely clean cut will not generate scarred tissue.

Alternatively, a brain–computer interface can be used connecting the subject to their own body. A study[3] using a monkey as a subject shows that it is possible to directly use commands from the brain, bypass the spinal cord and enable hand function. An advantage is that this interface can be adjusted after the surgical interventions are done where nerves can not be reconnected without surgery.

Also, for the procedure to be practical, the age of the donated body must be sufficient: an adult brain cannot fit into a skull that has not reached its full growth, which occurs at age 9–12 years.

When organs are transplanted, aggressive rejection by the host's immune system can occur. Because immune cells of the CNS contribute to the maintenance of neurogenesis and spatial learning abilities in adulthood, the brain has been hypothesized to be an immunologically privileged (unrejectable) organ.[4])[5][6] However, immunorejection of a functional transplanted brain has been reported in monkeys.[7]

Partial brain transplant

In 1982, Dr. Dorothy T. Krieger, chief of endocrinology at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City, achieved success with a partial brain transplant in mice.[8]

In 1998, a team of surgeons from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center attempted to transplant a group of brain cells to Alma Cerasini, who had suffered a severe stroke that caused the loss of mobility in her right limbs as well as limited speech. The team's hope was that the cells would correct the listed damage.[9]

In science fiction

The whole-body transplant is just one of several means of putting a consciousness into a new body that have been explored in science fiction.

In the film Get Out (2017), written and directed by Jordan Peele, a young, white woman, Rose Armitage (Allison Williams), lures her young, black boyfriend, Chris Washington (Daniel Kaluuya), to her family's estate to be auctioned-off for a brain transplant procedure that enables older, white residents of the Armitage community to obtain a pseudo-immortality in a black person's body. The Armitage family is the founder of the cult The Order of the Coagula, in which Missy Armitage (Catherine Keener), a psychiatrist, uses hypnosis to subdue the consciousness of black persons to The Sunken Place, and Dean Armitage (Bradley Whitford), a neurosurgeon, transplants the brain of the white person into the black person's body. Due to the human body's need for motor functions, only a partial brain transplant is possible. The Sunken Place is essential to suppressing the conscious minds of the hosts while the brain tissue is implanted into their skulls. Once the brain transplant has been completed, the white person's consciousness takes control over the black host body; meanwhile, the consciousness of the black person remains in The Sunken Place. While in the Sunken Place, the black person's consciousness is completely intact and aware of what is going on, yet has no control over their body.

In Maxwell Atoms' Cartoon Network series Evil Con Carne (2003-2004), Hector Con Carne was reduced to a brain and a stomach and both of them were put in jars attached to the body of a Russian circus bear. Hector's brain is the main character of the cartoon.

Edgar Rice Burroughs' The Mastermind of Mars involves a surgeon who does this as his main operation, and a man from Earth, the narrator and main character, who is trained to do it as well.

In Neil R. Jones Professeur Jameson stories (1931), the main character is the last earthman, whose brain is saved by some alien cyborgs called the Zoromes, and is inserted into a robotic body, making him immortal.

Robert Heinlein's 1970 science fiction novel, I Will Fear No Evil, features a main character named Johann Sebastian Bach Smith whose entire brain is transplanted into his deceased secretary's skull.

Matthew Mather's "The Dreaming Tree" features Royce Lowell-Vandeweghe who wakes up after an accident to find he has been the fourth full body transplant performed by Dr. Danesti of the Eden Corporation. The rest of the book is about his physical recovery, and he ends up having the memories of Jake Hawkins the person whose body his head is now connected to.

A similar procedure often found in science fiction is the transfer of one consciousness to another without moving the brain. This is found in many sources, most often a body swap between two characters of an ongoing television series; it occurs in the original Star Trek series twice, in the X-Files episode Dreamland, in the Doctor Who serial "Mindwarp" and the episode "New Earth", and in Freaky Friday, Farscape, Stargate SG-1, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Dollhouse, Red Dwarf, Avatar, Dark Shadows; even in Archie comics. Since there is no movement of the brain(s), this is not quite the same as a whole-body transplant.

In the horror film The Skeleton Key, the protagonist, Caroline, discovers that the old couple she is looking after are poor Voodoo witch doctors who stole the bodies of two young, privileged children in their care using a ritual which allows a soul to swap bodies. Unfortunately the evil old couple also trick Caroline and their lawyer into the same procedure, and both end up stuck in old dying bodies unable to speak while the witch doctors walk off with their young bodies.

In the Spanish "destape" film Desembraga a fondo, the brain of the protagonist, Fernando Esteso, is transplanted into his brother's skull.

In Anne Rice's The Tale of the Body Thief, the vampire Lestat discovers a man, Raglan James, who can will himself into another person's body. Lestat demands that the procedure be used on him to allow him to be human once again, but soon finds that he has made an error and is forced to recapture James in his vampiric form so he can take his body back.

Similar in many ways to this is the idea of mind uploading, promoted by Marvin Minsky and others with a mechanistic view of natural intelligence and an optimistic outlook regarding artificial intelligence. It is also a goal of Raëlism, a small cult based in Florida, France, and Quebec. While the ultimate goal of transplanting is transfer of the brain to a new body optimized for it by genetics, proteomics, and/or other medical procedures, in uploading the brain itself moves nowhere and may even be physically destroyed or discarded; the goal is rather to duplicate the information patterns contained within the brain.

Another similar literary theme, though different from either procedure described above, is the transplanting of a human brain into an artificial, usually robotic, body. Examples of this include: Caprica; Fullmetal Alchemist; Ghost in the Shell; RoboCop; the DC Comics superhero Robotman; the Cybermen from the Doctor Who television series; the cymeks in the Legends of Dune series; or full-body cyborgs in many manga or works in the cyberpunk genre. In one episode of Star Trek, Spock's Brain is stolen and installed in a large computer-like structure; and in "I, Mudd" Uhura is offered immortality in an android body. The novel Harvest of Stars by Poul Anderson features many central characters who undergo such transplants, and deals with the difficult decisions facing a human contemplating such a procedure. In the Star Wars expanded universe the shadow droids were created by taking the brains of grievously wounded TIE fighter pilot aces. After surgically transplanting them into a protective cocoon filled with nutrient fluids. they were surgically connected to cybernetic hardware that gave them external sensors, flight control and tactical computers that augmented their reflexes beyond the biological limit; at the cost of their humanity. Emperor Palpatine also imbued them with the dark side giving them a sixth sense, and making them into extensions of his own will.

See also

- Cyborgs in fiction (for stories of brains transplanted into wholly artificial bodies)

- Donovan's Brain

- Isolated brain

- Robotics

- Robert J. White

References

- "What Would Happen in a Brain Transplant?".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 February 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- C. Ethier, E. R. Oby, M. J. Bauman, L. E. Miller: Restoration of grasp following paralysis through brain-controlled stimulation of muscles. Nature, April 2012. Archived 21 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Ziv, Y.et al (2006). Nature Neuroscience, Immune cells contribute to the maintenance of neurogenesis and spatial learning abilities in adulthood 9, 268 - 275.

- Lou Jacobson: A Mind is a Terrible Thing to Waste. Lingua Franca, August 1997.

- Mike Darwin: But What Will The Neighbors Think? A Discourse On The History And Rationale Of Neurosuspension. Cryonics, October 1988.

- McCrone, John (December 2003). "Monkey Business". Lancet Neurology. 2 (12): 772. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(03)00596-9. PMID 14636785. Archived from the original on February 28, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

(As reproduced at author's personal webpage)

- Ap (18 June 1982). "Transplant Success Reported With Part of a Mouse's Brain". The New York Times. San Francisco. p. 9. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- Vedantam, Shankar. "Artificial Brain Cells Implanted In Patient The Procedure Is The First Of Its Kind. Doctors Hope Eventually To Treat Brain Disorders This Way". philly.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

External links

- Dr Robert White, profile by David Bennun in The Sunday Telegraph Magazine, 2000

- Today / Brain Transplants (BBC Radio4)

- FieldNotes: A mind is a terrible thing to waste, by Lou Jacobson (Lingua Franca)

- Dr. Robert J. White to Discuss "Rise and Fall of the Human Brain" (Lakeland Community College)

- From Science Fiction to Science: 'The Whole Body Transplant' (New York Times)

- Spinal cord regeneration

- Researchers Stretch Nerve Fibers to New Limits (Fox News)

- Spinal Cord Bridge Bypasses Injury To Restore Mobility (EmaxHealth)

- Cancer-Causing Protein May Heal Damaged Spinal Cord & Brain Cells (Newswise.com)

- Swiss make breakthrough in spinal research: Novartis has started clinical trials into spinal cord regeneration (swissinfo.ch)