Arsenic poisoning cases

Arsenic poisoning, accidental or deliberate, has been implicated in the illness and death of a number of prominent people throughout history.

- Francesco I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany

- Recent forensic evidence uncovered by Italian scientists suggests that Francesco (1541–1587) and his wife were poisoned, possibly by his brother and successor Ferdinando.[1]

- Eric XIV of Sweden

- Towards the end of his life, king Eric XIV (1533–1577) was held prisoner in many different castles in both Sweden and Finland. He died in prison in Örbyhus Castle: according to a tradition starting with Johannes Messenius, his final meal was a poisoned bowl of pea soup. A document signed by his brother, John III of Sweden, and a nobleman, Bengt Bengtsson Gylta (1514–74), gave Eric's guards in his last prison authorization to poison him if anyone tried to release him. His body was exhumed in 1958 and modern forensic analysis revealed evidence of lethal arsenic poisoning.[2][3]

- George III of Great Britain

- George III's (1738–1820) personal health was a concern throughout his long reign. He suffered from periodic episodes of physical and mental illness, five of them disabling enough to require the King to withdraw from his duties. In 1969, researchers asserted that the episodes of madness and other physical symptoms were characteristic of the disease porphyria, which was also identified in members of his immediate and extended family. In addition, a 2004 study of samples of the King's hair[4] revealed extremely high levels of arsenic, which is a possible trigger of disease symptoms. A 2005 article in the medical journal The Lancet[5] suggested the source of the arsenic could be the antimony used as a consistent element of the King's medical treatment. The two minerals are often found in the same ground, and mineral extraction at the time was not precise enough to eliminate arsenic from compounds containing antimony.

- Theodor Ursinus

- Theodor Gottlieb Ursinus (1749–1800),[6] a high-ranking Prussian civil servant and justice official, was poisoned by his wife Charlotte Ursinus (1760–1836). At the time, his death was ruled a stroke, but soon after the widow was found to have poisoned, between 1797 and 1801, not only her husband, but also her aunt and her lover, as well as to have attempted to poison her servant in 1803. Her sensational trial led to the first reliable method of identifying arsenic poisoning.[7]

- Napoleon Bonaparte

- It has been suggested that Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) suffered and died from arsenic poisoning during his imprisonment on the island of Saint Helena. Forensic samples of his hair did show high levels, 13 times the normal amount, of the element. This, however, does not prove deliberate poisoning by Napoleon's enemies: copper arsenite has been used as a pigment in some wallpapers, and microbiological liberation of the arsenic into the immediate environment would be possible. The case is equivocal in the absence of clearly authenticated samples of the wallpaper. Samples of hair taken during Napoleon's lifetime also show levels of arsenic, so that arsenic from the soil could not have polluted the post-mortem sample. Even without contaminated wallpaper or soil, commercial use of arsenic at the time provided many other routes by which Napoleon could have consumed enough arsenic to leave this forensic trace.[8]:226–228

- Simón Bolívar

- South American independence leader Simón Bolívar (1783–1830), according to Paul Auwaerter from the Division of Infectious Diseases in the Department of Medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, may have died due to chronic arsenic poisoning further complicated by bronchiectasis and lung cancer.[9][10] Auwaerter has considered murder and acute arsenic poisoning unlikely, arguing that gradual "environmental contact with arsenic would have been entirely possible" as a result of drinking contaminated water in Peru or through the medicinal use of arsenic (which was common at the time) as Bolívar had reportedly resorted to it during the treatment for some of his illnesses.[9]

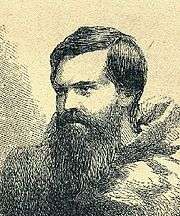

Charles Francis Hall

- Charles Francis Hall

- American explorer Charles Francis Hall (1821–1871) died unexpectedly during his third journey to the Arctic, the Polaris expedition. After returning to the ship from a sledging expedition Hall drank a cup of coffee and fell violently ill.[11]

- He collapsed in what was described as a fit. He suffered from vomiting and delirium for the next week, then seemed to improve for a few days. He accused several of the ship's company, including the ship's physician Emil Bessels—with whom he had longstanding disagreements—of having poisoned him.[11] Shortly thereafter, Hall again began suffering the same symptoms, died, and was taken ashore for burial. Following the expedition's return a U.S. Navy investigation ruled that Hall had died from apoplexy.[12]

- In 1968, however, Hall's biographer Chauncey C. Loomis, a professor at Dartmouth College, traveled to Greenland to exhume Hall's body. Due to the permafrost, Hall's body, flag shroud, clothing, and coffin were remarkably well preserved. Tissue samples of bone, fingernails, and hair showed that Hall died of poisoning from large doses of arsenic in the last two weeks of his life,[13] consistent with the symptoms party members reported. It is possible that he was murdered by Bessels or one of the other members of the expedition.

- Clare Boothe Luce

- Clare Boothe Luce (1903–1987), the American ambassador to Italy from 1953 to 1956, did not die from arsenic poisoning, but suffered an increasing variety of physical and psychological symptoms until arsenic was implicated. Its source was traced to the flaking arsenic-laden paint on the ceiling of her bedroom. She may also have eaten food contaminated by arsenic in flaking ceiling paint in the embassy dining room.[8]:356

- Guangxu Emperor

- In 2008, testing in the People's Republic of China confirmed that the Guangxu Emperor (1871–1908) was poisoned with a massive dose of arsenic; suspects include his dying aunt, Empress Dowager Cixi, and her strongman, Yuan Shikai.[14][15]

- Phar Lap

- The famous and largely successful New Zealand-bred racehorse Phar Lap died suddenly in 1932. Poisoning was considered as a cause of death and several forensic examinations were completed at the time of death. In a recent examination, 75 years after his death, forensic scientists determined that the horse had ingested a massive dose of arsenic shortly before his death.[16]

- King Faisal I of Iraq

- According to his British nurse, Lady Badget, King Faisal I of Iraq suffered from symptoms similar to those of arsenic poisoning during his last visit to Switzerland for treatment in 1933, at the age of 48. His Swiss doctors found him in a very healthy situation a day before.[17]

- Anderson Mazoka

- The popular opposition leader in Zambia, Anderson Mazoka, whose health deteriorated after the 2001 presidential elections, repeatedly accused government agents of poisoning him. His daughter, Mutinta, confirmed after his death on 24 May 2006 that arsenic was found in his body after he died from kidney complications.[18]

- Munir Said Thalib

- Munir Said Thalib, an Indonesian human right and anti-corruption activist, was poisoned with arsenic onboard Garuda Indonesia flight from Jakarta to Amsterdam on September 7, 2004. The Netherlands Forensic Institute revealed that Munir's body contained a level of arsenic almost three times the lethal dose. Pollycarpus Budihari Priyanto, an active pilot at the time of the assassination, was found guilty of murder. Despite the guilty verdict, the circumstances surrounding the case remained unclear.[19]

- Emmerson Mnangagwa

- Robert Mugabe's successor as President of Zimbabwe, Emmerson Mnangagwa has claimed he was poisoned with arsenic at a rally. His entourage has suggested that supporters of Grace Mugabe were responsible.[20]

- Moriku Joyce

- State minister for primary health care, Dr. Moriku Joyce, revealed to the Daily Monitor that unknown people had poisoned her. This was after toxicological investigations in Ugandan and South African laboratories confirmed the presence of arsenic poison in her body.[21]

References

- Mari F, Polettini A, Lippi D, Bertol E (December 2006). "The mysterious death of Francesco I de' Medici and Bianca Cappello: an arsenic murder?". BMJ. 333 (7582): 1299–301. doi:10.1136/bmj.38996.682234.AE. PMC 1761188. PMID 17185715. Archived from the original on 2007-01-06.

- Ericson, Lars (2004). Johan III : en biografi (in Swedish). Lund: Historiska media. p. 109. ISBN 9185057479.

- Larsson, Lars-Olof (2006). Arvet efter Gustav Vasa : en berättelse om fyra kungar och ett rike (in Swedish) (2. uppl. ed.). Stockholm: Prisma. ISBN 9151847736.

- "King George III: Mad or misunderstood?". BBC News. 2004-07-13. Archived from the original on 2009-02-13. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- "Madness of King George Linked to Arsenic - AOL News". Archived from the original on 2005-11-21.

- Straubel, Rolf (2009). Biographisches Handbuch der Preußischen Verwaltungs- und Justizbeamten 1740–1806/15. Munich: De Gruyter Saur. pp. 1040–1041. ISBN 9783598232299.

- Griffiths, Arthur. The history and romance of crime from the earliest time to the present day. 8. London: The Grolier Society. pp. 82–93.

- James G. Whorton (2011). The Arsenic Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199605996.

- "Doctors Reconsider Health and Death of 'El Libertador,' General Who Freed South America". Science Daily. April 29, 2010. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- Simon Bolivar died of arsenic poisoning Archived 2010-05-22 at the Wayback Machine 7 May 2010. Nick Allen, The Telegraph. Retrieved on 17 July 2010.

- Mowat, F. M. (1973) [1967]. The Polar Passion: The Quest for the North Pole. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. p. 124. ISBN 9780771066214.

- Parry, R. L. (2009) [2001]. Trial By Ice: The True Story of Murder and Survival on the 1871 Polaris Expedition. New York: Random House. p. 293. ISBN 9780307492128.

- Fleming, F. (2011) [2001]. Ninety Degrees North: The Quest for the North Pole. London: Granta Books. p. 142. ISBN 9781847085436.

- "Forensic scientists: China's reformist second-to-last emperor was murdered," Archived 2015-02-18 at the Wayback Machine Xinhua, November 3, 2008.

- "Arsenic killed Qing emperor, experts find," Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, October 4, 2008.

- "Phar Lap 'died from arsenic poisoning'". The Age. 19 June 2008. Archived from the original on 22 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- "Wayback Machine". Retrieved 2018-11-13.

- "Mutinta Mazoka Mmembe - Young, focused & forward thinking". Commerce gazette. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- Dooley, Brian (6 September 2017). "Munir: The Indonesian Assassination Case That Won't Go Away".

- "I'm not a crocodile: Zimbabwe's president has Lunch with the FT". Financial Times. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- "I was poisoned". 8 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

This article is issued from

Wikipedia.

The text is licensed under Creative

Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.