Akinete

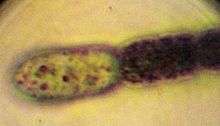

An akinete is an enveloped, thick-walled, non-motile, dormant cell formed by filamentous, heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria under the order Nostocales and Stigonematales.[1][2][3][4] Akinetes are resistant to cold and desiccation.[1] They also accumulate and store various essential material, both of which allows the akinete to serve as a survival structure for up to many years.[1][4] However, akinetes are not resistant to heat.[1] Akinetes usually develop in strings with each cell differentiating after another and this occurs next to heterocysts if they are present.[1] Development usually occurs during stationary phase and is triggered by unfavorable conditions such as insufficient light or nutrients, temperature, and saline levels in the environment.[1][4] Once conditions become more favorable for growth, the akinete can then germinate back into a vegetative cell.[5] Increased light intensity, nutrients availability, oxygen availability, and changes in salinity are important triggers for germination.[5] In comparison to vegetative cells, akinetes are generally larger.[4][6] This is associated with the accumulation of nucleic acids which is important for both dormancy and germination of the akinete.[6] Despite being a resting cell, it is still capable of some metabolic activities such as photosynthesis, protein synthesis, and carbon fixation, albeit at significantly lower levels.[3]

Akinetes can remain dormant for extended periods of time. Studies have shown that some species could be cultured that were 18 and 64 years old. [7]

Akinete formation also influences the perennial blooms of cyanobacteria.[8]

References

- Adams, David; Duggan, Paula (Aug 1999). "Heterocyst and akinete differentiation in cyanobacteria". New Phytol. 144: 23–28. doi:10.1046/j.1469-8137.1999.00505.x.

- Moore, R. et al. (1998) Botany. 2nd Ed. WCB/McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-697-28623-1

- Sukenik, Assaf; Beardall, John; Hadas, Ora (July 2007). "PHOTOSYNTHETIC CHARACTERIZATION OF DEVELOPING AND MATURE AKINETES OF APHANIZOMENON OVALISPORUM (CYANOPROKARYOTA)". Journal of Phycology. 43: 780–788. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2007.00374.x.

- Sukenik, Assaf; Maldener, Iris; Delhaye, Thomas (September 2015). "Carbon assimilation and accumulation of cyanophycin during the development of dormant cells (akinetes) in the cyanobacterium Aphanizomenon ovalisporum". Front. Microbiol.

- Myers, Jackie; Beardall, John; Allinson, Graeme (July 2010). "Environmental influences on akinete germination and development in Nodularia spumigena (Cyanobacteriaceae), isolated from the Gippsland Lakes, Victoria, Australia". Hydrobiologia. 649 (1): 239–247. doi:10.1007/s10750-010-0252-5.

- Sukenik, Assaf; Kaplan-Levy, Ruth; Mark, Jessica (March 2012). "Massive multiplication of genome and ribosomes in dormant cells (akinetes) of Aphanizomenon ovalisporum (Cyanobacteria)". The ISME Journal. 6 (3): 670–679. doi:10.1038/ismej.2011.128. PMC 3280138.

- David Livingstone & G.H.M. Jaworski (1980) The viability of akinetes of blue-green algae recovered from the sediments of Rostherne Mere, British Phycological Journal, 15:4, 357-364, DOI: 10.1080/00071618000650361

- Myers, Jackie; Beardall, John (Aug 2011). "Potential triggers of akinete differentiation in Nodularia spumigena (Cyanobacteriaceae) isolated from Australia". Hydrobiologia. 671 (1): 165. doi:10.1007/s10750-011-0714-4.