Binswanger's disease

Binswanger's disease, also known as subcortical leukoencephalopathy and subcortical arteriosclerotic encephalopathy (SAE), is a form of small vessel vascular dementia caused by damage to the white brain matter.[1] White matter atrophy can be caused by many circumstances including chronic hypertension as well as old age.[2] This disease is characterized by loss of memory and intellectual function and by changes in mood. These changes encompass what are known as executive functions of the brain.[3] It usually presents between 54 and 66 years of age, and the first symptoms are usually mental deterioration or stroke.[4]

| Binswanger's disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Subcortical arteriosclerotic encephalopathy |

| |

| Specialty | Neurology |

It was described by Otto Binswanger in 1894, and[5] Alois Alzheimer first used the phrase "Binswanger's disease" in 1902.[6] However, Olszewski is credited with much of the modern-day investigation of this disease which began in 1962.[4][7]

Symptoms

Symptoms include mental deterioration, language disorder, transient ischemic attack, muscle ataxia, and impaired movements including change of walk, slowness of movements, and change in posture. These symptoms usually coincide with multiple falls, epilepsy, fainting, and uncontrollable bladder.[4]

Because Binswanger's disease affects flow processing speed and causes impaired concentration, the ability to do everyday tasks such as managing finances, preparing a meal and driving may become very difficult.[2]

Neural presentation

Binswanger's disease is a type of subcortical vascular dementia caused by white matter atrophy to the brain. However, white matter atrophy alone is not sufficient for this disease; evidence of subcortical dementia is also necessary.[8]

The histologic findings are diffuse, irregular loss of axons and myelin accompanied by widespread gliosis, tissue death due to an infarction or loss of blood supply to the brain, and changes in the plasticity of the arteries. The pathologic mechanism may be damage caused by severe atherosclerosis. The onset of this disease is typically between 54 – 66 years of age and the first symptoms are usually mental deterioration or stroke.[3]

The vessels that supply the subcortical white matter come from the vessels that support basal ganglia, internal capsule, and thalamus. It is described as its own zone by and susceptible to injury. Chronic hypertension is known to cause changes in the tension of the smooth wall vessels and changes in the vessel diameter.[2] Arterioles can become permeable resulting in compromise of the blood brain barrier.[3][9] It has been shown that Binswanger's disease targets the vessels in this zone of the subcortex, but spares the microcirculation's vessels and capillaries which may be attributed to a difference between Alzheimer's and Binswanger's disease.[10]

Mental presentation

There is a difference between cortical and subcortical dementia. Cortical dementia is atrophy of the cortex which affects ‘higher’ functions such as memory, language, and semantic knowledge whereas subcortical dementia affects mental manipulation, forgetfulness, and personality/emotional changes. Binswanger's Disease has shown correlations with impairment in executive functions, but have normal episodic or declarative memory. Executive functions are brain processes that are responsible for planning, cognitive flexibility, abstract thinking, rule acquisition, initiating appropriate actions and inhibiting inappropriate actions, and selecting relevant sensory information. There have been many studies done comparing the mental deterioration of Binswanger patients and Alzheimer patients. It has been found in the Graphical Sequence Test that Binswanger patients have hyperkinetic perseveration errors which cause the patients to repeat motion even when not asked whereas Alzheimer patients have semantic perseveration because when asked to write a word they will instead draw an image depicting the word.[11]

Diagnosis

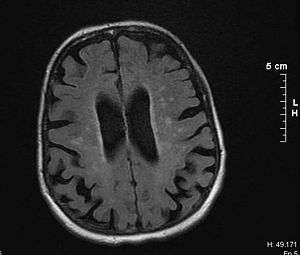

Binswanger's disease can usually be diagnosed with a CT scan, MRI, and a proton MR spectrography in addition to clinical examination. Indications include infarctions, lesions, or loss of intensity of central white matter and enlargement of ventricles, and leukoaraiosis. A Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE) has been created to quickly assess cognitive impairment and serves as a screening test for dementia across different cultures.

Imaging

Leukoaraiosis (LA) refers to the imaging finding of white matter changes that are common in Binswanger disease. However, LA can be found in many different diseases and even in normal patients, especially in people older than 65 years of age.[4]

There is controversy whether LA and mental deterioration actually have a cause and effect relationship. Recent research is showing that different types of LA can affect the brain differently, and that proton MR spectroscopy would be able to distinguish the different types more effectively and better diagnosis and treat the issue.[8] Because of this information, white matter changes indicated by an MRI or CT cannot alone diagnose Binswanger disease, but can aid to a bigger picture in the diagnosis process. There are many diseases similar to Binswanger's disease including CADASIL syndrome and Alzheimer's disease, which makes this specific type of white matter damage hard to diagnose.[4] Binswanger disease is best when diagnosed of a team by experts including a neurologist and psychiatrist to rule out other psychological or neurological problems.[2] Because doctors must successfully detect enough white matter alterations to accompany dementia as well as an appropriate level of dementia, two separate technological systems are needed in the diagnosing process.

Much of the major research today is done on finding better and more efficient ways to diagnose this disease. Many researchers have divided the MRIs of the brain into different sections or quadrants. A score is given to each section depending on how severe the white matter atrophy or leukoaraiosis is. Research has shown that the higher these scores, the more of a decrease in processing speed, executive functions, and motor learning tasks.[12][13] Other researchers have begun using computers to calculate the percentage of white matter atrophy by counting the hyper-intense pixels of the MRI. These and similar reports show a correlation between the amount of white matter alterations and the decline of psychomotor functions, reduced performance on attention and executive control.[14][15] One recent type of technology is called susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) which is a magnetic resonance technique which has an unusually high degree of sensitivity and can better detect white matter alterations.[16]

Management

Binswanger's disease has no cure and has been shown to be the most severe impairment of all of the vascular dementias.[17] The best way to manage the vascular risk factors that contribute to poor perfusion in the brain is to treat the cause, such as chronic hypertension or diabetes. It has been shown that current Alzheimer's medication, donepezil (trade name Aricept), may help Binswanger's Disease patients as well . Donepezil increases the acetylcholine in the brain through a choline esterase inhibitor which deactivates the enzyme that breaks down acetylcholine.[2] Alzheimer as well as Binswanger patients have low levels of acetylcholine and this helps to restore the normal levels of neurotransmitters in the brain.[2] This drug may improve memory, awareness, and the ability to function.[18] If no medical interception of the disease is performed then the disease will continue to worsen as the patient ages due to the continuing atrophy of the white matter from whatever was its original cause.[2]

History

Binswanger in 1894 was the first to claim that white matter atrophy caused by 'vascular insufficiency' can result in dementia. He described a patient who had slow progression of dementia as well as subcortical white matter atrophy, ventricle enlargement, aphasia, hemianopsia, and hemiparesis.[8] He named this disease 'encenphailitis subcorticalis chronica progressive.' Binswanger did not conduct any microscopic investigations so many did not believe his findings and attributed the neural damage to neural syphilis.[2] Alzheimer in 1902 studied Binswanger's work with pathological evidence that concluded and supported Binswanger's ideas and hypotheses. Alzheimer renamed this disease Binswanger's disease.[3]

In the late 19th century vascular dementia was heavily studied, however by 1910 scientists were lumping Binswanger's disease with all other subcortical and cortical dementia and labeling everything senile dementia despite all previous research and efforts to distinguish this disease from the rest. In 1962 J. Olszewski published an extensive review of all literature about Binswanger's disease so far. He discovered that some of the information in the original reports was incorrect and that at least some of the patients studied in these cases probably had neurosyphilis or other types of dementia. Even with these errors, Olszewski concluded that Binswanger disease did exist as a subset of cerebral arteriosclerosis.[17] Yet again, in 1974 the term multi-infarct dementia was coined and all vascular dementia was grouped into one category. Because of this, the specific names of these types of this dementia, including Binswanger's disease were lost.[3] This was until 1992 when Alzheimer's diagnostic centers created specific criteria known as the Hachinski Ischemic Scale (after Dr. Vladimir Hachinski) which became the standard for diagnosing MID or vascular dementia.[19]

The complicated history of Binswanger's disease and the fact that it was overlooked as a disease for many years means many patients may have been misdiagnosed with Alzheimer's disease.[8]

References

- Akiguchi I, Tomimoto H, Suenaga T, Wakita H, Budka H (1997). "Alterations in glia and axons in the brains of Binswanger's disease patients". Stroke. 28 (7): 1423–9. doi:10.1161/01.str.28.7.1423. PMID 9227695. Archived from the original on 2013-01-12.

- Giovannetti, T. Personal Interview. 16 October 2009

- Libon, David; Price, C.; Davis Garrett, K.; T. Giovannetti (2004). "From Binswanger's Disease to Leukoaraiosis: What We Have Learned About Subcortical Vascular Dementia". The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 18 (1): 83–100. doi:10.1080/13854040490507181. PMID 15595361.

- Loeb C (2000). "Binswanger's disease is not a single entity". Neurol. Sci. 21 (6): 343–8. doi:10.1007/s100720070048. PMID 11441570. Archived from the original on 2013-01-04.

- Pantoni L, Moretti M, Inzitari D (1996). "The first Italian report on "Binswanger's disease"". Ital J Neurol Sci. 17 (5): 367–70. doi:10.1007/BF01999900. PMID 8933231.

- "Review: Binswanger's disease, leuokoaraiosis and dementia". Age and Ageing. 1994. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- Olszewski J (1962). "Subcortical arteriosclerotic encephalopathy. Review of the literature on the so-called Binswanger's disease and presentation of two cases". World Neurol. 3: 359–75. PMID 14481961.

- Libon, D., Scanlon, M., Swenson, R., and H. Branch Coslet(1990): "Binswanger's disease: some Neuropsychological Considerations", Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 3(1):31-40.

- de Reuck, J. (1971). "The human periventricular arterial blood supply and anatomy of cerebral infarctions". European Neurology. 5 (6): 321–334. doi:10.1159/000114088. PMID 5141149.

- Kitaguchi, Hiroshi; Ihara, M.; Saiki, H.; Takahashi, R.; H. Tomimoto (1 May 2007). "Capillary beds are decreased in Alzheimer's disease, but not in Binswanger's disease". Neuroscience Letters. 417 (2): 128–131. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.021. PMID 17403574.

- Goldberg, E. (1986): “Varieties of perseveration: A comparison of two taxonomies.”, Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 8:710-726.

- Junque, C.; Pujol, J.; Vendrell, P.; Bruna, O.; Jodar, M.; Ribas, J.C.; Vinas, J.; Capevila, A.; Marti-Wilalta, J.L. (1990). "Leukoaraiosis on magnetic resonance imaging and speed of mental processing". Archives of Neurology. 47 (2): 151–156. doi:10.1001/archneur.1990.00530020047013. PMID 2302086.

- Libon, David; Bogdanoff, B.; Cloud, B.S.; Skalina, S.; Carew, T.G.; Gitlin, H.L.; Bonavita, J. (1998). "Motor Learning and quantitative measures of the hippocampus and subcortical white alterations in Alzheimer's disease and Ischaemic Vascular Dementia". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 20 (1): 30–41. doi:10.1076/jcen.20.1.30.1490. PMID 9672817.

- Davis-Garrett, K.L.; Cohen, R.A.; Paul, R.H.; Moser, D.J.; Malloy, P.F.; Shah, P. (2004). "Computer-mediated measurement and subjective ratings of white matter hyperintensities in vascular dementia: Relationships to neuropsychological performance. I". The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 18 (1): 50–62. doi:10.1080/13854040490507154. PMID 15595358.

- Moser, D.J.; Cohen, R.A.; Paul, R.H.; Paulsen, J.S.; Ott, B.R.; Gordon, N.M.; Bell, S.; Stone, W.M. (2001). "Executive function and magnetic resonance imaging subcortical hyperintensities in Vascular dementia". Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology & Behavioral Neurology. 14: 89–92.

- Santhosh, K.; Kesavadas, C.; Thomas, B.; Gupta, A.K.; Thamburaj, K.; T. Raman Kapilamoorthy (January 2009). "Susceptibility weighted imaging: a new tool in magnet resonance imaging of stroke". Clinical Radiology. 64 (1): 74–83. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2008.04.022. PMID 19070701.

- Thajeb, Peterus; Thajeb, T.; and D. Dai (March 2007). "Cross-cultural studies using a modified mini mental test for healthy subjects and patients with various forms of vascular dementia". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 14 (3): 236–241. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2005.12.032. PMID 17258132.

- "Aricept". Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- Hachinski, V.C., Iliff, L.D., Zilhka, E., Du Boulay, G.H., McAllister, V.L., Marshall, J., Russell, R.W.R., and Symon, L. (1975): “Cerebral blood flow in dementia”, Archives of Neurology, 32:632-7.