Bone tumor

A bone tumor is a neoplastic growth of tissue in bone. Abnormal growths found in the bone can be either benign (noncancerous) or malignant (cancerous).

| Bone cancer | |

|---|---|

| |

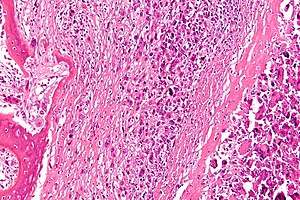

| Micrograph of an osteosarcoma, a malignant primary bone tumor. | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

Average five-year survival in the United States after being diagnosed with bone and joint cancer is 67%.[1]

Symptoms

The most common symptom of bone tumors is pain, which will gradually increase over time. A person may go weeks, months, and sometimes years before seeking help; the pain increases with the growth of the tumor. Additional symptoms may include fatigue, fever, weight loss, anemia, nausea, and unexplained bone fractures. Many patients will not experience any symptoms, except for a painless mass. Some bone tumors may weaken the structure of the bone, causing pathologic fractures.[2]

Types

Bone tumors may be classified as "primary tumors", which originate in bone or from bone-derived cells and tissues, and "secondary tumors" which originate in other sites and spread (metastasize) to the skeleton. Carcinomas of the prostate, breasts, lungs, thyroid, and kidneys are the carcinomas that most commonly metastasize to bone. Secondary malignant bone tumors are estimated to be 50 to 100 times as common as primary bone cancers.

Primary bone tumors

Primary tumors of bone can be divided into benign tumors and cancers. Common benign bone tumors may be neoplastic, developmental, traumatic, infectious, or inflammatory in etiology. Some benign tumors are not true neoplasms, but rather, represent hamartomas, namely the osteochondroma. The most common locations for many primary tumors, both benign and malignant include the distal femur and proximal tibia (around the knee joint).

Examples of benign bone tumors include osteoma, osteoid osteoma, osteochondroma, osteoblastoma, enchondroma, giant cell tumor of bone and aneurysmal bone cyst.

Malignant primary bone tumors include osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing's sarcoma, fibrosarcoma, and other types.

While malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) - now generally called "pleomorphic undifferentiated sarcoma" - primary in bone is known to occur occasionally,[3] current paradigms tend to consider MFH a "wastebasket" diagnosis, and the current trend is toward using specialized studies (i.e. genetic and immunohistochemical tests) to classify these undifferentiated tumors into other tumor classes. Multiple myeloma is a hematologic cancer, originating in the bone marrow, which also frequently presents as one or more bone lesions.

Germ cell tumors, including teratoma, often present and originate in the midline of the sacrum, coccyx, or both. These sacrococcygeal teratomas are often relatively amenable to treatment.

Secondary bone tumors

Since, by definition, benign bone tumors do not metastasize, all secondary bone tumors are metastatic lesions which have spread from other organs, most commonly carcinomas of the breast, lung, and prostate.

Reliable and valid statistics on the incidence, prevalence, and mortality of malignant bone tumors are difficult to come by, particularly in the oldest (those over 75 years of age), because carcinomas that are widely metastatic to bone are rarely ever curable, biopsies to determine the origin of the tumor in cases like this are rarely done.

Diagnosis

Projectional radiography ("X-ray") is the optimal initial imaging modality for evaluating undiagnosed primary bone tumors.[4] CT scan, MRI and/or histopathology can aid in reaching a final diagnosis, as well as staging thereof.

Staging

Stage 1A bone cancer

Stage 1A bone cancer Stage 1B bone cancer

Stage 1B bone cancer Stage 2A bone cancer

Stage 2A bone cancer Stage 2B bone cancer

Stage 2B bone cancer Stage 3 bone cancer

Stage 3 bone cancer

Treatment

Treatment of bone tumors is highly dependent on the type of tumor.

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are effective in some tumors (such as Ewing's sarcoma) but less so in others (such as chondrosarcoma).[5] There is a variety of chemotherapy treatment protocols for bone tumors. The protocol with the best reported survival in children and adults is an intra-arterial protocol where tumor response is tracked by serial arteriogram. When tumor response has reached >90% necrosis surgical intervention is planned.[6][7]

Medication

One of the major concerns is bone density and bone loss. Non-hormonal bisphosphonates increase bone strength and are available as once-a-week prescription pills. Metastron also known as strontium-89 chloride is an intravenous medication given to help with the pain and can be given in three month intervals. Generic Strontium Chloride Sr-89 Injection UPS, manufactured by Bio-Nucleonics Inc., it is the generic version of Metastron.[8]

Surgical treatment

Treatment for some bone cancers may involve surgery, such as limb amputation, or limb sparing surgery (often in combination with chemotherapy and radiation therapy). Limb sparing surgery, or limb salvage surgery, means the limb is spared from amputation. Instead of amputation, the affected bone is removed and replaced in one of two ways: (a) bone graft, in which bone is taken from elsewhere on the body or (b) artificial bone is put in. In upper leg surgeries, limb salvage prostheses are available.

The other surgery is called Van Nes rotation or rotationplasty which is a form of amputation, in which the patient's foot is turned upwards in a 180 degree turn and the upturned foot is used as a knee.

Types of amputation:

- Leg

- Below knee

- Above knee

- Symes

- Hip disarticulation

- Hemipelvectomy or hindquarter, in which the whole leg is removed with one half of the pelvis

- Arm

- Below elbow

- Above elbow

- Shoulder disarticulation

- Forequarter (amputation of the whole arm, along with the shoulder blade and the clavicle)

The most radical of amputations is hemicorporectomy (translumbar or waist amputation) which removes the legs, the pelvis, urinary system, excretory system and the genital area (penis/testes in males and vagina/vulva in females). This operation is done in two stages. First stage is doing the colostomy and the urinary conduit, the second stage is the amputation. This is a mutilating operation and is only done as a last resort (e.g. when even pelvic exenteration does not work or in cases of advanced pelvic/reproductive cancers)

Thermal ablation techniques

Over the past two decades, CT guided radiofrequency ablation has emerged as a less invasive alternative to surgical resection in the care of benign bone tumors, most notably osteoid osteomas. In this technique, which can be performed under conscious sedation, a RF probe is introduced into the tumor nidus through a cannulated needle under CT guidance and heat is applied locally to destroy tumor cells. Since the procedure was first introduced for the treatment of osteoid osteomas in the early 1990s,[9] it has been shown in numerous studies to be less invasive and expensive, to result in less bone destruction and to have equivalent safety and efficacy to surgical techniques, with 66 to 96% of patients reporting freedom from symptoms.[10][11][12] While initial success rates with RFA are high, symptom recurrence after RFA treatment has been reported, with some studies demonstrating a recurrence rate similar to that of surgical treatment.[13]

Thermal ablation techniques are also increasingly being used in the palliative treatment of painful metastatic bone disease. Currently, external beam radiation therapy is the standard of care for patients with localized bone pain due to metastatic disease. Although the majority of patients experience complete or partial relief of pain following radiation therapy, the effect is not immediate and has been shown in some studies to be transient in more than half of patients.[14] For patients who are not eligible or do not respond to traditional therapies ( i.e. radiation therapy, chemotherapy, palliative surgery, bisphosphonates or analgesic medications), thermal ablation techniques have been explored as alternatives for pain reduction. Several multi-center clinical trials studying the efficacy of RFA in the treatment of moderate to severe pain in patients with metastatic bone disease have shown significant decreases in patient reported pain after treatment.[15][16] These studies are limited however to patients with one or two metastatic sites; pain from multiple tumors can be difficult to localize for directed therapy. More recently, cryoablation has also been explored as a potentially effective alternative as the area of destruction created by this technique can be monitored more effectively by CT than RFA, a potential advantage when treating tumors adjacent to critical structures.[17]

Prognosis

The outlook depends on the type of tumor. The outcome is expected to be good for people with noncancerous (benign) tumors, although some types of benign tumors may eventually become cancerous (malignant). With malignant bone tumors that have not spread, most patients achieve a cure, but the cure rate depends on the type of cancer, location, size, and other factors.

See also

References

- "SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Bone and Joint Cancer". NCI. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- "Questions and Answers about Bone Cancer" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- Jeon DG, Song WS, Kong CB, Kim JR, Lee SY. MFH of Bone and Osteosarcoma Show Similar Survival and Chemosensitivity. Clin Orthop Rel Res 469;584-90.

- Costelloe, Colleen M.; Madewell, John E. (2013). "Radiography in the Initial Diagnosis of Primary Bone Tumors". American Journal of Roentgenology. 200 (1): 3–7. doi:10.2214/AJR.12.8488. ISSN 0361-803X.

- Bone tumor at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York

- 10 year survival in Pediatric Osteosarcoma

- Survival in Adult Osteosarcoma and MFH of Bone

- "FDA ANDA Generic Drug Approvals". Food and Drug Administration.

- Rosenthal, D I; Alexander, A; Rosenberg, A E; Springfield, D (1992-04-01). "Ablation of osteoid osteomas with a percutaneously placed electrode: a new procedure". Radiology. 183 (1): 29–33. doi:10.1148/radiology.183.1.1549690. ISSN 0033-8419. PMID 1549690.

- Rimondi, Eugenio; Mavrogenis, Andreas F.; Rossi, Giuseppe; Ciminari, Rosanna; Malaguti, Cristina; Tranfaglia, Cristina; Vanel, Daniel; Ruggieri, Pietro (2011-08-14). "Radiofrequency ablation for non-spinal osteoid osteomas in 557 patients". European Radiology. 22 (1): 181–188. doi:10.1007/s00330-011-2240-1. ISSN 0938-7994. PMID 21842430.

- Rosenthal, Daniel I.; Hornicek, Francis J.; Torriani, Martin; Gebhardt, Mark C.; Mankin, Henry J. (2003-10-01). "Osteoid Osteoma: Percutaneous Treatment with Radiofrequency Energy". Radiology. 229 (1): 171–175. doi:10.1148/radiol.2291021053. ISSN 0033-8419. PMID 12944597.

- Weber, Marc-André; Sprengel, Simon David; Omlor, Georg W.; Lehner, Burkhard; Wiedenhöfer, Bernd; Kauczor, Hans-Ulrich; Rehnitz, Christoph (2015-04-25). "Clinical long-term outcome, technical success, and cost analysis of radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of osteoblastomas and spinal osteoid osteomas in comparison to open surgical resection". Skeletal Radiology. 44 (7): 981–993. doi:10.1007/s00256-015-2139-z. ISSN 0364-2348. PMID 25910709.

- Rosenthal, Daniel I.; Hornicek, Francis J.; Wolfe, Michael W.; Jennings, L. Candace; Gebhardt, Mark C.; Mankin, Henry J. (1998-06-01). "Percutaneous Radiofrequency Coagulation of Osteoid Osteoma Compared with Operative Treatment*". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 80 (6): 815–21. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1018.5024. doi:10.2106/00004623-199806000-00005. ISSN 0021-9355. PMID 9655099. Archived from the original on 2016-10-06. Retrieved 2016-08-07.

- Tong, Daphne; Gillick, Laurence; Hendrickson, Frank R. (1982-09-01). "The palliation of symptomatic osseous metastases final results of the study by the radiation therapy oncology group". doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19820901)50:5<893::aid-cncr2820500515>3.0.co;2-y. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dupuy, Damian E.; Liu, Dawei; Hartfeil, Donna; Hanna, Lucy; Blume, Jeffrey D.; Ahrar, Kamran; Lopez, Robert; Safran, Howard; DiPetrillo, Thomas (2010-02-15). "Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of painful osseous metastases". Cancer. 116 (4): 989–997. doi:10.1002/cncr.24837. ISSN 1097-0142. PMC 2819592. PMID 20041484.

- Goetz, Matthew P.; Callstrom, Matthew R.; Charboneau, J. William; Farrell, Michael A.; Maus, Timothy P.; Welch, Timothy J.; Wong, Gilbert Y.; Sloan, Jeff A.; Novotny, Paul J. (2004-01-15). "Percutaneous Image-Guided Radiofrequency Ablation of Painful Metastases Involving Bone: A Multicenter Study". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 22 (2): 300–306. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.03.097. ISSN 0732-183X. PMID 14722039.

- Callstrom, Matthew R.; Dupuy, Damian E.; Solomon, Stephen B.; Beres, Robert A.; Littrup, Peter J.; Davis, Kirkland W.; Paz-Fumagalli, Ricardo; Hoffman, Cheryl; Atwell, Thomas D. (2013-03-01). "Percutaneous image-guided cryoablation of painful metastases involving bone". Cancer. 119 (5): 1033–1041. doi:10.1002/cncr.27793. ISSN 1097-0142. PMC 5757505. PMID 23065947.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |