Barber surgeon

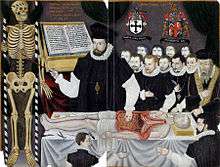

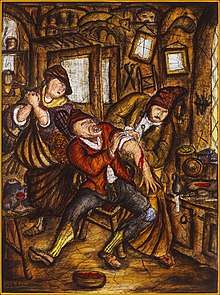

The barber surgeon, one of the most common European medical practitioners of the Middle Ages, was generally charged with caring for soldiers during and after battle. In this era, surgery was seldom conducted by physicians, but instead by barbers, who, possessing razors and coordination indispensable to their trade, were called upon for numerous tasks ranging from cutting hair to amputating limbs.

In this period surgical mortality was very high, due to blood loss and infection. Yet since doctors thought that blood letting treated illness, barbers also applied leeches. Meanwhile, physicians considered themselves to be above surgery.[1] Physicians mostly observed surgical patients and offered consulting, but otherwise often chose academia, working in universities, or chose residence in castles where they treated the wealthy.

Middle Ages in Europe

Due to religious and sanitary monastic regulations, monks had to maintain their tonsure (the traditional baldness on the top of the head of Catholic monks). This created a market for barbers, because each monastery had to train or hire a barber. They would perform bloodletting and other minor surgeries like pulling teeth or creating ointments. The first barber surgeons to be recognized as such worked in monasteries around 1000 A.D.[1]

Because physicians performed surgery so rarely, the Middle Ages saw a proliferation of barbers, among other medical "paraprofessionals", including cataract couchers, herniotomists, lithotomists, midwives, and pig gelders. In 1254, Bruno di Longoburgo, a physician who wrote on surgery, was concerned about barbers performing phlebotomies and scarifications.[1]

Barbers in Paris and Italy

In Paris, disputes between doctors led to the widespread patronage of barbers. The College of St. Cosme had two levels of student doctors: doctors who were given a long academic robe were permitted to perform surgeries and doctors who were given a short robe and had to pass a special examination before being given that license. The short-robed doctors were bitter because the long-robed physicians behaved pretentiously.

The short-robed doctors of St. Cosme entered into an agreement with the barber surgeons of Paris that they would offer the barber surgeons secret lessons on human anatomy as long as they swore to be dependents and supporters of the short-robed physicians. This secret deal existed from around the time of the founding of St. Cosme in 1210 until 1499, when the group of surgeon barbers asked for their own cadaver to perform their anatomical demonstrations. In 1660, the barber surgeons eventually recognized the physicians' dominance.[1]

In Italy, barbers were not as common. The Salerno medical school trained physicians to be competent surgeons, as did the schools in Bologna and Padua. In Florence, physicians and surgeons were separated, but the Florentine Statute concerning the Art of Physicians and Pharmacists in 1349 gave barbers an inferior legal status compared to surgeons.[1]

Barbers in the British Isles in the Early Modern Period

Formal recognition of their skills (in England at least) goes back to 1540,[2] when the Fellowship of Surgeons (who existed as a distinct profession but were not "Doctors/Physicians" for reasons including that, as a trade, they were trained by apprenticeship rather than academically) merged with the Company of Barbers, a London livery company, to form the Company of Barber-Surgeons. However, the trade was gradually put under pressure by the medical profession and in 1745, the surgeons split from the Barbers' Company (which still exists) to form the Company of Surgeons. In 1800 a Royal Charter was granted to this company and the Royal College of Surgeons in London came into being (later it was renamed to cover all of England — equivalent colleges exist for Scotland and Ireland as well as many of the old UK colonies, e.g., Canada).[3]

Few traces of barbers' links with the surgical side of the medical profession remain. One is the traditional red and white barber's pole, or a modified instrument from a blacksmith, which is said to represent the blood and bandages associated with their older role. Another link is the British use of the title "Mr" rather than "Dr" by surgeons (when they become qualified as surgeons by, e.g., the award of an MRCS or FRCS diploma). This dates back to the days when surgeons did not have a university education (let alone a doctorate); this link with the past is retained despite the fact that all surgeons now have to gain a basic medical degree and doctorate (as well as undergoing several more years training in surgery). They no longer perform haircuts, a task the barbers have retained.

History

A barber surgeon was a person who could perform minor surgical procedures such as bloodletting, cupping therapy or pulling teeth. Barbers could also bathe, cut hair, shave or trim facial hair, and give enemas. The surgeon came with the army at war but could be used by individuals in peacetime.[4]

The surname 'Bader' comes from German and Jewish (Ashkenazic) origins and refers to the occupation of barber surgeon, barber, or one who tends a bath house.[5][6] The German verb 'baden' means to bathe, but when capitalized the surname 'Baden' is a geographical surname referring to the region of Baden-Württemberg in Germany.[7][8]

See also

- Feldsher

- Elinor Sneshell

- List of barbers

References

- McGrew, Roderick (1985). Encyclopedia of Medical History. New York: McGraw Hill. pp. 30–31. ISBN 0070450870.

- 32 Henry VIII c. 42

- Sven Med Tidskr. (2007). "From barber to surgeon- the process of professionalization". Svensk medicinhistorisk tidskrift. 11 (1): 69–87. PMID 18548946.

- "Upplandia.se -En webbplats om Uppland - Begrepp yrken & titlar". Upplandia.se. 10 February 2011. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- "The Origins and Meaning of Ashkenazic Last Names". www.jewishcurrents.org. Retrieved 2015-06-11.

- "Bader Name Meaning & Bader Family History at Ancestry.com". ancestry.com.

- "Surname Database: Baden Last Name Origin". The Internet Surname Database.

- "dict.cc - baden - Wörterbuch Englisch-Deutsch". dict.cc.

External links

![]()