Bosentan

Bosentan is a dual endothelin receptor antagonist used in the treatment of pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH). It is licensed in the United States, the European Union and other countries by Actelion Pharmaceuticals for the management of PAH under the trade name Tracleer.

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Tracleer |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605001 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 50% |

| Protein binding | >98% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 5 hours |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.171.206 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

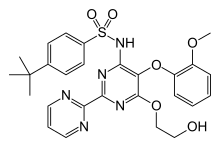

| Formula | C27H29N5O6S |

| Molar mass | 551.614 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Bosentan is available as film-coated tablets (62.5 mg or 125 mg) or as dispersable tablets for oral suspension (32 mg).[1] The dispersable tablets should be dispersed in a small amount of water before administration.[1]

Medical uses

Bosentan is used to treat people with moderate pulmonary arterial hypertension and to reduce the number of digital ulcers — open wounds on especially on fingertips and less commonly the knuckles — in people with systemic scleroderma.[1][2][3]

Bosentan causes harm to fetuses and pregnant women must not take it, and women must not become pregnant while taking it (Pregnancy Category X). It may render hormonal contraceptives ineffective so other forms of birth control must be used.[1][2]

In the US it is only available from doctors who follow an FDA-mandated risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) with respect to risks to fetuses and its risks of causing liver damage. The doctor must document a negative pregnancy test for women before prescribing the drug, counsel about contraception, and give regular pregnancy tests.[4] Because there is a high risk that bosentan causes liver damage, the REMS plan also requires pre-testing for elevated transaminases and regular testing while the drug is being taken.[4] Bosentan is also contraindicated in patients taking glyburide due to an increased risk of increased liver enzymes and liver damage when these two agents are taken together.[1]

Adverse effects

In addition to the risk of causing birth defects and of causing liver damage, bosentan has a high risk of causing edema, pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, decreasing sperm counts, and decreases in hemoglobin and hematocrit.[1][2]

Very common adverse effects (occurring in more than 10% of people) include headache, elevated transaminases, and edema. Common adverse effects (between 1% and 10% of people) include anemia, reduced hemoglobin, hypersensitivity reactions, skin inflammation, itchiness, rashes, red skin, flushing, fainting, heart palpitations, low blood pressure, nasal congestion, gastro-esophageal reflux disease, and diarrhea.[1][2]

Mechanism of action

Bosentan is a competitive antagonist of endothelin-1 at the endothelin-A (ET-A) and endothelin-B (ET-B) receptors. Under normal conditions, endothelin-1 binding of ET-A receptors causes constriction of the pulmonary blood vessels.[5] Conversely, binding of endothelin-1 to ET-B receptors has been associated with both vasodilation and vasoconstriction of vascular smooth muscle, depending on the ET-B subtype (ET-B1 or ET-B2) and tissue.[6] Bosentan blocks both ET-A and ET-B receptors, but is thought to exert a greater effect on ET-A receptors, causing a total decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance.[1]

Pharmacokinetics

Absolute bioavailability of bosentan is about 50% in healthy subjects.[7] Peak plasma concentration of bosentan with the dispersable tablets for oral suspension is 14% less on average compared to peak concentration of the oral tablets.[1]

Bosentan is a substrate of CYP3A4 and CYP2C9. CYP2C19 may also play a role in its metabolism.[1] It is also a substrate of the hepatic uptake transporter organic anion-transporting polypeptides (OATPs) OATP1B1, OATP1B3, and OATP2B1.[8][9]

Elimination of bosentan is mostly hepatic, with minimal contribution from renal and fecal excretion.[10]

Use of bosentan with cyclosporine is contraindicated because cyclosporine A has been shown to markedly increase serum concentration of bosentan.[1]

History

Bosentan was studied in heart failure in a trial called REACH-1 that was terminated early in 1997 due to toxicity at the dose that was being studied; as of 2001 the results of that trial had not been published.[11]

It was approved for PAH in the US in 2001[1] and in Europe in 2002.[2]

By 2013 worldwide sales of bosentan were $1.57 billion. The patents on bosentan started expiring in 2015.[12]

See also

References

- "US Bosentan label" (PDF). FDA. September 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2018. For label updates see FDA index page for NDA 021290

- "Tracleer (bosentan) 62.5 mg and 125mg film-coated tablets". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. May 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- Abraham, S; Steen, V (2015). "Optimal management of digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 11: 939–47. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S82561. PMC 4474386. PMID 26109864.

- "Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS)". FDA. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- Givertz, MM; Colucci, WS; LeJemtel, TH; Gottlieb, SS; Hare, JM; Slawsky, MT; Leier, CV; Loh, E; Nicklas, JM; Lewis, BE (27 June 2000). "Acute endothelin A receptor blockade causes selective pulmonary vasodilation in patients with chronic heart failure". Circulation. 101 (25): 2922–7. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.101.25.2922. PMID 10869264.

- Hynynen, MM; Khalil, RA (January 2006). "The vascular endothelin system in hypertension--recent patents and discoveries". Recent Patents on Cardiovascular Drug Discovery. 1 (1): 95–108. doi:10.2174/157489006775244263. PMC 1351106. PMID 17200683.

- Weber, Cornelia; Schmitt, Rita; Birnboeck, Herbert; Hopfgartner, Gerard; van Marle, Sjoerd P.; Peeters, Pierre A.M.; Jonkman, Jan H.G.; Jones, Charles-Richard (August 1996). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the endothelin-receptor antagonist bosentan in healthy human subjects". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 60 (2): 124–137. doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90127-7. PMID 8823230.

- Jones, H. M.; Barton, H. A.; Lai, Y.; Bi, Y.-a.; Kimoto, E.; Kempshall, S.; Tate, S. C.; El-Kattan, A.; Houston, J. B.; Galetin, A.; Fenner, K. S. (16 February 2012). "Mechanistic Pharmacokinetic Modeling for the Prediction of Transporter-Mediated Disposition in Humans from Sandwich Culture Human Hepatocyte Data". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 40 (5): 1007–1017. doi:10.1124/dmd.111.042994. PMID 22344703.

- Treiber, A.; Schneiter, R.; Hausler, S.; Stieger, B. (30 April 2007). "Bosentan Is a Substrate of Human OATP1B1 and OATP1B3: Inhibition of Hepatic Uptake as the Common Mechanism of Its Interactions with Cyclosporin A, Rifampicin, and Sildenafil". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 35 (8): 1400–1407. doi:10.1124/dmd.106.013615. PMID 17496208.

- Weber, C; Gasser, R; Hopfgartner, G (July 1999). "Absorption, excretion, and metabolism of the endothelin receptor antagonist bosentan in healthy male subjects". Drug Metabolism and Disposition: The Biological Fate of Chemicals. 27 (7): 810–5. PMID 10383925.

- van Veldhuisen, Dirk J.; Poole-Wilson, Philip A. (August 2001). "The underreporting of results and possible mechanisms of 'negative' drug trials in patients with chronic heart failure". International Journal of Cardiology. 80 (1): 19–27. doi:10.1016/S0167-5273(01)00447-8. PMID 11532543.

- Helfand, Carly (2015). "The top 10 patent losses of 2015: Tracleer". FiercePharma.