Gastritis

Gastritis is inflammation of the lining of the stomach.[1] It may occur as a short episode or may be of a long duration.[1] There may be no symptoms but, when symptoms are present, the most common is upper abdominal pain.[1] Other possible symptoms include nausea and vomiting, bloating, loss of appetite and heartburn.[1][2] Complications may include stomach bleeding, stomach ulcers, and stomach tumors.[1] When due to autoimmune problems, low red blood cells due to not enough vitamin B12 may occur, a condition known as pernicious anemia.[3]

| Gastritis | |

|---|---|

| |

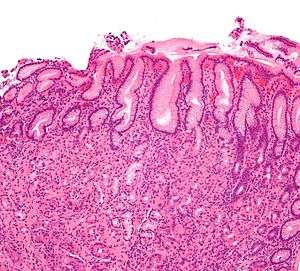

| Micrograph showing gastritis. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Upper abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, bloating, loss of appetite, heartburn[1][2] |

| Complications | Bleeding, stomach ulcers, stomach tumors, pernicious anemia[1][3] |

| Duration | Short or long term[1] |

| Causes | Helicobacter pylori, NSAIDs, alcohol, smoking, cocaine, severe illness, autoimmune problems[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Endoscopy, upper gastrointestinal series, blood tests, stool tests[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Myocardial infarction, inflammation of the pancreas, gallbladder problems, peptic ulcer disease[2] |

| Treatment | Antacids, H2 blockers, proton pump inhibitors, antibiotics[1] |

| Frequency | ~50% of people[4] |

| Deaths | 50,000 (2015)[5] |

Common causes include infection with Helicobacter pylori and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).[1] Less common causes include alcohol, smoking, cocaine, severe illness, autoimmune problems, radiation therapy and Crohn's disease.[1][6] Endoscopy, a type of X-ray known as an upper gastrointestinal series, blood tests, and stool tests may help with diagnosis.[1] The symptoms of gastritis may be a presentation of a myocardial infarction.[2] Other conditions with similar symptoms include inflammation of the pancreas, gallbladder problems, and peptic ulcer disease.[2]

Prevention is by avoiding things that cause the disease.[4] Treatment includes medications such as antacids, H2 blockers, or proton pump inhibitors.[1] During an acute attack drinking viscous lidocaine may help.[7] If gastritis is due to NSAIDs these may be stopped.[1] If H. pylori is present it may be treated with a combination of antibiotics such as amoxicillin and clarithromycin.[1] For those with pernicious anemia, vitamin B12 supplements are recommended either by mouth or by injection.[3] People are usually advised to avoid foods that bother them.[8]

Gastritis is believed to affect about half of people worldwide.[4] In 2013 there were approximately 90 million new cases of the condition.[9] As people get older the disease becomes more common.[4] It, along with a similar condition in the first part of the intestines known as duodenitis, resulted in 50,000 deaths in 2015.[5] H. pylori was first discovered in 1981 by Barry Marshall and Robin Warren.[10]

Signs and symptoms

Many people with gastritis experience no symptoms at all. However, upper central abdominal pain is the most common symptom; the pain may be dull, vague, burning, aching, gnawing, sore, or sharp.[11] Pain is usually located in the upper central portion of the abdomen,[12] but it may occur anywhere from the upper left portion of the abdomen around to the back.

Other signs and symptoms may include the following:

- Nausea

- Vomiting (may be clear, green or yellow, blood-streaked or completely bloody depending on the severity of the stomach inflammation)

- Belching (does not usually relieve stomach pain if present)

- Bloating

- Early satiety[11]

- Loss of appetite

- Unexplained weight loss

Cause

Common causes include Helicobacter pylori and NSAIDs.[1] Less common causes include alcohol, cocaine, severe illness and Crohn disease, among others.[1] Cases of exercise induced bleeding as a result of gastritis have also been reported.[13] Other causes may include Helicobacter heilmannii sensu lato.[14]

Helicobacter pylori

Helicobacter pylori colonizes the stomachs of more than half of the world's population, and the infection continues to play a key role in the pathogenesis of a number of gastroduodenal diseases. Colonization of the gastric mucosa with Helicobacter pylori results in the development of chronic gastritis in infected individuals, and in a subset of patients chronic gastritis progresses to complications (e.g., ulcer disease, stomach cancers, some distinct extragastric disorders).[15] However, over 80 percent of individuals infected with the bacterium are asymptomatic and it has been postulated that it may play an important role in the natural stomach ecology.[16]

Critical illness

Gastritis may also develop after major surgery or traumatic injury ("Cushing ulcer"), burns ("Curling ulcer"), or severe infections. Gastritis may also occur in those who have had weight loss surgery resulting in the banding or reconstruction of the digestive tract.

Diet

Evidence does not support a role for specific foods including spicy foods and coffee in the development of peptic ulcers.[17] People are usually advised to avoid foods that bother them.[8]

Pathophysiology

Active gastritis is characterized by granulocyte and agranulocyte infiltration of the mucosa of the antrum and body.[18][19]. The term pangastritis refers to an inflammation in the stomach as a whole.

Acute

Acute gastritis refers to how fast the symptoms have come on.[20] NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase-1, or COX-1, an enzyme responsible for the biosynthesis of eicosanoids in the stomach, which increases the possibility of peptic ulcers forming.[21] Also, NSAIDs, such as aspirin, reduce a substance that protects the stomach called prostaglandin. These drugs used in a short period are not typically dangerous. However, regular use can lead to gastritis.[22] Additionally, severe physiologic stress ("stress ulcers") from sepsis, hypoxia, trauma, or surgery, is also a common etiology for acute erosive gastritis. This form of gastritis can occur in more than 5% of hospitalized patients.

Also, note that alcohol consumption does not cause chronic gastritis. It does, however, erode the mucosal lining of the stomach; low doses of alcohol stimulate hydrochloric acid secretion. High doses of alcohol do not stimulate secretion of acid.[23] It differs from active gastritis which is when neutrophils are present.[20]

Chronic

Chronic gastritis refers to a wide range of problems of the gastric tissues.[19] The immune system makes proteins and antibodies that fight infections in the body to maintain a homeostatic condition. In that case, the immune system attacks the stomach. In some cases bile, normally used to aid digestion in the small intestine, will enter through the pyloric valve of the stomach if it has been removed during surgery or does not work properly, also leading to gastritis. Gastritis may also be caused by other medical conditions, including HIV/AIDS, Crohn's disease, certain connective tissue disorders, and liver or kidney failure. Since 1992, chronic gastritis lesions are classified according to the Sydney system, a system in which the primary goal is to provide guidelines related to the aspect of biopsies and how to write a report.[24]

Metaplasia

Mucous gland metaplasia, the reversible replacement of differentiated cells, occurs in the setting of severe damage of the gastric glands, which then waste away (atrophic gastritis) and are progressively replaced by mucous glands. Gastric ulcers may develop; it is unclear if they are the causes or the consequences. Intestinal metaplasia typically begins in response to chronic mucosal injury in the antrum, and may extend to the body. Gastric mucosa cells change to resemble intestinal mucosa and may even assume absorptive characteristics. Intestinal metaplasia is classified histologically as complete or incomplete. With complete metaplasia, gastric mucosa is completely transformed into small-bowel mucosa, both histologically and functionally, with the ability to absorb nutrients and secrete peptides. In incomplete metaplasia, the epithelium assumes a histologic appearance closer to that of the large intestine and frequently exhibits dysplasia.[19]

Collagenous gastritis

Collagenous gastritis (CG) is a rare form of chronic gastritis characterised by the deposition of subepithelial collagen band thicker than 10 μm and a chronic inflammation of the lamina propria. The clinical features for the children and adults are generally not the same. Children often present symtpoms of iron anemia and the adults with gastrointestinal tract involvement, being associated with collagenous colitis or collagenous sprue, and chronic watery diarrhea. There is no established treatment for CG.[25]

Diagnosis

Often, a diagnosis can be made based on the person's description of their symptoms, but other methods which may be used to verify gastritis include:

- Blood tests:

- Blood cell count

- Presence of H. pylori

- Liver, kidney, gallbladder, or pancreas functions

- Biomarkers count such as pepsinogen 3, group I (pepsinogen A) (PGI), progastricsin (PGII) and little gastrin I (G-17). PGII alone is considered as a reliable biomarker of gastric inflamation[26]

- Stool sample, to look for blood or signs of H. pylori infection in the stool[1]

- Upper GI series to check for signs of gastritis or gastropathy[1]

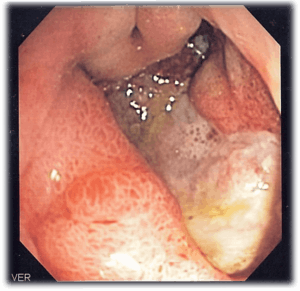

- Endoscopy, to check for stomach lining inflammation and mucous erosion

- Stomach biopsy, to test for gastritis and other conditions[27]

Treatment

Antacids are a common treatment for mild to medium gastritis.[28] When antacids do not provide enough relief, medications such as H2 blockers and proton-pump inhibitors that help reduce the amount of acid are often prescribed.[28][29]

Cytoprotective agents are designed to help protect the tissues that line the stomach and small intestine.[30] They include the medications sucralfate, rebamipide,[31] and misoprostol. If NSAIDs are being taken regularly, one of these medications to protect the stomach may also be taken. Another cytoprotective agent is bismuth subsalicylate.

Several regimens are used to treat H. pylori infection. Most use a combination of two antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor. Sometimes bismuth is added to the regimen.

History

In 1,000 A.D, Avicenna first gave the description of stomach cancer. In 1728, German physician Georg Ernst Stahl first coined the term "gastritis". Italian anatomical pathologist Giovanni Battista Morgagni further described the characteristics of gastric inflammation. He described the characteristics of erosive or ulcerative gastritis and erosive gastritis. Between 1808 and 1831, French physician François-Joseph-Victor Broussais gathered information from the autopsy of the dead French soldiers. He described chronic gastritis as "Gastritide" and erroneously believed that gastritis was the cause of ascites, typhoid fever, and meningitis. In 1854, Charles Handfield Jones and Wilson Fox described the microscopic changes of stomach inner lining in gastritis which existed in diffuse and segmental forms. In 1855, Baron Carl von Rokitansky first described hypetrophic gastritis. In 1859, British physician, William Brinton first described about acute, subacute, and chronic gastritis. In 1870, Samuel Fenwick noted that pernicious anemia causes glandular atrophy in gastritis. German surgeon, Georg Ernst Konjetzny noticed that gastric ulcer and gastric cancer are the result of gastric inflammation. Shields Warren and Willam A. Meissner described the intestinal metaplasia of the stomach as a feature of chronic gastritis.

See also

References

- "Gastritis". The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). November 27, 2013. Archived from the original on 6 March 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- Rosen & Barkin's 5-Minute Emergency Medicine Consult (4 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2012. p. 447. ISBN 9781451160970. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02.

- Varbanova, M.; Frauenschläger, K.; Malfertheiner, P. (Dec 2014). "Chronic gastritis - an update". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Gastroenterology. 28 (6): 1031–42. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2014.10.005. PMID 25439069.

- Fred F. Ferri (2012). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2013,5 Books in 1, Expert Consult - Online and Print,1: Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2013. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 417. ISBN 9780323083737. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- GBD 2015 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- Hauser, Stephen (2014). Mayo Clinic Gastroenterology and Hepatology Board Review. Oxford University Press. p. 49. ISBN 9780199373338. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- Adams (2012). "32". Emergency Medicine: Clinical Essentials. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781455733941. Archived from the original on 2016-08-15.

- Webster-Gandy, Joan; Madden, Angela; Holdsworth, Michelle, eds. (2012). Oxford handbook of nutrition and dietetics (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press, USA. p. 571. ISBN 9780199585823. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators (22 August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMC 4561509. PMID 26063472.

- Wang, AY; Peura, DA (October 2011). "The prevalence and incidence of Helicobacter pylori-associated peptic ulcer disease and upper gastrointestinal bleeding throughout the world". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America. 21 (4): 613–35. doi:10.1016/j.giec.2011.07.011. PMID 21944414.

- "Gastritis Symptoms". eMedicineHealth. 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-12-06. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- "Gastritis". National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. December 2004. Archived from the original on 2008-10-11. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- Moses FM (March 1990). "The Effect of Exercise on the Gastrointestinal Tract". Sports Medicine. 9 (3): 159–172. doi:10.2165/00007256-199009030-00004. PMID 2180030.

- Zhang, Lizhi; Chandan, Vishal S.; Wu, Tsung-Teh (2019). Surgical Pathology of Non-neoplastic Gastrointestinal Diseases. Springer. p. 129. ISBN 978-3-030-15573-5.

- Kandulski A, Selgrad M, Malfertheiner P (August 2008). "Helicobacter pylori infection: a clinical overview". Digestive and Liver Disease. 40 (8): 619–26. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2008.02.026. PMID 18396114.

- Blaser, M. J. (2006). "Who are we? Indigenous microbes and the ecology of human diseases" (PDF). EMBO Reports. 7 (10): 956–60. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400812. PMC 1618379. PMID 17016449. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-11-05.

- Raphael Rubin; David S. Strayer; Emanuel Rubin, eds. (2012). Rubin's pathology : clinicopathologic foundations of medicine (Sixth ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 623. ISBN 9781605479682. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02.

- Sipponen, Pentti and Price, Ashley B (January 2011). "The Sydney System for classification of gastritis 20 years ago". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 26: 31–4. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06536.x. PMID 21199511.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Gastritis". Merck. January 2007. Archived from the original on 2009-01-25. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- Zhang, Lizhi; Chandan, Vishal S.; Wu, Tsung-Teh (2019). Surgical Pathology of Non-neoplastic Gastrointestinal Diseases. Springer. p. 122. ISBN 978-3-030-15573-5.

- Dajani EZ, Islam K (August 2008). "Cardiovascular and gastrointestinal toxicity of selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors in man" (PDF). Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 59 (Suppl 2): 117–33. PMID 18812633.

- Siegelbaum, Jackson (2006). "Gastritis". Jackson Siegelbaum Gastroenterology. Archived from the original on 2008-12-16. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- Wolff G (1989). "[Effect of alcohol on the stomach]" [Effect of alcohol on the stomach]. Gastroenterologisches Journal (in German). 49 (2): 45–9. PMID 2679657.

- Mayo Clinic Staff (April 13, 2007). "Gastritis". MayoClinic. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- Zhang, Lizhi; Chandan, Vishal S.; Wu, Tsung-Teh (2019). Surgical Pathology of Non-neoplastic Gastrointestinal Diseases. Springer. p. 139. ISBN 978-3-030-15573-5.

- Barchi Alberto, Miraglia Chiara, Violi Alessandra, Cambiè Ginevra, Nouvenne Antonio, Capasso Mario, Leandro Gioacchino, Meschi Tiziana, Luigi de’ Angelis Gian, and Di Mario Francesco (2018). "A non-invasive method for the diagnosis of upper GI diseases". Acta Biomedica. 89 (8–S): 44–52. doi:10.23750/abm.v89i8-S.7917. PMC 6502204. PMID 30561417.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Exams and Tests". eMedicinHealth. 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-12-11. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- Zajac, P; Holbrook, A; Super, ME; Vogt, M (March–April 2013). "An overview: Current clinical guidelines for the evaluation, diagnosis, treatment, and management of dyspepsia". Osteopathic Family Physician. 5 (2): 79–85. doi:10.1016/j.osfp.2012.10.005.

- Boparai V, Rajagopalan J, Triadafilopoulos G (2008). "Guide to the use of proton pump inhibitors in adult patients". Drugs. 68 (7): 925–47. doi:10.2165/00003495-200868070-00004. PMID 18457460.

- Fashner, J; Gitu, AC (15 February 2015). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Peptic Ulcer Disease and H. pylori Infection". American Family Physician. 91 (4): 236–42. PMID 25955624.

- Jaafar, MH; Safi, SZ; Tan, MP; Rampal, S; Mahadeva, S (May 2018). "Efficacy of Rebamipide in Organic and Functional Dyspepsia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 63 (5): 1250–1260. doi:10.1007/s10620-017-4871-9. PMID 29192375.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |