Basilar membrane

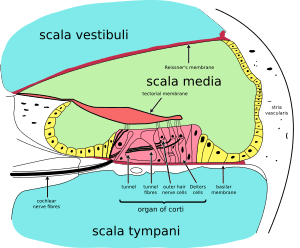

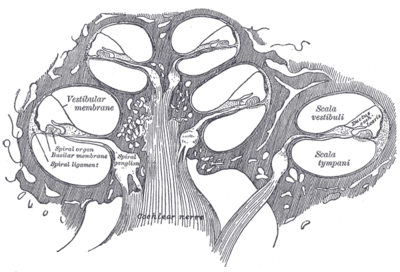

The basilar membrane is a stiff structural element within the cochlea of the inner ear which separates two liquid-filled tubes that run along the coil of the cochlea, the scala media and the scala tympani. The basilar membrane moves up and down in response to incoming sound waves, which are converted to traveling waves on the basilar membrane.

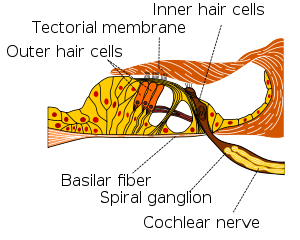

| Basilar membrane. | |

|---|---|

Section through organ of corti, showing basilar membrane | |

Cross section of the cochlea. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | membrana basilaris ductus cochlearis |

| MeSH | D001489 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

The basilar membrane is a pseudo-resonant structure[1] that, like the strings on an instrument, varies in width and stiffness. But unlike the parallel strings of a guitar, the basilar membrane is a single structure with different width, stiffness, mass, damping, and duct dimensions at different points along its length. The motion of the basilar membrane is generally described as a traveling wave.[2] The properties of the membrane at a given point along its length determine its characteristic frequency (CF), the frequency at which it is most sensitive to sound vibrations. The basilar membrane is widest (0.42–0.65 mm) and least stiff at the apex of the cochlea, and narrowest (0.08–0.16 mm) and stiffest at the base (near the round and oval windows).[3] High-frequency sounds localize near the base of the cochlea, while low-frequency sounds localize near the apex.

Function

Endolymph/perilymph separation

Along with the vestibular membrane, several tissues held by the basilar membrane segregate the fluids of the endolymph and perilymph, such as the inner and outer sulcus cells (shown in yellow) and the reticular lamina of the organ of Corti (shown in magenta). For the organ of Corti, the basilar membrane is permeable to perilymph. Here the border between endolymph and perilymph occurs at the reticular lamina, the endolymph side of the organ of Corti.[6]

A base for the sensory cells

The basilar membrane is also the base for the hair cells. This function is present in all land vertebrates. Due to its location, the basilar membrane places the hair cells adjacent to both the endolymph and the perilymph, which is a precondition of hair cell function.

Frequency dispersion

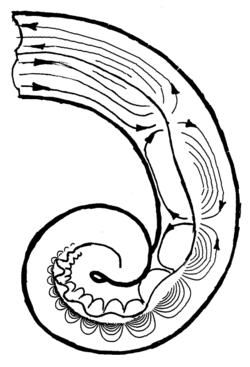

A third, evolutionarily younger, function of the basilar membrane is strongly developed in the cochlea of most mammalian species and weakly developed in some bird species:[7] the dispersion of incoming sound waves to separate frequencies spatially. In brief, the membrane is tapered and it is stiffer at one end than at the other. Furthermore, sound waves travelling to the "floppier" end of the basilar membrane have to travel through a longer fluid column than sound waves travelling to the nearer, stiffer end. Each part of the basilar membrane, together with the surrounding fluid, can therefore be thought of as a "mass-spring" system with different resonant properties: high stiffness and low mass, hence high resonant frequencies at the near (base) end, and low stiffness and high mass, hence low resonant frequencies, at the far (apex) end.[8] This causes sound input of a certain frequency to vibrate some locations of the membrane more than other locations. The distribution of frequencies to places is called the tonotopic organization of cochlea.

Sound-driven vibrations travel as waves along this membrane, along which, in humans, lie about 3,500 inner hair cells spaced in a single row. Each cell is attached to a tiny triangular frame. The 'hairs' are minute processes on the end of the cell, which are very sensitive to movement. When the vibration of the membrane rocks the triangular frames, the hairs on the cells are repeatedly displaced, and that produces streams of corresponding pulses in the nerve fibers, which are transmitted to the auditory pathway.[9] The outer hair cells feed back energy to amplify the traveling wave, by up to 65 dB at some locations.[10][11] In the membrane of the outer hair cells there are motor proteins associated with the membrane. Those proteins are activated by sound-induced receptor potentials as the basilar membrane moves up and down. These motor proteins can amplify the movement, causing the basilar membrane to move a little bit more, amplifying the traveling wave. Consequently, the inner hair cells get more displacement of their cilia and move a little bit more and get more information than they would in a passive cochlea.

Generating receptor potential

The movement of the basilar membrane causes hair cell stereocilia movement. The hair cells are attached to the basilar membrane, and with the moving of the basilar membrane, the tectorial membrane and the hair cells are also moving, with the stereocilia bending with the relative motion of the tectorial membrane. This can cause opening and closing of the mechanically gated potassium channels on the cilia of the hair cell. The cilia of the hair cell are in the endolymph. Unlike the normal cellular solution, low concentration of potassium and high of sodium, the endolymph is high concentration of potassium and low of sodium. And it is isolated, which means it does not have a resting potential of −70mV comparing with other normal cells, but rather maintains a potential about +80mV. However, the base of the hair cell is in the perilymph, with a 0 mV potential. This leads to the hair cell have a resting potential of -45 mV. As the basilar membrane moves upward, the cilia move in the direction causing opening of the mechanically gated potassium channel. The influx of potassium ions leads to depolarization. On the contrary, the cilia move the other way as the basilar membrane moves down, closing more mechanically gated potassium channels and leading to hyperpolarization. Depolarization will open the voltage gated calcium channel, releasing neurotransmitter (glutamate) at the nerve ending, acting on the spiral ganglion cell, the primary auditory neurons, making them more likely to spike. Hyperpolarization causes less calcium influx, thus less neurotransmitter release, and a reduced probability of spiral ganglion cell spiking.

Additional images

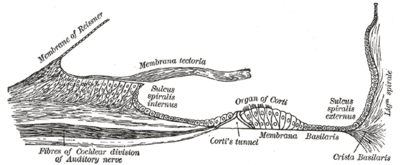

Diagrammatic longitudinal section of the cochlea.

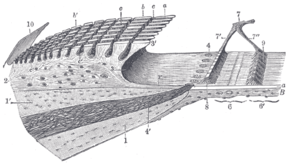

Diagrammatic longitudinal section of the cochlea. Floor of cochlear duct.

Floor of cochlear duct. Spiral limbus and basilar membrane.

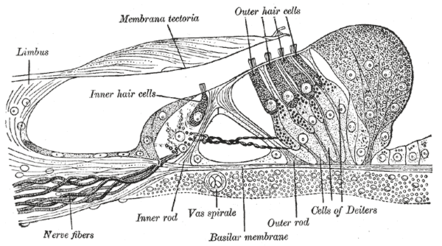

Spiral limbus and basilar membrane. Section through the spiral organ of Corti (magnified)

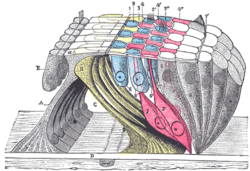

Section through the spiral organ of Corti (magnified) The reticular membrane and subjacent structures.

The reticular membrane and subjacent structures.

See also

References

- M. Holmes and J. D. Cole, "Pseudoresonance in the cochlea, ' in: Mechanics of Hearing, E. de Boer and M. A. Viergever (editors), Proceedings of the IUTAM/ICA Symposium, Delft (1983), pp. 45-52.

- Richard R. Fay; Arthur N. Popper & Sid P. Bacon (2004). Compression: From Cochlea to Cochlear Implants. Springer. ISBN 0-387-00496-3.

- Oghalai JS. The cochlear amplifier: augmentation of the traveling wave within the inner ear. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head & Neck Surgery. 12(5):431-8, 2004

- Shera, Christopher A. (2007). "Laser amplification with a twist: Traveling-wave propagation and gain functions from throughout the cochlea". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 122 (5): 2738–2758. doi:10.1121/1.2783205. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- Robles, L.; Ruggero, M. A. (2001). "Mechanics of the mammalian cochlea". Physiological Reviews. 81 (3): 1305–1352. PMC 3590856. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- Salt, A.N., Konishi, T., 1986. The cochlear fluids: Perilymph and endolymph. In: Altschuler, R.A., Hoffman, D.W., Bobbin, R.P. (Eds.), Neurobiology of Hearing: The Cochlea. Raven Press, New York, pp. 109-122

- Fritzsch B: The water-to-land transition: Evolution of the tetrapod basilar papilla; middle ear, and auditory nuclei. In: Douglas B. Webster; Richard R. Fay; Arthur N. Popper, eds. (1992). The Evolutionary biology of hearing. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 351–375. ISBN 0-387-97588-8.

- Schnupp J.; Nelken I.; King A. (2011). Auditory Neuroscience. Cambridge MA: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-11318-X.

-

Beament, James (2001). "How We Hear Music: the Relationship Between Music and the Hearing Mechanism". Woodbridge: Boydell Press: 97. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - K E Nilsen and I J R (1999). "Timing of cochlear feedback: spatial and temporal representation of a tone across the basilar membrane". Nature Neuroscience. 2 (7): 642–648. doi:10.1038/10197. PMID 10404197. Vancouver style error: punctuation (help)

- K E Nilsen and I J R (2000). "The spatial and temporal representation of a tone on the guinea pig basilar membrane". Proceedings of the National Academy of Science U.S.A. 97 (22): 11751–11758. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.22.11751. PMC 34345. PMID 11050205. Vancouver style error: punctuation (help)

External links

- Auditory Neuroscience | The Ear several animations showing basilar membrane motion under various stimulus conditions

- Functional anatomy of the inner ear: plenty of images, animations, and very concise functional explanations

- Basilar Membrane Simulator Video and Scripts to Simulate the Basilar Membrane

- The role of the basilar membrane in sound reception: good explanation and diagrams