Vaginal bleeding

Vaginal bleeding is any bleeding through the vagina, including bleeding from the vaginal wall itself, as well as (and more commonly) bleeding from another location of the female reproductive system, often the uterus.[1] Generally, it is either part of a normal menstrual cycle or is caused by hormonal or other problems of the reproductive system, such as abnormal uterine bleeding.

| Vaginal bleeding | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Gynecology |

Vaginal bleeding during pregnancy may indicate a possible pregnancy complication that needs to be medically addressed. Blood loss per vaginam (Latin: through the vagina) (PV) typically arises from the lining of the uterus (endometrium), but may arise from uterine or cervical lesions, the vagina, and rarely from the fallopian tube. During pregnancy it is usually but not always related to the pregnancy itself.

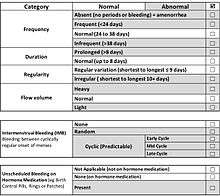

Regular monthly vaginal bleeding during the reproductive years, menstruation, is a normal physiologic process. During the reproductive years, bleeding that is excessively heavy (menorrhagia or heavy menstrual bleeding), occurs between monthly menstrual periods (intermenstrual bleeding), occurs more frequently than every 21 days (abnormal uterine bleeding), occurs too infrequently (oligomenorrhea), or occurs after vaginal intercourse (postcoital bleeding) should be evaluated.

The causes of abnormal vaginal bleeding vary by age,[2] and such bleeding can be a sign of specific medical conditions ranging from hormone imbalances or anovulation to malignancy (cervical cancer, vaginal cancer or uterine cancer). In young children, or elderly adults with cognitive impairment, the source of bleeding may not be obvious, and may be from the urinary tract (hematuria) or the rectum rather than the vagina, although most adult women can identify the site of bleeding.[3] When vaginal bleeding occurs in prepubertal children or in postmenopausal women, it always needs investigation.[4][5][3]

Differential diagnosis

The parameters for normal menstruation have been defined as a result of an international process designed to simplify terminologies and definitions for abnormalities of menstrual bleeding.[6][7] The causes of abnormal vaginal bleeding vary by age.[2]

Bleeding in children

Bleeding in children is of concern if it occurs before the expected time of menarche and in the absence of appropriate pubertal development. Bleeding before the onset of pubertal development deserves evaluation. It could result from local causes or from hormonal factors.[4][5] In children, it may be challenging to determine the source of bleeding, and "vaginal" bleeding may actually arise from the bladder or urethra, or from the rectum.[8]

Vaginal bleeding in the first week of life after birth is a common observation, and pediatricians typically discuss this with new mothers at the time of hospital discharge.[9][10] During childhood, other possible causes include the presence of a foreign body in the vagina, trauma (either accidental or non accidental, ie child sexual abuse or molestation), urethral prolapse, vaginal infection (vaginitis), vulvar ulcers, vulvar skin conditions such as lichen sclerosus, and rarely, a tumor (benign or malignant vaginal tumors, or hormone-producing ovarian tumors). Hormonal causes include central precocious puberty, or peripheral precocious puberty (McCune-Albright syndrome), or primary hypothyroidism.

While the symptom is typically alarming to parents, most causes are benign, although sexual abuse or tumor are particularly important to exclude. An examination under anesthesia (EUA) may be necessary to exclude a vaginal foreign body or tumor, although instruments designed for office hysteroscopy can sometimes be used in children with topical anesthesia for office vaginoscopy, precluding the need for sedation or general anesthesia and operating room time.[11]

Premenopausal women

In premenopausal women, bleeding may occur as a result of a pregnancy complication, such as a spontaneous abortion, ectopic pregnancy, or abnormal growth of the placenta, even if the woman is not aware of the pregnancy.[12] This possibility must be kept in mind with regard to diagnosis and management. In addition, the possibility that the bleeding does not arise from the uterus itself must be kept in mind, and a gynecologic examination should be performed to look for vulvar or vaginal lesions, and cervical causes of bleeding such as cervicitis from an STI.[12]

The causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal women who are not pregnant have been classified using the FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) PALM-COEIN system.[13] This acronym stands for Polyp, Adenomyosis, Leiomyoma, Malignancy and Hyperplasia, Coagulopathy, Ovulatory Disorders, Endometrial Disorders, Iatrogenic Causes, and Not Classified. The FIGO Menstrual Disorders Group, with input from international experts, recommended a simplified description of abnormal bleeding that discarded imprecise terms such as menorrhagia, metrorrhagia, hypermenorrhea, and dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB) in favor of plain English descriptions of bleeding that describe the vaginal bleeding in terms of cycle regularity, frequency, duration, and volume.[14]

The PALM causes are related to uterine structural, anatomic, and histolopathologic causes that can be assessed with imaging techniques such as ultrasound or biopsy to view the histology of a lesion.[15]Endometrial polypsare benign growths that are typically detected during gynecologic ultrasonography and confirmed using saline infusion sonography or hysteroscopy, often in combination with an endometrial biopsyproviding histopathologic confirmation. Endocervical polyps are visible at the time of a gynecologic examination using a vaginal speculum, and can often be removed with a minor office procedure. Adenomyosis is a condition in which endometrial glands are present within the muscle of the uterus (myometrium), and the pathogenesis and mechanism by which it causes abnormal bleeding have been debated.[16] Uterine leiomyoma, commonly termed uterine fibroids, are common, and most fibroids are asymptomatic.[2] The presence of leiomyomas may not be the cause of abnormal bleeding, although fibroids that are submucosal in location are the most likely to cause abnormal bleeding.[15] The Malignancy and Hyperplasia category of the PALM-COEIN system includes malignancies of the genital tract, including cancers of the vulva, the vagina, the cervix, and the uterus. Endometrial hyperplasia, included in this PALM category of abnormal bleeding, is more common in women who are obese or who have a history of chronic anovulation. When endometrial hyperplasia is associated with atypical cells, it can progress to cancer or occur concurrently with it.[2] While endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial canceroccur most commonly among post-menopausal women, most women with endometrial cancer have abnormal bleeding, and thus the diagnosis must be considered in women during the reproductive years.[2][15]

The COEIN causes of abnormal bleeding are not related to structural causes.[15] Causes of abnormal bleeding, most commonly heavy menstrual bleeding, can be related to blood clotting disorders, or Coagulopathies.[17] Von Willebrand disease is the most common coagulopathy, and most women with von Willebrand disease have heavy menstrual bleeding.[17] Of women with heavy menstrual bleeding, up to 20% will have a bleeding disorder.[18] Heavy menstrual bleeding since menarche is a common symptom for women with bleeding disorders, and in retrospective studies, bleeding disorders have been found in up to 62% of adolescents with heavy menstrual bleeding.[19] Ovulatory dysfunction or anovulation is a common cause of abnormal bleeding that may lead to irregular and unpredictable bleeding, as well as variations in the amount of flow including heavy bleeding. Endocrine causes of ovulatory disorders include polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), thyroid disorders, hyperprolactinemia, obesity, eating disorders including anorexia nervosa or bulimia, or to an imbalance between exercise and caloric intake.

Endometrial causes of abnormal bleeding include infection of the endometrium, endometritis, which may occur after a miscarriage (spontaneous abortion) or a delivery, or may be related to a sexually-transmitted infection of the uterus, fallopian tubes or pelvis generally termed pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Other endometrial causes of abnormal bleeding may relate to the ways that the endometrium heals itself or develops blood vessels.[15] The most common Iatrogenic cause of abnormal bleeding relates to treatment with hormonal medications such as birth control pills, patches, rings, injections, implants, and intrauterine devices (IUDs). Hormone therapy for treatment of menopausal symptoms can also cause abnormal bleeding. Unscheduled bleeding that occurs during such hormonal treatment is termed "breakthrough bleeding" (BTB) Breakthrough bleeding may result from inconsistent use of hormonal treatment, although in the initial months after initiation of a method, it may occur even with perfect use, and may ultimately affect adherence to the medication regimen.[20] The risk of breakthrough bleeding with oral contraceptives is greater if pills are missed.[21] The Not Classified category of the PALM-COEIN system includes conditions that may be rare, or whose contribution to abnormal bleeding has not been well established or understood.[15]

Pregnant women

Vaginal bleeding occurs during 15-25% of first trimester pregnancies.[22] Of these, half go on to miscarry and half bring the fetus to term.[23] There are a number of causes including rupture of a small vein on the outer rim of the placenta. It can also herald a miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy, which is why urgent ultrasound is required to separate the two causes. Bleeding in early pregnancy may be a sign of a threatened or incomplete miscarriage.

In the second or third trimester a placenta previa (a placenta partially or completely overlying the cervix) may bleed quite severely. Placental abruption is often associated with uterine bleeding as well as uterine pain.[24]

Postmenopausal women

Endometrial atrophy, uterine fibroids, and endometrial cancer are common causes of postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. About 10% of cases are due to endometrial cancer.[25] Uterine fibroids are benign tumors made of muscle cells and other tissues located in and around the wall of the uterus.[26] Women with fibroids do not always have symptoms, but some experience vaginal bleeding between periods, pain during sex, and lower back pain.[27]

Diagnosis

The cause of the bleeding can often be discerned on the basis of the bleeding history, physical examination, and other medical tests as appropriate. The physical examination for evaluating vaginal bleeding typically includes visualization of the cervix with a speculum, a bimanual exam, and a rectovaginal exam. These are focused on finding the source of the bleeding and looking for any abnormalities that could cause bleeding. In addition, the abdomen is examined and palpated to ascertain if the bleeding is abdominal in origin. Typically a pregnancy test is performed as well.[28] If bleeding was excessive or prolonged, a CBC may be useful to check for anemia. Abnormal endometrium may have to be investigated by a hysteroscopy with a biopsy or a dilation and curettage.

In an emergency or acute setting, vaginal bleeding can lead to hypovolemia.[28] Postcoital bleeding is bleeding that occurs after sexual intercourse.

The treatment will be directed at the cause. Hormonal bleeding problems during the reproductive years, if bothersome to the woman, are frequently managed by use of combined oral contraceptive pills.

Postmenopausal bleeding

In postmenopausal bleeding, guidelines from the United States consider transvaginal ultrasonography to be an appropriate first-line procedure to identify which women are at higher risk of endometrial cancer. A cut-off threshold of 3 mm or less of endometrial thickness should be used for in women with postmenopausal bleeding in the following cases:

- Not having used hormone replacement therapy for a year or more

- Usage of continuous hormone replacement therapy consisting of both an estrogen and a progestogen

A cut-off threshold of 5 mm or less should be used for women on sequential hormone replacement therapy consisting both of an estrogen and a progestogen.

It the endometrial thickness equals the cut-off threshold or is thinner, and the ultrasonography is otherwise reassuring, no further action need be taken. Further investigations should be carried out if symptoms recur.

If the ultrasonography is not reassuring, hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy should be performed. The biopsy may be obtained either by curettage at the same time as inpatient or outpatient hysteroscopy, or by using an endometrium sampling device such as a pipelle which can practically be done directly after the ultrasonography.

FIGO classification

In 2011, the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) recognized two systems designed to aid research, education, and clinical care of women with abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) in the reproductive years.

Complications

Severe acute bleeding, such as caused by ectopic pregnancy and post-partum hemorrhage, leads to hypovolemia (the depletion of blood from the circulation), progressing to shock. This is a medical emergency and requires hospital attendance and intravenous fluids, usually followed by blood transfusion. Once the circulating volume has been restored, investigations are performed to identify the source of bleeding and address it.[28] Uncontrolled life-threatening bleeding may require uterine artery embolization (occlusion of the blood vessels supplying the uterus), laparotomy (surgical opening of the abdomen), occasionally leading to hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) as a last resort.

A possible complication from protracted vaginal blood loss is iron deficiency anemia, which can develop insidiously. Eliminating the cause will resolve the anemia, although some women require iron supplements or blood transfusions to improve the anemia.

References

- "Vaginal Bleeding | Uterine Fibroids | MedlinePlus". Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- Berek, Jonathan S.; Berek, Deborah L., eds. (2019). Berek & Novak's gynecology (16th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 9781496380333. OCLC 1064622014.

- Munro, Malcolm G (2014). "Investigation of Women with Postmenopausal Uterine Bleeding: Clinical Practice Recommendations". The Permanente Journal. 18 (1): 55–70. doi:10.7812/TPP/13-072. ISSN 1552-5767. PMC 3951032. PMID 24377427.

- Howell, Jennifer O.; Flowers, Deborah (2016). "Prepubertal Vaginal Bleeding: Etiology, Diagnostic Approach, and Management". Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 71 (4): 231–242. doi:10.1097/OGX.0000000000000290. ISSN 0029-7828. PMID 27065069.

- Dwiggins, Maggie; Gomez-Lobo, Veronica (2017). "Current review of prepubertal vaginal bleeding". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 29 (5): 322–327. doi:10.1097/GCO.0000000000000398. ISSN 1040-872X. PMID 28858895.

- Fraser, Ian S.; Critchley, H. O. D.; Munro, M. G.; Broder, M. (2007). "Can we achieve international agreement on terminologies and definitions used to describe abnormalities of menstrual bleeding?". Human Reproduction (Oxford, England). 22 (3): 635–643. doi:10.1093/humrep/del478. ISSN 0268-1161. PMID 17204526.

- Fraser, Ian S.; Critchley, Hilary O. D.; Munro, Malcolm G.; Broder, Michael; Writing Group for this Menstrual Agreement Process (2007). "A process designed to lead to international agreement on terminologies and definitions used to describe abnormalities of menstrual bleeding". Fertility and Sterility. 87 (3): 466–476. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.01.023. ISSN 1556-5653. PMID 17362717.

- Aprile, Anna; Ranzato, Cristina; Rizzotto, Melissa Rosa; Arseni, Alessia; Da Dalt, Liviana; Facchin, Paola (2011). ""Vaginal" bleeding in prepubertal age: A rare scaring riddle, a case of the urethral prolapse and review of the literature". Forensic Science International. 210 (1–3): e16–e20. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.04.017. PMID 21592695.

- Langan, R.C. (2006). "Discharge procedures for healthy newborns". Am Fam Physician. 73 (5): 849–52. PMID 16529093 – via PUBMED.

- "Patient Education: Newborn Appearance (The Basics)". UpToDate. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- Simms-Cendan, Judith (2018). "Examination of the pediatric adolescent patient". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 48: 3–13. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.08.005. ISSN 1532-1932. PMID 29056510.

- Berek, Jonathan S. (April 2019). Berek & Novak's gynecology. Berek, Jonathan S.,, Berek, Deborah L. (Sixteenth ed.). Philadelphia. ISBN 9781496380333. OCLC 1064622014.

- Munro, Malcolm G.; Critchley, Hilary O.D.; Fraser, Ian S. (2011). "The FIGO classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years". Fertility and Sterility. 95 (7): 2204–2208.e3. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.03.079. PMID 21496802.

- Fraser, Ian S.; Critchley, Hilary O. D.; Munro, Malcolm G.; Broder, Michael; Writing Group for this Menstrual Agreement Process (2007). "A process designed to lead to international agreement on terminologies and definitions used to describe abnormalities of menstrual bleeding". Fertility and Sterility. 87 (3): 466–476. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.01.023. ISSN 1556-5653. PMID 17362717.

- Munro, Malcolm G.; Critchley, Hilary O.D.; Fraser, Ian S. (2011). "The FIGO classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years". Fertility and Sterility. 95 (7): 2204–2208.e3. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.03.079. PMID 21496802.

- Abbott, Jason A. (2017). "Adenomyosis and Abnormal Uterine Bleeding (AUB-A)—Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management". Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 40: 68–81. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2016.09.006. PMID 27810281.

- James, Andra H.; Kouides, Peter A.; Abdul-Kadir, Rezan; Edlund, Mans; Federici, Augusto B.; Halimeh, Susan; Kamphuisen, Pieter W.; Konkle, Barbara A.; Martínez-Perez, Oscar (2009). "Von Willebrand disease and other bleeding disorders in women: consensus on diagnosis and management from an international expert panel". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 201 (1): 12.e1–12.e8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2009.04.024.

- Davies, Joanna; Kadir, Rezan A. (2017). "Heavy menstrual bleeding: An update on management". Thrombosis Research. 151: S70–S77. doi:10.1016/S0049-3848(17)30072-5. PMID 28262240.

- Zia, Ayesha; Rajpurkar, Madhvi (2016). "Challenges of diagnosing and managing the adolescent with heavy menstrual bleeding". Thrombosis Research. 143: 91–100. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2016.05.001. PMID 27208978.

- Rosenberg, Michael J.; Burnhill, Michael S.; Waugh, Michael S.; Grimes, David A.; Hillard, Paula J.A. (1995). "Compliance and oral contraceptives: A review". Contraception. 52 (3): 137–141. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(95)00161-3. ISSN 0010-7824. PMID 7587184.

- Talwar, P. P.; Dingfelder, J. R.; Ravenholt, R. T. (1977-05-26). "Increased risk of breakthrough bleeding when one oral-contraceptive tablet is missed". The New England Journal of Medicine. 296 (21): 1236–1237. doi:10.1056/NEJM197705262962122. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 854070.

- "Bleeding During Pregnancy - ACOG". www.acog.org. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- Snell, BJ (Nov–Dec 2009). "Assessment and management of bleeding in the first trimester of pregnancy". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 54 (6): 483–91. doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.08.007. PMID 19879521.

- "Placenta abruptio: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- Clarke MA, Long BJ, Del Mar Morillo A, Arbyn M, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Wentzensen N (September 2018). "Association of Endometrial Cancer Risk With Postmenopausal Bleeding in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Intern Med. 178 (9): 1210–1222. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2820. PMC 6142981. PMID 30083701.

- "Uterine Fibroids | Fibroids | MedlinePlus". Retrieved 2018-10-23.

- "What are the symptoms of uterine fibroids?". NICHD.NIH.gov. Retrieved 2018-10-23.

- Morrison, LJ; Spence, JM (2011). Vaginal Bleeding in the Nonpregnant Patient. Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. New York City: McGraw-Hill.