Angular cheilitis

Angular cheilitis (AC) is inflammation of one or both corners of the mouth.[4][5] Often the corners are red with skin breakdown and crusting.[2] It can also be itchy or painful.[2] The condition can last for days to years.[2] Angular cheilitis is a type of cheilitis (inflammation of the lips).[6]

| Angular cheilitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Rhagades,[1] perlèche,[2] cheilosis,[2] angular cheilosis,[2] commissural cheilitis,[2] angular stomatitis[2] |

| |

| Bilateral angular cheilitis in an elderly individual with false teeth, iron deficiency anemia and dry mouth | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| Symptoms | Redness, skin breakdown and crusting at the corner of the mouth[2] |

| Usual onset | Children, 30s to 60s[2] |

| Duration | Days to years[2] |

| Causes | Infection, irritation, allergies[2] |

| Treatment | Based on cause, barrier cream[2] |

| Frequency | 0.7% of the population[3] |

Angular cheilitis can be caused by infection, irritation, or allergies.[2] Infections include by fungi such as Candida albicans and bacteria such as Staph. aureus.[2] Irritants include poorly fitting dentures, licking the lips or drooling, mouth breathing resulting in a dry mouth, sun exposure, overclosure of the mouth, smoking, and minor trauma.[2] Allergies may include substances like toothpaste, makeup, and food.[2] Often a number of factors are involved.[2] Other factors may include poor nutrition or poor immune function.[2][5] Diagnosis may be helped by testing for infections and patch testing for allergies.[2]

Treatment for angular cheilitis is typically based on the underlying causes along with the use of a barrier cream.[2] Frequently an antifungal and antibacterial cream is also tried.[2] Angular cheilitis is a fairly common problem,[2] with estimates that it affects 0.7% of the population.[3] It occurs most often in the 30s to 60s, although is also relatively common in children.[2] In the developing world, iron and vitamin deficiencies are a common cause.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Angular cheilitis is a fairly non specific term which describes the presence of an inflammatory lesion in a particular anatomic site (i.e. the corner of the mouth). As there are different possible causes and contributing factors from one person to the next, the appearance of the lesion is somewhat variable. The lesions are more commonly symmetrically present on both sides of the mouth,[4] but sometimes only one side may be affected. In some cases, the lesion may be confined to the mucosa of the lips, and in other cases the lesion may extend past the vermilion border (the edge where the lining on the lips becomes the skin on the face) onto the facial skin. Initially, the corners of the mouth develop a gray-white thickening and adjacent erythema (redness).[2] Later, the usual appearance is a roughly triangular area of erythema, edema (swelling) and breakdown of skin at either corner of the mouth.[2][4] The mucosa of the lip may become fissured (cracked), crusted, ulcerated or atrophied.[2][4] There is not usually any bleeding.[7] Where the skin is involved, there may be radiating rhagades (linear fissures) from the corner of the mouth. Infrequently, the dermatitis (which may resemble eczema) can extend from the corner of the mouth to the skin of the cheek or chin.[4] If Staphylococcus aureus is involved, the lesion may show golden yellow crusts.[8] In chronic angular cheilitis, there may be suppuration (pus formation), exfoliation (scaling) and formation of granulation tissue.[2][4]

Sometimes contributing factors can be readily seen, such as loss of lower face height from poorly made or worn dentures, which results in mandibular overclosure ("collapse of jaws").[9] If there is a nutritional deficiency underlying the condition, various other signs and symptoms such as glossitis (swollen tongue) may be present. In people with angular cheilitis who wear dentures, often there may be erythematous mucosa underneath the denture (normally the upper denture), an appearance consistent with denture-related stomatitis.[4] Typically the lesions give symptoms of soreness, pain, pruritus (itching) or burning or a raw feeling.[2][9]

Causes

Angular cheilitis is thought to be multifactorial disorder of infectious origin,[10] with many local and systemic predisposing factors.[11] The sores in angular cheilitis are often infected with fungi (yeasts), bacteria, or a combination thereof;[8] this may represent a secondary, opportunistic infection by these pathogens. Some studies have linked the initial onset of angular cheilitis with nutritional deficiencies, especially of the B(B2-riboflavin) vitamins and iron (which causes iron deficiency anemia),[12] which in turn may be evidence of malnutrition or malabsorption. Angular cheilitis can be a manifestation of contact dermatitis,[13] which is considered in two groups; irritational and allergic.

Infection

The involved organisms are:

- Candida species alone (usually Candida albicans), which accounts for about 20% of cases,[14]

- Bacterial species, either:

- Staphylococcus aureus alone, which accounts for about 20% of cases,[14]

- β-hemolytic streptococci alone. These types of bacteria have been detected in between 8–15% of cases of angular cheilitis,[2] but less commonly are they present in isolation,[10]

- Or a combination of the above organisms, (a polymicrobial infection)[8] with about 60% of cases involving both C. albicans and S. aureus.[14][15]

Candida can be detected in 93% of angular cheilitis lesions.[2] This organism is found in the mouths of about 40% of healthy individuals, and it is considered by some to be normal commensal component of the oral microbiota.[2] However, Candida shows dimorphism, namely a yeast form which is thought to be relatively harmless and a pathogenic hyphal form which is associated with invasion of host tissues. Potassium hydroxide preparation is recommended by some to help distinguish between the harmless and the pathogenic forms, and thereby highlight which cases of angular cheilitis are truly caused by Candida.[2] The mouth may act as a reservoir of Candida that reinfects the sores at the corners of the mouth and prevents the sores from healing.

A lesion caused by recurrence of a latent herpes simplex infection can occur in the corner of the mouth. This is herpes labialis (a cold sore), and is sometimes termed "angular herpes simplex".[2] A cold sore at the corner of the mouth behaves similarly to elsewhere on the lips, and follows a pattern of vesicle (blister) formation followed by rupture leaving a crusted sore which resolves in about 7–10 days, and recurs in the same spot periodically, especially during periods of stress. Rather than utilizing antifungal creams, angular herpes simplex is treated in the same way as a cold sore, with topical antiviral drugs such as aciclovir.

Irritation contact dermatitis

.jpg)

22% of cases of angular cheilitis are due to irritants.[2] Saliva contains digestive enzymes, which may have a degree of digestive action on tissues if they are left in contact.[2] The corner of the mouth is normally exposed to saliva more than any other part of the lips. Reduced lower facial height (vertical dimension or facial support) is usually caused by edentulism (tooth loss), or wearing worn down, old dentures or ones which are not designed optimally. This results in overclosure of the mandible (collapse of the jaws),[9] which extenuates the angular skin folds at the corners of the mouth,[14] in effect creating an intertriginous skin crease. The tendency of saliva to pool in these areas is increased, constantly wetting the area,[10] which may cause tissue maceration and favors the development of a yeast infection.[14] As such, angular cheilitis is more commonly seen in edentulous people (people without any teeth).[9] It is by contrast uncommon in persons who retain their natural teeth.[16] Angular cheilitis is also commonly seen in denture wearers.[13] Angular cheilitis is present in about 30% of people with denture-related stomatitis.[10] It is thought that reduced vertical dimension of the lower face may be a contributing factor in up to 11% of elderly persons with angular cheilitis and in up to 18% of denture wearers who have angular cheilitis.[2] Reduced vertical dimension can also be caused by tooth migration, wearing orthodontic appliances, and elastic tissue damage caused by ultraviolet light exposure and smoking.[2]

Habits or conditions that keep the corners of the mouth moist might include chronic lip licking, thumb sucking (or sucking on other objects such as pens, pipes, lollipops), dental cleaning (e.g. flossing), chewing gum, hypersalivation, drooling and mouth breathing.[2][4][14] Some consider habitual lip licking or picking to be a form of nervous tic, and do not consider this to be true angular cheilitis,[4] instead calling it perlèche (derived from the French word pourlècher meaning "to lick one’s lips"),[2] or "factitious cheilitis" is applied to this habit.[2] The term "cheilocandidiasis" describes exfoliative (flaking) lesions of the lips and the skin around the lips, and is caused by a superficial candidal infection due to chronic lip licking.[14] Less severe cases occur during cold, dry weather, and is a form of chapped lips. Individuals may lick their lips in an attempt to provide a temporary moment of relief, only serving to worsen the condition.[17]

The sunscreen in some types of lip balm degrades over time into an irritant. Using expired lipbalm can initiate mild angular cheilitis, and when the person applies more lipbalm to alleviate the cracking, it only aggravates it. Because of the delayed onset of contact dermatitis and the recovery period lasting days to weeks, people typically do not make the connection between the causative agent and the symptoms.

Nutritional deficiencies

Several different nutritional deficiency states of vitamins or minerals have been linked to AC.[5] It is thought that in about 25% of people with AC, iron deficiency or deficiency of B vitamins are involved.[5] Nutritional deficiencies may be a more common cause of AC in Third World countries.[5] Chronic iron deficiency may also cause koilonychia (spoon shaped deformity of the fingernails) and glossitis (inflammation of the tongue). It is not completely understood how iron deficiency causes AC, but it is known that it causes a degree of immunocompromise (decreased efficiency of the immune system) which may in turn allow an opportunistic infection of candida.[5] Vitamin B2 deficiency (ariboflavinosis) may also cause AC, and other conditions such as redness of mucous membranes, magenta colored glossitis (pink inflammation of the tongue).[5] Vitamin B5 deficiency may also cause AC, along with glossitis, and skin changes similar to seborrhoeic dermatitis around the eyes, nose and mouth.[5] Vitamin B12 deficiency is sometimes responsible for AC, and commonly occurs together with folate deficiency (a lack of folic acid), which also causes glossitis and megaloblastic anemia.[5] Vitamin B3 deficiency (pellagra) is another possible cause, and in which other association conditions such as dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia and glossitis can occur.[5] Biotin (vitamin B7) deficiency has also been reported to cause AC, along with hair loss (alopecia) and dry eyes.[5] Zinc deficiency is known to cause AC.[18] Other symptoms may include diarrhea, alopecia and dermatitis.[5] Acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder causing impaired absorption of zinc, and is associated with AC.[5]

In general, these nutritional disorders may be caused by malnutrition, such as may occur in alcoholism or in poorly considered diets, or by malabsorption secondary to gastrointestinal disorders (e.g. Coeliac disease or chronic pancreatitis) or gastrointestinal surgeries (e.g. pernicious anemia caused by ileal resection in Crohn's disease).[5]

Systemic disorders

Some systemic disorders are involved in angular cheilitis by virtue of their association with malabsorption and the creation of nutritional deficiencies described above. Such examples include people with anorexia nervosa.[5] Other disorders may cause lip enlargement (e.g. orofacial granulomatosis),[5] which alters the local anatomy and extenuates the skin folds at the corners of the mouth. More still may be involved because they affect the immune system, allowing normally harmless organisms like Candida to become pathogenic and cause an infection. Xerostomia (dry mouth) is thought to account for about 5% of cases of AC.[5] Xerostomia itself has many possible causes, but commonly the cause may be side effects of medications, or conditions such as Sjögren's syndrome. Conversely, conditions which cause drooling or sialorrhoea (excessive salivation) can cause angular cheilitis by creating a constant wet environment in the corners of the mouth. About 25% of people with Down syndrome appear to have AC.[5] This is due to relative macroglossia, an apparently large tongue in a small mouth, which may constantly stick out of the mouth causing maceration of the corners of the mouth with saliva. Inflammatory bowel diseases (such as Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis) can be associated with angular cheilitis.[4] In Crohn's, it is likely the result of malabsorption and immunosuppressive therapy which gives rise to the sores at the corner of the mouth.[9] Glucagonomas are rare pancreatic endocrine tumors which secrete glucagon, and cause a syndrome of dermatitis, glucose intolerance, weight loss and anemia. AC is a common feature of glucagonoma syndrome.[19] Infrequently, angular cheilitis may be one of the manifestations of chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis,[14] and sometimes cases of oropharyngeal or esophageal candidiasis may accompany angular cheilitis.[2] Angular cheilitis may be present in human immunodeficiency virus infection,[11] neutropenia,[16] or diabetes.[4] Angular cheilitis is more common in people with eczema because their skin is more sensitive to irritants.[2] Other conditions possibly associated include plasma cell gingivitis,[7] Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome,[5] or sideropenic dysphagia (also called Plummer-Vinson syndrome or Paterson-Brown-Kelly syndrome).[5]

Drugs

Several drugs may cause AC as a side effect, by various mechanisms, such as creating drug-induced xerostomia. Various examples include isotretinoin, indinavir, and sorafenib.[5] Isotretinoin (Accutane), an analog of vitamin A, is a medication which dries the skin. Less commonly, angular cheilitis is associated with primary hypervitaminosis A,[20] which can occur when large amounts of liver (including cod liver oil and other fish oils) are regularly consumed or as a result from an excess intake of vitamin A in the form of vitamin supplements. Recreational drug users may develop AC. Examples include cocaine, methamphetamines, heroin, and hallucinogens.[5]

Allergic contact dermatitis

Allergic reactions may account for about 25–34% of cases of generalized cheilitis (i.e., inflammation not confined to the angles of the mouth). It is unknown how frequently allergic reactions are responsible for cases of angular cheilitis, but any substance capable of causing generalized allergic cheilitis may present involving the corners of the mouth alone.

Examples of potential allergens include substances that may be present in some types of lipstick, toothpaste, acne products, cosmetics, chewing gum, mouthwash, foods, dental appliances, and materials from dentures or mercury containing amalgam fillings.[2] It is usually impossible to tell the difference between irritant contact dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis without a patch test.

Loss of lower facial height

Severe tooth wear or ill fitting dentures may cause wrinkling at the corners of the lip that creates a favorable environment for the condition.[21] This can be corrected with onlays or crowns on the worn teeth to restore height or new dentures with "taller" teeth. The loss of vertical dimension has been associated with angular cheilitis in older individuals with an increase in facial laxity.[22]

Diagnosis

Angular cheilitis is normally a diagnosis made clinically. If the sore is unilateral, rather than bilateral, this suggests a local factor (e.g., trauma) or a split syphilitic papule.[4][23] Angular cheilitis caused by mandibular overclosure, drooling, and other irritants is usually bilateral.[2]

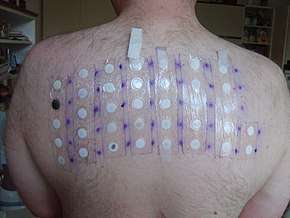

The lesions are normally swabbed to detect if Candida or pathogenic bacterial species may be present. Persons with angular cheilitis who wear dentures often also will have their denture swabbed in addition. A complete blood count (full blood count) may be indicated, including assessment of the levels of iron, ferritin, vitamin B12 (and possibly other B vitamins), and folate.[4]

Classification

Angular cheilitis could be considered to be a type of cheilitis or stomatitis. Where Candida species are involved, angular cheilitis is classed as a type of oral candidiasis, specifically a primary (group I) Candida-associated lesion.[11] This form angular cheilitis which is caused by Candida is sometimes termed "Candida-associated angular cheilitis",[11] or less commonly, "monilial perlèche".[2] Angular cheilitis can also be classified as acute (sudden, short-lived appearance of the condition) or chronic (lasts a long time or keeps returning), or refractory (the condition persists despite attempts to treat it).[2]

Management

There are 4 aspects to the treatment of angular cheilitis.[24] Firstly, potential reservoirs of infection inside the mouth are identified and treated.[24] Oral candidiasis, especially denture-related stomatitis is often found to be present where there is angular cheilitis, and if it is not treated, the sores at the corners of the mouth may often recur.[8][13] This involves having dentures properly fitted and disinfected. Commercial preparations are marketed for this purpose, although dentures may be left in dilute (1:10 concentration) household bleach overnight, but only if they are entirely plastic and do not contain any metal parts, and with rinsing under clean water before use.[9] Improved denture hygiene is often required thereafter, including not wearing the denture during sleep and cleaning it daily.[4] For more information, see Denture-related stomatitis.

Secondly, there may be a need to increase the vertical dimension of the lower face to prevent overclosure of the mouth and formation of deep skin folds.[24] This may require the construction of a new denture with an adjusted bite.[4] Rarely, in cases resistant to normal treatments, surgical procedures such as collagen injections (or other facial fillers such as autologous fat or crosslinked hyaluronic acid) are used in an attempt to restore the normal facial contour.[2][4] Other measures which seek to reverse the local factors that may be contributing to the condition include improving oral hygiene, stopping smoking or other tobacco habits and use of a barrier cream (e.g. zinc oxide paste) at night.[2]

Thirdly, treatment of the infection and inflammation of the lesions themselves is addressed. This is usually with topical antifungal medication,[8] such as clotrimazole,[14] amphotericin B,[24] ketoconazole,[16] or nystatin cream.[9] Some antifungal creams are combined with corticosteroids such as hydrocortisone[8] or triamcinolone[9] to reduce inflammation, and certain antifungals such as miconazole also have some antibacterial action.[8] Diiodohydroxyquinoline is another topical therapy for angular cheilitis.[14] If Staphylococcus aureus infection is demonstrated by microbiological culture to be responsible (or suspected), the treatment may be changed to fusidic acid cream,[8] an antibiotic which is effective against this type of bacteria. Aside from fusidic acid, neomycin,[24] mupirocin,[2] metronidazole,[7] and chlorhexidine[24] are alternative options in this scenario.

Finally, if the condition appears resistant to treatment, investigations for underlying causes such as anemia or nutrient deficiencies or HIV infection.[24] Identification of the underlying cause is essential for treating chronic cases. The lesions may resolve when the underlying disease is treated, e.g. with a course of oral iron or B vitamin supplements.[4] Patch testing is recommended by some in cases which are resistant to treatment and where allergic contact dermatitis is suspected.[2]

Prognosis

Most cases of angular cheilitis respond quickly when antifungal treatment is used.[16] In more long standing cases, the severity of the condition often follows a relapsing and remitting course over time.[14] The condition can be difficult to treat and can be prolonged.[4]

Epidemiology

AC is a relatively common condition,[11] accounting for between 0.7 – 3.8% of oral mucosal lesions in adults and between 0.2 – 15.1% in children, though overall it occurs most commonly in adults in the third to sixth decades of life.[2][4] It occurs worldwide, and both males and females are affected.[4] Angular cheilitis is the most common presentation of fungal and bacterial infections of the lips.[14]

Etymology

The term "angular cheilitis" is from Ancient greek, χείλος meaning lip and -itis meaning inflammation.

References

- Pindborg, Jens Jørgen (1973). Atlas of Diseases of the Oral Mucosa. Saunders. ISBN 9780721672649. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

Angular cheilosis: The lateral lip fissures, well known among denture wearers, have been called by a variety of names, such as "rhagades", "perleche", "angular cheilitis", and "angular cheilosis".

- Park, KK; Brodell, RT; Helms, SE (June 2011). "Angular cheilitis, part 1: local etiologies". Cutis. 87 (6): 289–95. PMID 21838086.

- Lyons, Faye (2014). Dermatology for the Advanced Practice Nurse. Springer Publishing Company. p. 95. ISBN 9780826136442. Archived from the original on 2016-08-16.

- Scully, Crispian (2008). Oral and maxillofacial medicine : the basis of diagnosis and treatment (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 147–49. ISBN 9780443068188.

- Park, KK; Brodell RT; Helms SE. (July 2011). "Angular cheilitis, part 2: nutritional, systemic, and drug-related causes and treatment" (PDF). Cutis. 88 (1): 27–32. PMID 21877503. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-19.

- Martin, Elizabeth (2015). Concise Medical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 136. ISBN 9780199687817. Archived from the original on 2016-08-16.

- Wood, NK; Goaz, PW (1997). Differential diagnosis of oral and maxillofacial lesions (5th ed.). St. Louis [u.a.]: Mosby. pp. 64–65, 85. ISBN 978-0815194323.

- Coulthard P, Horner K, Sloan P, Theaker E (2008). Master dentistry volume 1, oral and maxillofacial surgery, radiology, pathology and oral medicine (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 180–81. ISBN 9780443068966.

- Treister NS, Bruch JM (2010). Clinical oral medicine and pathology. New York: Humana Press. pp. 92–93, 144. ISBN 978-1-60327-519-4.

- Soames JV, Southam JC, JV (1999). Oral pathology (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 197–98. ISBN 978-0192628947.

- Tyldesley WR, Field A, Longman L (2003). Tyldesley's Oral medicine (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 37, 40, 46, 63–67. ISBN 978-0192631473.

- MedlinePlus (2005-08-01). "Riboflavin (vitamin B2) deficiency (ariboflavinosis)". National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2010-07-24.

- Peter C. Schalock, M.D.; Jeffrey T. S. Hsu, M.D.; Kenneth A. Arndt, eds. (2010-09-15). Primary Care Dermatology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-7817-9378-0. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CA, Bouquot JE (2002). Oral & maxillofacial pathology (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 100, 192, 196, 266. ISBN 978-0721690032.

- Kerawala C; Newlands C, eds. (2010). Oral and maxillofacial surgery. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 446. ISBN 9780199204830.

- Greenberg MS, Glick M (2003). Burket's oral medicine diagnosis & treatment (10th ed.). Hamilton, Ont.: BC Decker. pp. 97–98, 550. ISBN 978-1550091861.

- Gibson, Lawrence E., M.D., "Dry Skin" Archived 2009-09-15 at the Wayback Machine, Mayo Clinic

- Gaveau D, Piette F, Cortot A, Dumur V, Bergoend H (1987). "[Cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency in ethylic cirrhosis]". Ann Dermatol Venereol. 114 (1): 39–53. PMID 3579131.

- Tadataka Yamada; David Alpers; Anthony Kalloo; Neil Kaplowitz; Chung Owyang; Don Powell, eds. (2009). Textbook of gastroenterology (5th ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Blackwell Pub. pp. 1882–83. ISBN 978-1-4051-6911-0.

- Kliegman: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18th ed.

- Devani, Alim; Barankin, Benjamin (2007). "Answer: Can you identify this condition?". Canadian Family Physician. 53 (6): 1022–1023. ISSN 0008-350X. PMC 1949217.

- "How Do I Manage a Patient with Angular Cheilitis? | jcda". www.jcda.ca. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Leyse-Wallace, Ruth (29 January 2013). Nutrition and Mental Health. CRC Press. p. 246. ISBN 9781439863350. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- Samaranayake, LP (2009). Essential microbiology for dentistry (3rd ed.). Elseveier. pp. 296–97. ISBN 978-0702041679.