Brachial plexus block

Brachial plexus block is a regional anesthesia technique that is sometimes employed as an alternative or as an adjunct to general anesthesia for surgery of the upper extremity. This technique involves the injection of local anesthetic agents in close proximity to the brachial plexus, temporarily blocking the sensation and ability to move the upper extremity. The subject can remain awake during the ensuing surgical procedure, or s/he can be sedated or even fully anesthetized if necessary.

| Brachial plexus block | |

|---|---|

Video of a brachial plexus block, using a portable ultrasound scanning device for localization of the nerves of the brachial plexus | |

| ICD-9-CM | 04.81 |

| MeSH | D009407 |

There are several techniques for blocking the nerves of the brachial plexus. These techniques are classified by the level at which the needle or catheter is inserted for injecting the local anesthetic — interscalene block on the neck, supraclavicular block immediately above the clavicle, infraclavicular block below the clavicle and axillary block in the axilla (armpit).[1]

Indications

General anesthesia may result in low blood pressure, undesirable decreases in cardiac output, central nervous system depression, respiratory depression, loss of protective airway reflexes (such as coughing), need for tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation, and residual anesthetic effects. The most important advantage of brachial plexus block is that it allows for the avoidance of general anesthesia and therefore its attendant complications and side effects. Although brachial plexus block is not without risk, it usually affects fewer organ systems than general anesthesia.[2] Brachial plexus blockade may be a reasonable option when all of the following criteria are met:

- Surgery is expected to be limited to a region between the midpoint of the shoulder and the fingers

- There are no contraindications to a block such as infection at the intended injection site, significant bleeding disorder, anxiety, allergy or hypersensitivity to local anesthetics

- There will not be a need to perform an examination of the function of the blocked nerves immediately following the surgical procedure

- The patient prefers this technique over other available and reasonable approaches

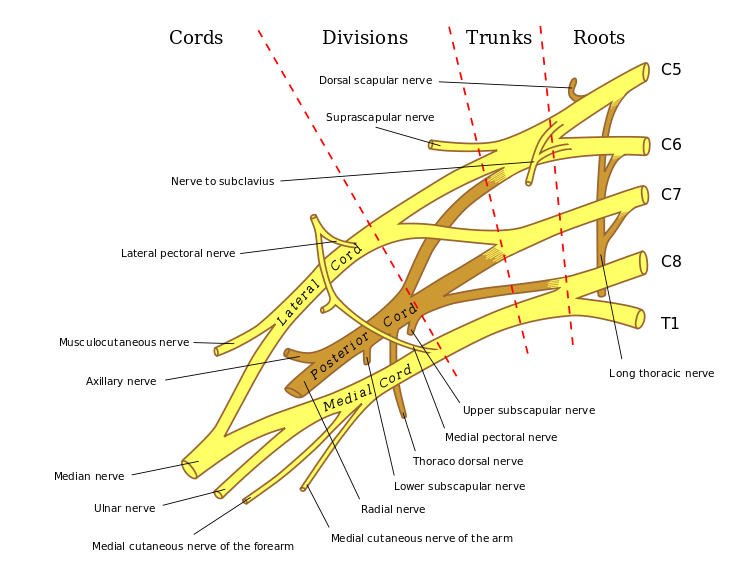

Anatomy

The brachial plexus is formed by the ventral rami of C5-C6-C7-C8-T1, occasionally with small contributions by C4 and T2. There are multiple approaches to blockade of the brachial plexus, beginning proximally with the interscalene block and continuing distally with the supraclavicular, infraclavicular, and axillary blocks. The concept behind all of these approaches to the brachial plexus is the existence of a sheath encompassing the neurovascular bundle extending from the deep cervical fascia to slightly beyond the borders of the axilla.[1]

Techniques

Brachial plexus block is typically performed by an anesthesiologist. To achieve an optimal block, the tip of the needle should be close to the nerves of the plexus during the injection of local anesthetic solution. Commonly employed techniques for obtaining such a needle position include transarterial, elicitation of a paresthesia, and use of a peripheral nerve stimulator or a portable ultrasound scanning device.[3] If the needle is close to or contacts a nerve, the subject may experience a paresthesia (a sudden tingling sensation, often described as feeling like "pins and needles" or like an electric shock) in the arm, hand, or fingers. Injection close to the point of elicitation of such a paresthesia may result in a good block.[3] A peripheral nerve stimulator connected to an appropriate needle allows emission of electric current from the needle tip. When the needle tip is close to or contacts a motor nerve, characteristic contraction of the innervated muscle may be elicited.[3] Modern portable ultrasound devices allow the user to visualize internal anatomy, including the nerves to be blocked, neighboring anatomic structures and the needle as it approaches the nerves. Observation of local anesthetic surrounding the nerves during ultrasound-guided injection is predictive of a successful block.[4] Appropriate block per site-specific procedure are listed in the following table:[5]

| Procedure Site | Interscalene | Supraclavicular | Infraclavicular | Axillary1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoulder2 | ++ | +3 | ||

| Arm2 | + | ++ | + | |

| Elbow2 | ++ | ++ | + | |

| Forearm2 | + | ++ | ++ | |

| Hand2 | + | + | ++ |

1. Include musculocutaneous nerve 2. Include T1-T2 if block is anesthetic 3. Include C3-C4 if block is anesthetic

Interscalene block

The interscalene block is performed by injecting local anesthetic to the nerves of the brachial plexus as it passes through the groove between the anterior and middle scalene muscles, at the level of the cricoid cartilage. This block is particularly useful in providing anesthesia and postoperative analgesia for surgery to the clavicle, shoulder, and arm. Advantages of this block include rapid blockade of the shoulder region, and relatively easily palpable anatomical landmarks. Disadvantages of this block include inadequate anesthesia in the distribution of the ulnar nerve, which makes this an unreliable block for operations involving the forearm and hand.[1]

- Side effects

Temporary paresis (impairment of the function) of the thoracic diaphragm occurs in virtually all people who have undergone interscalene or supraclavicular brachial plexus block. Significant respiratory impairment can be demonstrated in these people by pulmonary function testing.[6] In certain people — such as those with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease — this can result in respiratory failure requiring tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation until the block dissipates.[7] Horner's syndrome may be observed if the local anesthetic solution tracks cephalad and blocks the stellate ganglion. This may be accompanied by difficulty swallowing and vocal cord paresis. These signs and symptoms are transient however, and do not commonly result in any long-term problems, although they may be significantly distressing to patients until the effects subside.

- Contraindications

Contraindications include severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,[7] and paresis of the phrenic nerve on the opposite side as the block.[8]

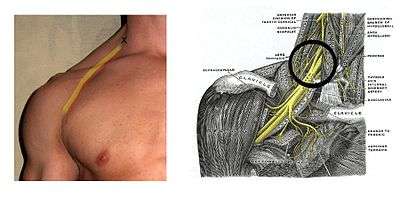

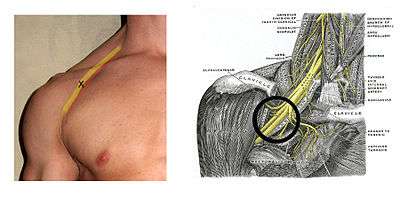

Supraclavicular block

Providing a rapid onset of dense anesthesia of the arm with a single injection, the supraclavicular block is ideal for operations involving the arm and forearm, from the lower humerus down to the hand. The brachial plexus is most compact at the level of the trunks formed by the C5–T1 nerve roots, so nerve block at this level has the greatest likelihood of blocking all of the branches of the brachial plexus. This results in rapid onset times and, ultimately, high success rates for surgery and analgesia of the upper extremity, excluding the shoulder.[9]

Surface landmarks can be used to identify the appropriate location for injection of local anesthetic, which is typically lateral to (outside) the lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and above the clavicle, with the first rib generally considered to represent the limit below which the needle must not be directed (the pleural cavity and uppermost part of the lung are located at this level). Palpation or ultrasound visualization of the subclavian artery just above the clavicle provides a useful anatomic landmark for locating the brachial plexus, which is lateral to the artery at this level.[9] Proximity to the brachial plexus can be determined using by elicitation of a paresthesia, use of a peripheral nerve stimulator, or ultrasound guidance.[10]

Compared to the interscalene block, the supraclavicular block — despite eliciting a more complete block of the median, radial ulnar and musculocutaneous nerves — does not improve postoperative analgesia. However, the supraclavicular block is often quicker to perform and may result in fewer side effects than the interscalene block. Compared to the infraclavicular block and axillary blocks, the successful achievement of adequate anesthesia for surgery of the upper extremity is about the same with supraclavicular block.[10]

Unlike the interscalene block — which results in diaphragmatic hemiparesis in all subjects — only half of those who undergo supraclavicular block experience this side effect. Disadvantages of the supraclavicular block include the risk of pneumothorax, which is estimated to be between 1%–4% when using paresthesia or peripheral nerve stimulator guided techniques. Ultrasound guidance allows the operator to visualize the first rib and the pleura, thereby helping to ensure that the needle does not puncture the pleura; this presumably reduces the risk of pneumothorax.[10]

Infraclavicular block

For infraclavicular block, current evidence suggests that — when using a peripheral nerve stimulator for nerve localization — a double-stimulation technique is better than a single-stimulation technique. When compared to a multiple-stimulation axillary block, infraclavicular block provides similar efficacy. However it may be associated with a shorter performance time and less procedure-related pain for the patient.[10]

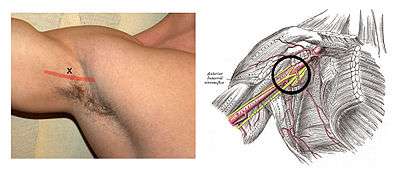

Axillary block

The axillary block is particularly useful in providing anesthesia and postoperative analgesia for surgery to the elbow, forearm, wrist, and hand. The axillary block is also the safest of the four main approaches to the brachial plexus, as it does not risk paresis of the phrenic nerve, nor does it have the potential to cause pneumothorax.[11] In the axilla, the nerves of the brachial plexus and the axillary artery are enclosed together in a fibrous sheath which is a continuation of the deep cervical fascia. The easily palpated axillary artery thus serves as a reliable anatomical landmark for this block, and the injection of local anesthetic close to this artery frequently leads to a good block of the brachial plexus. The axillary block is commonly performed due to its ease of performance and relatively high success rate.[3]

Disadvantages of the axillary block include inadequate anesthesia in the distribution of the musculocutaneous nerve. This nerve supplies motor function to the biceps, brachialis, and coracobrachialis muscles and one of its branches supplies sensation to the skin of the forearm. If the musculocutaneous nerve is missed, it may be necessary to block this nerve separately. This can be accomplished by using a peripheral nerve stimulator to identify the location of the nerve as it passes through the coracobrachialis muscle. The intercostobrachial nerves (which are branches of the second and third intercostal nerves) are also frequently missed with the axillary block. Because these nerves supply sensation to the skin of the medial and posterior aspects of the arm and axilla, a tourniquet on the arm may be poorly tolerated in such cases. Subcutaneous injection of local anesthetic over the medial aspect of the arm in the axilla helps patients tolerate an arm tourniquet by blocking these nerves.

Single-injection techniques provide unreliable blockade in the areas supplied by the musculocutaneous and radial nerves. Current evidence suggests that a triple-stimulation technique — with injections on the musculocutaneous, median and radial nerves — is the best technique for the axillary block.[10]

Methods of nerve localization

Despite the fact that people have been performing brachial plexus blocks for over a hundred years,[12] there is as yet no clear evidence to support the assertion that one method of nerve localization is better than another. There are however numerous case reports documenting cases in which use of a portable ultrasound scanning device has detected abnormal anatomy that would otherwise not have been evident using a "blind" approach. On the other hand, use of ultrasound may create a false sense of security in the operator, which may lead to errors, especially if the needle tip is not adequately visualized at all times.[9]

For interscalene block, it is not clear whether nerve stimulation provides a better interscalene block than elicitation of paresthesiae.[10] However, a recent study using ultrasound to follow the spread of local anesthetic demonstrated an improved success rate of the block (relative to blocks done with nerve stimulator alone) even at the inferior roots of the plexus.[1]

For supraclavicular block, nerve stimulation with a minimal threshold of 0.9 mA can offer a dependable block.[10] Although ultrasound-guided supraclavicular block has been shown to be a safe alternative to the peripheral nerve stimulator guided technique, there is little evidence to support that ultrasound guidance provides a better block, or is associated with fewer complications.[9] There is some evidence to suggest that the use of ultrasound guidance in combination with nerve stimulation can shorten the performance time of supraclavicular block.[10]

For axillary block, success rates are greatly improved with multiple injection techniques whether using nerve stimulation or ultrasound guidance.[11]

Special situations

The duration of a "single-shot" brachial plexus block is highly variable, commonly lasting anywhere from 45 minutes to 24 hours. The block can be extended by placing an indwelling catheter, which may be connected to a mechanical or electronic infusion pump for continuous administration of local anesthetic solution. A catheter may be inserted at the interscalene, supraclavicular, infraclavicular or axillary location, depending on the desired location of nerve block. The infusion of local anesthetic can be programmed to be a continuous flow or patient-controlled analgesia. In some cases, people can maintain the catheters and infusions at home after release from the facility where the surgery was performed.[1]

Complications

As with any procedure involving disruption of the integrity of the skin, brachial plexus block can be associated with infection or bleeding. In people who are using anticoagulant agents, there is a greater risk of complications related to bleeding.[1]

Complications associated with brachial plexus block include intra-arterial or intravenous injection, which can lead to local anesthetic toxicity. This may be characterized by serious central nervous system problems such as epileptic seizure, central nervous system depression, and coma.[13] Cardiovascular effects of local anesthetic toxicity include slowing of the heart rate and impairment of its ability to pump blood through the circulatory system, which may lead to circulatory collapse. In severe cases, cardiac dysrhythmia, cardiac arrest and death may occur.[14] Other rare but serious complications from brachial plexus block include pneumothorax and persistent paresis of the phrenic nerve.[15]

Complications associated with interscalene and supraclavicular blocks include inadvertent subarachnoid or epidural injection of local anesthetic, which can result in respiratory failure.[15]

Because of the close proximity of the lung to the brachial plexus at the level of the clavicle, the complication most often associated with this block is pneumothorax — with a risk as high as 6.1%.[9] Further complications of supraclavicular block include subclavian artery puncture, and spread of local anesthetic to cause paresis of the stellate ganglion, the phrenic nerve and recurrent laryngeal nerve.[9]

Alternatives

Depending on the circumstances, alternatives to brachial plexus block may include general anesthesia, monitored anesthesia care, Bier block, or local anesthesia.

History

In 1855, Friedrich Gaedcke (1828–1890) became the first to chemically isolate cocaine, the most potent alkaloid of the coca plant. Gaedcke named the compound "erythroxyline".[16][17] In 1884, Austrian ophthalmologist Karl Koller (1857–1944) instilled a 2% solution of cocaine into his own eye and tested its effectiveness as a local anesthetic by pricking the eye with needles.[18] His findings were presented a few weeks later at annual conference of the Heidelberg Ophthalmological Society.[19] The following year, William Halsted (1852–1922) performed the first brachial plexus block.[20][21] Using a surgical approach in the neck, Halsted applied cocaine to the brachial plexus.[22] In January 1900, Harvey Cushing (1869–1939) — who was at that time one of Halsted's surgical residents — applied cocaine to the brachial plexus prior to dividing it, during a forequarter amputation for sarcoma.[23]

The first percutaneous supraclavicular block was performed in 1911 by German surgeon Diedrich Kulenkampff (1880–1967).[12] Just as his older colleague August Bier (1861–1949) had done with spinal anesthesia in 1898,[24] Kulenkampff subjected himself to the supraclavicular block.[12] Later that year, Georg Hirschel (1875–1963) described a percutaneous approach to the brachial plexus from the axilla.[25] In 1928, Kulenkampff and Persky published their experiences with a thousand blocks without apparent major complications. They described their technique with the patient in the sitting position or in the supine position with a pillow between the shoulders. The needle was inserted above the midpoint of the clavicle where the pulse of the subclavian artery could be felt and it was directed medially toward the second or third thoracic spinous process.[26]

By the late 1940s, clinical experience with brachial plexus block in both peacetime and wartime surgery was extensive,[27] and new approaches to this technique began to be described. For example, In 1946, F. Paul Ansbro was the first to describe a continuous brachial plexus block technique. He secured a needle in the supraclavicular fossa and attached tubing connected to a syringe through which he could inject incremental doses of local anesthetic.[28] The subclavian perivascular block was first described by Winnie and Collins in 1964.[29] This approach became popular due to its lower risk of pneumothorax compared to the traditional Kulenkampff approach. The infraclavicular approach was first developed by Raj. In 1977, Selander described a technique for continuous brachial plexus block using an intravenous catheter secured in the axilla.[30]

See also

Notes

- Fisher, L; Gordon, M (2011). "Anesthesia for hand surgery" (PDF). In Wolfe, SW; Hotchkiss, RN; Pederson, WC; Kozin, SH (eds.). Green's Operative Hand Surgery. 1 (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. pp. 25–40. ISBN 978-1-4160-5279-1.

- Boedeker, BH; Rung, GW (1995). "Regional anesthesia" (PDF). In Zajtchuk, R; Bellamy, RF; Grande, CM (eds.). Textbook of Military Medicine, Part IV: Surgical Combat Casualty Care. 1: Anesthesia and Perioperative Care of the Combat Casualty. Washington, DC: Borden Institute. pp. 251–86.

- Winnie, AP (1990). "Perivascular techniques of brachial plexus block". Plexus anesthesia: perivascular techniques of brachial plexus block. I (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company. pp. 126–7. ISBN 9780721611723.

- Kapral S, Krafft P, Eibenberger K, Fitzgerald R, Gosch M, Weinstabl C (1994). "Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular approach for regional anesthesia of the brachial plexus" (PDF). Anesthesia and Analgesia. 78 (3): 507–13. doi:10.1213/00000539-199403000-00016. PMID 8109769.

- Morgan, GE; Mikhail, MS; Murray, MJ (2006). "Peripheral nerve blocks". In Morgan, GE; Mikhail, MS; Murray, MJ (eds.). Clinical Anesthesiology (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 283–308. ISBN 978-0071423588.

- Finucane, BT; Tsui, BCH (2007). Finucane, BT (ed.). Complications of regional anesthesia (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC. pp. 121–48. ISBN 978-0387375595.

- Urmey, W (2006). "Pulmonary complications". In Neal, JM; Rathmell, J (eds.). Complications in regional anesthesia and pain medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier. pp. 147–56. ISBN 9781416023920.

- Amutike, D (1998). "Interscalene brachial plexus block". Practical Procedures. 1998 (9). Archived from the original on 2011-09-26.

- Macfarlane, A; Brull, R (2009). "Ultrasound guided supraclavicular block" (PDF). The Journal of New York School of Regional Anesthesia. 12: 6–10.

- De Tran QH, Clemente A, Doan J, Finlayson RJ (2007). "Brachial plexus blocks: a review of approaches and techniques". Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 54 (8): 662–74. doi:10.1007/BF03022962. PMID 17666721.

- Satapathy, AR; Coventry, DM (2011). "Axillary Brachial Plexus Block". Anesthesiology Research and Practice. 2011: 1–5. doi:10.1155/2011/173796. PMC 3119420. PMID 21716725.

- Kulenkampff, D (1911). "Zur anästhesierung des plexus brachialis" [On anesthesia of the brachial plexus]. Zentralblatt für Chirurgie (in German). 38: 1337–40.

- Mulroy, M (2002). "Systemic toxicity and cardiotoxicity from local anesthetics: incidence and preventive measures" (PDF). Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 27 (6): 556–61. doi:10.1053/rapm.2002.37127. PMID 12430104. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-19.

- Mather, LE; Copeland, SE; Ladd, LA (2005). "Acute toxicity of local anesthetics: underlying pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic concepts" (PDF). Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 30 (6): 553–66. doi:10.1016/j.rapm.2005.07.186. PMID 16326341.

- Urmey, WF (2009). "Pulmonary complications of interscalene brachial plexus blocks" (PDF). Lecture notes: 2009 symposium. New York: The New York School of Regional Anesthesia. Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- Gaedcke, F (1855). "Ueber das Erythroxylin, dargestellt aus den Blättern des in Südamerika cultivirten Strauches Erythroxylon Coca Lam". Archiv der Pharmazie. 132 (2): 141–50. doi:10.1002/ardp.18551320208.

- Zaunick, R (1956). "Early history of cocaine isolation: Domitzer pharmacist Friedrich Gaedcke (1828–1890); contribution to Mecklenburg pharmaceutical history". Beitr Gesch Pharm Ihrer Nachbargeb. 7 (2): 5–15. PMID 13395966.

- Koller, K (1884). "Über die verwendung des kokains zur anästhesierung am auge" [On the use of cocaine for anesthesia on the eye]. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift (in German). 34: 1276–1309.

- Karch, SB (2006). "Genies and furies". A brief history of cocaine from Inca monarchs to Cali cartels : 500 years of cocaine dealing (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 51–68. ISBN 978-0849397752.

- Halsted, WS (1885-09-12). "Practical comments on the use and abuse of cocaine; suggested by its invariably successful employment in more than a thousand minor surgical operations". New York Medical Journal. 42: 294–5.

- Crile, GW (1897). "Anesthesia of nerve roots with cocaine". Cleveland Medical Journal. 2: 355.

- Borgeat, A (2006). "All roads do not lead to Rome". Anesthesiology. 105 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1097/00000542-200607000-00002. PMID 16809983.

- Cushing, HW (1902). "I. On the Avoidance of Shock in Major Amputations by Cocainization of Large Nerve-Trunks Preliminary to their Division. With Observations on Blood-Pressure Changes in Surgical Cases". Annals of Surgery. 36 (3): 321–45. doi:10.1097/00000658-190209000-00001. PMC 1430733. PMID 17861171.

- Bier, A (1899). "Versuche über cocainisirung des rückenmarkes" [Experiments on the cocainization of the spinal cord]. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Chirurgie (in German). 51 (3–4): 361–9. doi:10.1007/BF02792160.

- Hirschel, G (1911-07-18). "Die anästhesierung des plexus brachialis fuer die operationen an der oberen extremitat" [Anesthesia of the brachial plexus for operations on the upper extremity]. Munchener Medizinische Wochenschrift (in German). 58: 1555–6.

- Kulenkampff, D; Persky, MA (1928). "Brachial plexus anaesthesia: its indications, technique, and dangers". Annals of Surgery. 87 (6): 883–91. doi:10.1097/00000658-192806000-00015. PMC 1398572. PMID 17865904.

- de Pablo, JS; Diez-Mallo, J (1948). "Experience with Three Thousand Cases of Brachial Plexus Block: Its Dangers: Report of a Fatal Case". Annals of Surgery. 128 (5): 956–64. doi:10.1097/00000658-194811000-00008. PMC 1513923. PMID 17859253.

- Ansbro, FP (1946). "A Method of Continuous Brachial Plexus Block". American Journal of Surgery. 71 (6): 716–22. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(46)90219-x. PMID 20983091.

- Winnie AP, Collins VJ (1964). "The subclavian perivascular technique of brachial plexus anesthesia". Anesthesiology. 25 (3): 35–63. doi:10.1097/00000542-196405000-00014. PMID 14156576.

- Selander, D (1977). "Catheter technique in axillary plexus block: presentation of a new method". Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 21 (4): 324–9. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.1977.tb01226.x. PMID 906787.

Further reading

- Bonica, JJ; Moore, DC (1950). "Brachial plexus block anesthesia" (PDF). Current Researches in Anesthesia and Analgesia. 29 (5): 241–53. doi:10.1213/00000539-195011000-00043. PMID 14778281.

- Marhofer P, Greher M, Kapral S (2005). "Ultrasound guidance in regional anaesthesia" (PDF). British Journal of Anaesthesia. 94 (1): 7–17. doi:10.1093/bja/aei002. PMID 15277302.

- Marhofer P, Harrop-Griffiths W, Kettner SC, Kirchmair L (2010). "Fifteen years of ultrasound guidance in regional anaesthesia: part 1" (PDF). British Journal of Anaesthesia. 104 (5): 538–46. doi:10.1093/bja/aeq069. PMID 20364022.

- Marhofer P, Harrop-Griffiths W, Kettner SC, Kirchmair L (2010). "Fifteen years of ultrasound guidance in regional anaesthesia: Part 2-recent developments in block techniques" (PDF). British Journal of Anaesthesia. 104 (6): 673–83. doi:10.1093/bja/aeq086. PMID 20418267.

- Williams SR, Chouinard P, Arcand G, Harris P, Ruel M, Boudreault D, Girard F (2003). "Ultrasound guidance speeds execution and improves the quality of supraclavicular block" (PDF). Anesthesia & Analgesia. 97 (5): 1518–23. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000086730.09173.CA. PMID 14570678.

- Winnie, AP (1970). "Interscalene brachial plexus block". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 49 (3): 455–66. doi:10.1213/00000539-197005000-00029. PMID 5534420.