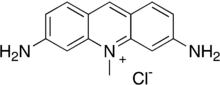

Acriflavine

Acriflavine (INN: acriflavinium chloride) is a topical antiseptic. It has the form of an orange or brown powder. It may be harmful in the eyes or if inhaled. It is a dye and it stains the skin and may irritate. The hydrochloride form is more irritating than the neutral form. It is derived from acridine. Commercial preparations are often mixtures with proflavine.[1] It is known by a variety of commercial names.

| |

Sample of pure acriflavine | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

3,6-Diamino-10-methylacridin-10-ium chloride | |

| Other names

Acriflavinium chloride (INN) | |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.211.047 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula |

C14H14ClN3 |

| Molar mass | 259.74 g·mol−1 |

| Pharmacology | |

| R02AA13 (WHO) QG01AC90 (WHO) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Uses

Medical use

Acriflavine was developed in 1912 by Paul Ehrlich, a German medical researcher, and was used during the First World War against sleeping sickness and as a topical antiseptic.[2]

Other uses

Acriflavine is used in biochemistry for fluorescently labeling high molecular weight RNA.[1]

It is used as treatment for external fungal infections of aquarium fish.[3]

Research

In an animal model, acriflavine has been shown to inhibit HIF-1, which prevents blood vessels growing to supply tumors with blood and interferes with glucose uptake and use.[4]

Acriflavine might be effective in fighting common cold virus, and also aid the fight against increasingly antibiotic resistant bacteria [5][6][7] because it can cure (remove) plasmids containing antimicrobial resistance genes from Gram positive bacteria [8].

Since 2014, acriflavine has been undergoing testing as an antimalarial drug to treat parasites with resistance to quinine and modern anti-parasitic medicines. [9]

Legal status

Australia

Acriflavine is a controlled substance in Australia and dependent on situation, is considered either a Schedule 5 (Caution) or Schedule 7 (Dangerous Poison) substance. The use, storage and preparation of the chemical is subject to strict state and territory laws.

References

- "Acriflavine". Sigma-Aldrich.

- acriflavine Encyclopædia Britannica

- Acriflavine use in aquaria

- Lee, K.; Zhang, H.; Qian, D. Z.; Rey, S.; Liu, J. O.; Semenza, G. L. (2009). "Acriflavine inhibits HIF-1 dimerization, tumor growth, and vascularization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (42): 17910. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10617910L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909353106. PMC 2764905. PMID 19805192.

- "Antiseptic used in WWI could hold key to treating superbugs, viral infections, Melbourne researchers say". ABC. November 28, 2016.

- "This forgotten WWI antiseptic could be the key to fighting antibiotic resistance". Science Alert. November 30, 2016.

- Pépin, Geneviève; Nejad, Charlotte; Thomas, Belinda J; Ferrand, Jonathan; McArthur, Kate; Bardin, Philip G; Williams, Bryan R.G; Gantier, Michael P (2016). "Activation of cGAS-dependent antiviral responses by DNA intercalating agents". Nucleic Acids Research. 45 (1): 198–205. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw878. PMC 5224509. PMID 27694309.

- Mesas, J.M.; Rodriguez, M.C.; Alegre, M.T. (2004). "Plasmid curing of Oenococcus oeni". Plasmid. 51 (1): 37–40. doi:10.1016/S0147-619X(03)00074-X.

- Dana, Srikanta; Prusty, Dhaneswar; Dhayal, Devender; Gupta, Mohit Kumar; Dar, Ashraf; Sen, Sobhan; Mukhopadhyay, Pritam; Adak, Tridibesh; Dhar, Suman Kumar (2014). "Potent Antimalarial Activity of Acriflavine In Vitroand In Vivo". ACS Chemical Biology. 9 (10): 2366. doi:10.1021/cb500476q. PMC 4201339. PMID 25089658.

External links

- ChemExper Chemical Directory